Bouncing Back: Resilience and Its Limits in Late-Age Composing

Louise Wetherbee Phelps—Old Dominion University

Keywords: aging literacy; late-age composing; resilience; lifespan writing; ecological lens; visualization

ABSTRACT

This essay is one of a series on my mother’s late-age composing, studying a writing project she started at age seventy and worked on for more than twenty-five years. Her intention was to integrate extensive reading, personal experience, and cultural observations to explain changes in parenting (and, by extension, education and enculturation of the next generation) from her childhood in the 1920s through the 2000s. When she died at 97, she left behind a 75-page draft, but was unable to complete her plans for revisions and an ending. I focus here on identifying the multiple factors in the ecology of her aging literacy that interacted to interrupt, slow down, and ultimately prevent her from finishing the essay. By studying her artifacts and documenting stresses on her literacy system (defined as body/mind/environment), I constructed timelines for her aging literacy and composing process, expressed in visualizations. These demonstrate a pattern of persistence and resilience, “bouncing back” from setbacks, but at progressively lower levels until she reaches the limits of her literacy system in late old age.

CONTENTS

When my mother, Virginia Wetherbee, died in 2015 at the age of almost 98, she left behind a body of lifespan writing, most of it unpublished. After her death I saved as many of her writings and composing materials as I could find. These records bore witness to a remarkable life of literacy that remained largely invisible to others, but was entangled with my own in countless ways from my earliest years to her death. My ideas about what I would do with this legacy were inchoate, but my first step—the “duty nearest me”—was to preserve it. . . tangible evidence of who she was as I had known her best, through our shared love of reading and writing.

My initial, vague thought was to memorialize her impact on my own writing in a brief, elegiac essay. But a year after her death, I took a huge leap and committed myself to a much bigger project: a retrospective lifespan study of the linked literacies and lives of my mother and me over 75 years, which I envisioned as a dialogic literacy memoir. My vision of the memoir is comprehensively dialogic: each chapter will develop different moments and aspects of our mother-daughter relationship, exploring the many literal and metaphoric patterns—“strange loops”—that bond us through literacy.[i]

My decision coincided with the first calls for studying writing across the lifespan and the formation of the Writing through the Lifespan Collaboration (see https://www.lifespanwriting.org/the-facts), followed by a series of publications on this goal (Bazerman et al., “Taking”; Prior, “Setting”; Bazerman, et al., Lifespan Development; Dippre and Phillips, Approaches)[i]. In this emerging work, “lifespan” (often coupled with “lifewide”) is a perspective that locates writing (“acts of inscribed meaning-making”) and writers’ development in time and history (see Dippre and Phillips’s working definition of lifespan writing research, “Generating” 6). This work frequently converges with multidisciplinary research and theories that conceive human beings as dynamic, active systems co-developing over time in relation to equally dynamic systems (biological, material, social, cultural) at many scales and levels from genes to the cosmos. As I will unfold here, this ecosystemic, chronotopic understanding of persons as a fusion of individual and context (person<>context) constitutes a world view with profound implications for how I conduct my own lifespan research.

Although this perspective can inform any research method and enrich studies of any age or period of literacy lives, longitudinal studies are valuable to expand the time span of scholarship in literacy development. Until recently these have been rare, limited in duration, and largely focused on college students. Given the methodological obstacles to undertaking prospective studies of individuals’ literacy development over the entire lifespan (Bazerman, “Lifespan Longitudinal”), scholars like Rebecca Williams Mlynarczyk have begun studying lifespan literacy lives retrospectively, in her case by interviewing four women in their eighties and nineties. It is likely that writing researchers will use their own lives as material for such studies, as retiring generations write autobiographical or autoethnographic accounts and memoirs.

My project joins in this emerging tradition of retrospective lifespan studies but—as a dialogic study of two writers developing interdependently over long lives—it is unique in several respects. Focusing on literacy lives in relation, reflecting the life-course principle of “linked lives,” is a recent trend (Brandt, “Writing” and Literacy; Rosenberg; Dippre). My project is a cross-generational study of a mother-daughter pair, of which one—myself—is both researcher and participant. But, as a lifespan study of a dialogic pair, mine will be unprecedented in the time span it covers: my mother, Virginia, lived (and wrote) for almost a century; the overlap in our literacy lives is seventy-five years. Whereas I am an academic writer and scholar of writing, literacy, composition, and rhetoric, still writing at eighty-two, Virginia (who shared these intellectual interests) composed for nonacademic audiences in genres like memoir and personal essay, drawing on wide reading of both scholarly and literary genres.[ii] After decades of shifting roles and relations in our close literacy partnership and dialogue, she counted on me to support her aging literacy in her final years and to steward her writings after her death.

Taken together, these facts presented a formidable challenge to my project on multiple levels: as a researcher, challenges of method, including data collection and positionality; as a writer, challenges of genre; as a person, challenges of grief, responsibility, and learning under the condition and unpredictable trajectory of my own aging. With little idea how even to start such a daunting task, I remembered the Quaker saying my mother quoted whenever I was stuck and didn’t know how to make a choice or move forward: “Proceed as way opens.” This article is the first—unexpected—fruit of following that advice. In it, I will trace the trajectory of my mother’s aging literacy—conceived through an ecodevelopmental lens as “the dynamic of her literacy system in late age”—and her slow composing as she worked on her final project, an unfinished essay on parenting.

I

The first core tasks I set for myself were to archive the writings of my mother and myself and to develop chronotypes (charts of time and place) for each so that I could ultimately align them to investigate and document the multiple levels in which our literacies were in dialogue (both intertextually and in our ongoing discussions of rhetoric, literate processes, learning, and texts). I have completed these tasks for Virginia’s writings; my own (a much larger oeuvre) are largely archived but not yet mapped chronotopically.

Among the materials I brought home with me after my mother’s death were drafts and notes documenting the long trajectory of her last project, a study of parenting that spanned cultural changes from her childhood in the 1920s to the present. She began researching this essay at age seventy and worked on it for more than twenty-five years. In 2010, when she was ninety-three, I typed up what turned out to be her last draft of Parenting—about seventy-five pages.[iii] Despite increasing frailty, my mother persevered in composing it for several more years, but in late age time outran her ability to complete her plans.

Having archived and read through my mother’s lifespan writings, close study of this unfinished essay was a natural starting point for my project. Uniquely among her writings, its incompleteness and extended composing trajectory meant that many of the raw materials of her composing were still available for me to collect and study. During her last few years, after following its progress through years of ongoing dialogue over our writings, I had become actively engaged in enabling her work on the essay. I was deeply invested in her task, saddened by its incompletion. As I reread and thought about this work as a testament to her continuing development as a writer in late age, I had many unanswered questions: what it meant to her, why she worked on it so long, how she planned to revise and end it, what kept her from finishing it.

My project made its first unexpected turn when my research on Virginia’s late-life composing took on a life of its own, generating questions and insights that transformed the project into an open-ended journey of discovery with many levels, paths, and possible outcomes besides the memoir. In this essay I begin to follow out those directions and adumbrate their richness.

My questions about Virginia’s unfinished essay opened my way to a deep exploration of aging and its relations to literacy and composing. Studying writing over the lifespan introduces “age” as a hitherto disregarded identity category and directs attention to “aging” as a necessary dimension of analysis for any literacy study (Bowen, “Composing”). Although not confined to older people, the intersection of age studies with literacy, writing, and rhetoric studies has generated a growing body of work on literacies and writings of old age, including “how literate activity shapes, and is shaped by, ideologies of aging” (vii). (See, for example, Bowen, “Beyond Repair” and “Age Identity”; Rumsey; Crow; Ray, Beyond Nostalgia; and the special issue Composing a Further Life). As I pursued my own inquiries and began to participate in this research community (Phelps, “Horizons”), I saw the potential for my study of Virginia’s aging literacy to contribute to this work.

To guide this study, I formulated two sets of research questions, which will be addressed in separate essays:

1. What was Viginia’s purpose in writing this essay? How did she define her composing task? What was the meaning of the essay to her, as the final piece in her writing over the lifespan?

2. Why was she unable to finish this essay despite working on it well into her nineties? What were the obstacles and constraints that affected her composing? How are these related to aging, especially in the later stages of adulthood?

These questions may seem merely personal and idiosyncratic to one woman, but they are rich in possibilities for revealing experiences shared among others as well as emphasizing the ineluctable individuality of each person’s lifespan writing experiences. The first set of questions has some precedent in a long multidisciplinary tradition of studying life review and reminiscence, especially at the end of life, in relation to wisdom. The second is largely unexplored, although even critical scholars who emphasize the ideological construction of old age have begun to acknowledge the role of embodiment and attend to how late-life frailties and losses affect the ecology of body, mind, and environment (Morell; Teems; Rumsey). In fact, my findings on the limits that affect resilience in aging literacy speak to these questions posed by Lauren Marshall Bowen as points of departure for future research:

How might bodily aging motivate, as well as render difficult (perhaps even impossible), particular engagements with literacy?

What might we learn about the literate identities of late-life writers who. . . have reduced autonomy over their own space? Or those who know longer have physical access to autotopographies when forced by financial and/or health [sic] to leave familiar home places? (“Age Identity”)

Counterintuitively, I turned first to the question of incompletion, perhaps because I was haunted by recent, vivid memories of my mother’s fading literacy at the end of her life; perhaps because of the parallels that made me wonder and worry about my own aging trajectory as I embarked on my own ambitious, long-term project in late life. It is that question which I take up in this essay, after a brief overview of the relationships between my questions and their possible answers.[iv]

II

The two sets of research questions I posed about my mother’s unfinished essay together represent positive and negative poles of aging as it affects literacy:

In terms of benefits, individuals’ development continues to the very end of life, enabling them—like my mother in this project—to seek the integrative, affective, and spiritual understandings and commitments we call wisdom (Cohen; Edmondson; Hoare; Kail and Cavanaugh; Karelitz, Jarvin, and Sternberg).

In terms of challenges, over time the fact and circumstances of aging ultimately erode the integrity of the system of body/mind/environment as it constitutes and supports literacy (Agronin; Bjorklund; Gawande; Gutchess; Harada, Love, and Triebel).

Although it is the interplay between these two poles that defines the trajectory of my mother’s literacy, this essay centers on how aging impacts Virginia’s literacy system to slow, disrupt, or impede her composing activities, rather than on the forces that fuel her resilience. I’ll locate my answers in the relationship between the composing task she set herself and her aging literacy, understood ecologically, in terms of interconnected changes in her brain, body, and environment. In tracing the timelines of her aging literacy and her composing I identified a pattern in which the forces of disruption and disintegration are repeatedly beaten back, but eventually overcome her resilience in very late old age. I call this resilience “bouncing back,” a term invented by American prisoners of war in North Vietnam to inspire one another’s recovery from being “broken” by torture and privation.[v]

What was Virginia’s composing task?

Her unfinished essay is on parenting—“the process that begins the shaping of a human being”[vi]—as it evolved in the US through periods of cultural change during her lifetime. The task she set for herself was to follow these changes from her own childhood to the present day, drawing on personal experience, cultural knowledge, and eclectic reading of academic and literary genres to explain how and why theories of human development and American practices of parenting had changed, and to arrive at an answer to what I would call her research questions: “How can parents give a child a sense of wonder? . . . A sense of place? . . . A set of values and principles? A sense of meaning in life conducive to future happiness? . . . How good is the “good enough mother”?[vii] the good enough father? What do good enough parents do?” (Virginia Wetherbee, Parenting). As I’ll describe in the companion piece to this essay, this effort to integrate knowledge from life experience, cultural observations, reading, and other semiotic sources represents a developmental literacy task characteristic of late age.

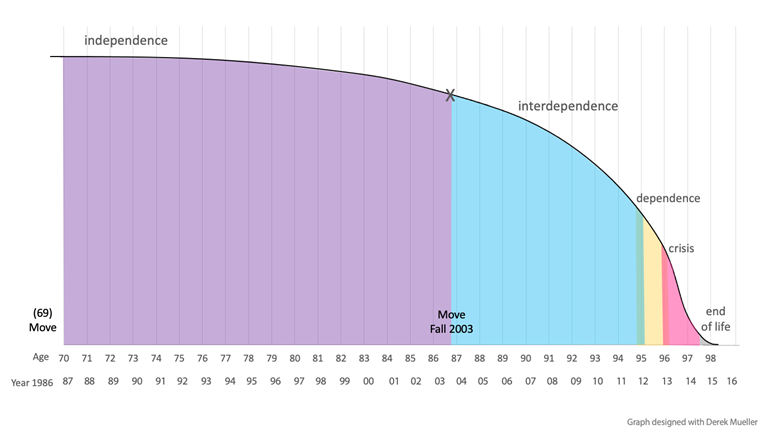

Virginia’s composing task grew larger and more complex as the “present” advanced, adding more years of sociocultural change to account for, while her lived experience and prodigious reading kept expanding and reconfiguring the knowledge she was integrating in the essay. Meanwhile technologies of literacy were evolving at an accelerating pace, adding new affordances for her research and writing, but also becoming more challenging to learn and use as she aged from seventy to almost ninety-eight. During those years Virginia transitioned from vigorous old age to “frail old age,” moving from independence to interdependence to dependence to crisis to end of life (Aronson). Her literacy aged along this timeline (both positively and negatively) as a function of interrelated changes in her body, mind, and environment. The positive side of her aging literacy is manifest in the composing project itself, and her sustained pursuit of it, but my focus here is on the forces of decline, the changes that ultimately set the limits to her resilience.

Although the complex relations that constitute the ecology of Virginia’s embodied literacy strike a balance between losses and gains as she matures, ultimately this balance breaks down in very late age, and, while she still composes—working at the task—the losses (the erosion of body, brain, and environment) are too great to finish it (Baltes).[viii]

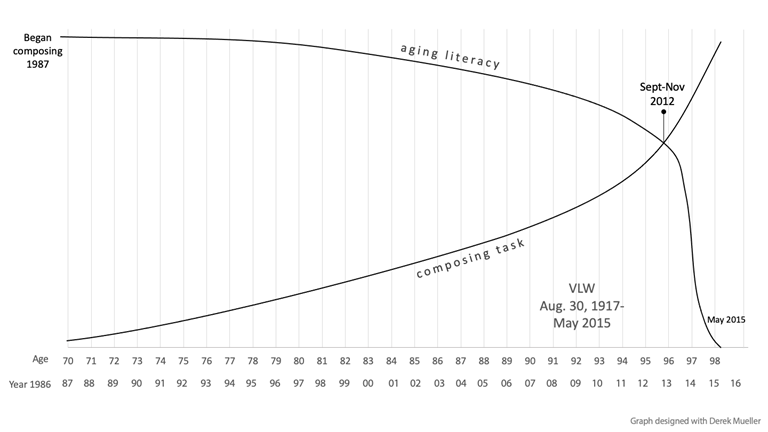

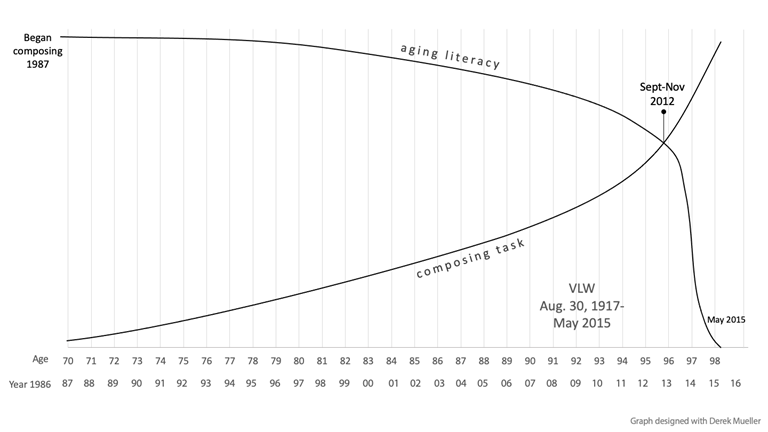

Figure 1 visualizes the relationship between Virginia’s composing task and her aging literacy over time as a relationship between a rising line—expressing the increasing scope and difficulty of the task she set for herself—and a falling line, which is a composite, abstract representation of her aging literacy.

Figure 1. Intersection of VLW's composing task and her aging literacy.

I propose that when these two lines cross, their intersection represents the moment when it became impossible to finish the essay: when Virginia could no longer bounce back to a literacy level sufficient to carry out her plan: to revise her drafts and compose new text for an ending. I set that date between September and November 2012, after her ninety-sixth birthday.

I explicate this figure and address my questions of incompletion and challenges to Virginia’s late-age literacy through a series of graphs that visualize my findings and claims.[ix] However, first I must take a step back to consider the methods that validate these findings and the conceptual framework that shaped them and makes them intelligible within the landscape of current research on aging, literacy, and lifespan writing development. Readers who are impatient to read the findings on Virginia’s aging literacy and composing trajectory as reported in the graphs—the heart of my essay—may want to jump forward to section VII (pp. xx), but ultimately those findings and their implications are only understandable in terms of an intellectual, affective, and methodological discovery process within the framework of the larger project.

III

At a meta-level, my research process for this project as a whole is governed by an overarching principle of emergence captured in my mother’s counsel to “proceed as way opens.” One consequence of adopting this principle is that the role of methods and theories in the project, and their complex interrelations, will not fit into any conventional description of methodology. The project requires an eclectic, hybrid approach to methods, research traditions, and theoretical lenses, adopting and adapting them to fit the purposes and objects of study in different parts or aspects of the whole.[x] These decisions can’t be anticipated, since they will emerge as I follow trails that turn, branch, and intertwine unpredictably.

As a process, proceeding as way opens requires me to keep my mind and heart open to new learning that constantly upends my understandings, both prospectively and retrospectively. In a long project—“slow scholarship,” “slow composing”—with many dimensions and threads, any apparent closure, like capturing some part of it in writing, is provisional and subject to revision. Accepting that feature as intrinsic to my research process, I’ve chosen to frame this essay as a journey of discovery and to make transparent certain moments when new information or insights serendipitously disrupted its trajectory.

My positionality in this project adds another, deeper dimension to my journey, one that manifested most fully while composing and recomposing this essay, at the nexus of method and genre. I found words for my experience (and many resonances) in the work of Jessica Restaino and Ruth E. Ray, two feminist scholars of literacy and rhetoric who have written dialogically about intimate others in parallel circumstances of illness and death, loss, love, and grief. In Surrender, Restaino researched and wrote about (and with) a beloved friend, during and after her friend’s illness and death from breast cancer. In her memoir Endnotes, Ray wrote about her loving relationship with a much older man with Parkinson’s disease, whom she met in a nursing home while doing research on aging. I write as a daughter about her mother’s late-age composing after a life-long literacy partnership, acting now as loving caretaker of her writing in the wake of her death. Their writings align my work with that of feminist scholars (in rhetoric, literacy, gerontology) on illness, death, and old age. In each case, we are learning by trial and error how to engage in what Ray calls “passionate scholarship,” which is “heartfelt and emotional but also intellectually rigorous and well-documented” (Endnotes 1). Ray and Restaino together eloquently capture the demands this kind of scholarship makes on us intellectually and emotionally, “collaps[ing]” walls between the personal, the academic, and the analytic” (Restaino 9). Our intimate relations to our subjects as witnesses and participants in their experiences—their/our stories—requires us to let go of (“unlearn”) the certainties of method and genre in what Restaino comprehensively calls “surrender as method.”

Restaino borrows the language of performance artist Nao Bustamente to express the same principle I called “proceed as way open”: “’The work that I do is about not knowing the equipment, and not knowing that particular balance, and then finding it as I go’” (Bustamente in Halberstom (interview) 143, qtd. by Restaino 65). Restaino interprets Bustamente’s words “as a method both for grief and for research and writing along the fault lines of illness, intimacy, and loss. Ultimately if we embrace Bustamante’s ‘finding it as we go,’ we become new agents and new researchers, over and over again for as long as we move through the work” (68).

As both scholars note, one of the great challenges of engaging in passionate scholarship is finding ways to write it: learning to blend, blur, or invent genres to capture not only its methodological features (flexibility, unpredictability, playfulness, hybridity) but its affective and ethical dimensions. That includes accounting for the experience of the scholar not only as observer-recorder-participant with an emotional investment in another’s life but also as a writer immersed in the processes of researching and composing as discovery and self-transformation. Writing this essay involved experimenting with ways to strike the right balance between personal and professional, different from what it will be in a memoir; making visible how discoveries are emergent in the intertwining of research and writing processes. The resulting blurred or hybrid genre, as I’ve noted, is most fundamentally a journey narrative. It constitutes a layered story of learning at several levels, each with its own surprises, obstacles and constraints, tradeoffs, and disruptions. One is a methodological journey of many facets that can’t be separated from genre. (As Restaino found, surrendering to a project like this means “breaking” methods and “destabilizing” genres). One is an intellectual journey of learning about the trajectory of Virginia’s own final journey as a persistent (slow) composer challenged by her aging literacy. And one is a journey of feeling, which saturates, complicates, and potentiates the others even when largely tacit.[xi]

IV

The nature of a project conducted in the time frame of “slow composing” means that what I have to say here about specific methods depends tacitly on the larger body of data, knowledge bases, and conceptual constructs I am building for the project, not just those that are named or cited in this essay. But I can foreground the most explicit research practices and knowledges that played a significant role in the claims and insights presented here. They depend, first, on empirically reconstructing timelines: for my mother’s life and literacy during the decades she worked on Parenting and for her composing process. For the late-life timeline, I selected from multiple streams of data I was gathering, studying, integrating, and triangulating for biographical/autobiographical purposes, attending to some types or parts specific to this period of her life. Sources I tapped for information included (not exhaustively) photos, correspondence, emails, packing lists, calendars, family documents and records, medical information and records, personal communication with family and friends, and writings by family members. I wrote journals to recapture my own memories and consulted family members about theirs. For her composing process, I gathered (and archived) materials like drafts, notebooks, outlines, reading notes, saved articles and poems, quotations, any kinds of notes (scraps, post-its), files—most of these undated and many of them partial, jumbled, and disorganized. I used visualization (diagrams, charts, drawings) to date, correlate, and record this information as timelines and to serve as a discovery process for their meaning. At first just heuristics for myself, as I charted relations through an ecological lens, my visualizations became a hermeneutical tool to discern patterns in the data and, ultimately, to embody and communicate their discovered meanings.

I want to comment on the quality of the evidence that allows me to construct these timelines with some confidence as to their meaning and its bearing on my research question. Given the complexity of an ecology, it’s impossible to identify all the interdependent forces and factors that contributed to Virginia’s aging literacy and composing potential. So the question is, how can I confidently discern patterns in data that is necessarily incomplete?

Setting aside the fact that in both principle and practice no one could give a comprehensive account, I do want to acknowledge circumstances and conditions that limited the data I could gather. First, this is a retrospective study. During the period of Virginia’s life I’m examining, my relationship to her was as a daughter, not researcher; I decided to undertake this project only after her death. I didn’t, therefore, make systematic observations, collect documents (until after she died), or interview her—as I now wish I could—to deepen my understanding of how she perceived her life events and literacy activities.

Second, I lived in close proximity to my mother sporadically, depending on our geographical locations, work and travel schedules, and (in later years) her needs for caregiving. During the early years of her writing Parenting I spent one sabbatical semester living with my parents, but otherwise visited on holidays and kept in touch by phone. After they moved into their son’s home (2003), we continued our holiday visits and, after retiring in 2009, my husband and I became part of the family network of caregivers. As my work and our own health permitted, we made short, frequent visits and brought her to visit us for up to two weeks at a time.

A further challenge is that I’m not a natural observer and have always had a poor memory for the detail of places, events, dates, and conversations. For these reasons I’ve drawn my data (direct and inferred) about Virginia’s late life as much as possible from concrete contemporaneous sources like emails, photos, calendars, notes, and various other kinds of documentation, including her own and family writings, using various clues to date them. I tried to check memories—my own and others—by triangulating them against one another and other evidence. In the case of her composing process for Parenting I have some of the same limitations in terms of direct observation, but a great deal of material evidence.

Despite these limitations, in tracing her aging literacy and her composing process over time, I have some incomparable advantages as Virginia’s daughter, literacy partner, and part of the family’s caregiving network in her later years. In the latter capacity, I helped with everything from medical care to shopping and followed her emotional well-being through frequent calls, emails, texts, and our visits. After her move in 2003 and increasingly as she aged, I became literally part of her extended, distributed literacy system. As such, I recognize obstacles, disruptors, or constraints as well as affordances and resources (many of them provided by me) for my mother’s aging literacy. Because of our deep bonds and the continual interweaving of our lives, I can interpret and extrapolate from incomplete, scattered data to discern patterns that no one else could. I am in a unique position to bear witness to the transitions and transformations that shaped my mother’s life trajectory during the period of composing her last essay.

V

In trying to understand why Virginia was unable to complete her last essay in late age, I realized that many, by default, would assume the simplest, most obvious explanation is dementia.[xii] But I instinctively resisted this way of accounting for the complexity of her aging literacy. It didn’t match my own observations of her literate capabilities up to very late in life, and I was suspicious that this label is applied too loosely to aging patients without medical studies to support diagnosis of an underlying disease. As Louise Aronson suggests (56), in popular use (and even for many doctors) it serves as a metaphor for old age, encouraging a dismissive view of older adults’ mental and emotional life, and even of their physical complaints. (Despite Virginia’s fortunate circumstances and strong family support, I observed how unconscious cultural stereotypes and assumptions about aging made some medical providers inattentive to her needs and poor listeners to her self-reported problems). I was also concerned that the term attributes behaviors solely to changes in the brain in isolation from body and environment, failing to acknowledge complex interactions and reciprocal relationships among them.

But because both doctors and family members assumed Virginia had dementia (presumably Alzheimer’s), I felt I had to consider seriously whether and how such a diagnosis might help me answer my question as to why she didn’t finish a composing task that obviously meant so much to her, and in which she persisted to a very late age. So I sought out characterizations (scientific and narrative) of dementia from multiple perspectives: nurses, doctors, neuroscientists, psychologists, advocacy groups, caregivers and family members, dementia patients themselves. I read compelling critiques of the concept, treatment by the medical community, and cultural attitudes toward it; and current expert views on dementia (and cognitive aging, in general). My overall impression echoed one of my mother’s favorite maxims, as illustrated in Figure 2: “It’s not as simple as you think.”[xiii]

Figure 2. “It's not as simple as you think.”

Since the 1980s, when Thomas Kitwood’s person-centered approach revolutionized thinking about dementia and its care, studies of dementia have advanced and complicated understandings of it from three broad perspectives, currently brought together in “holistic” views: biomedical, psychological, and critical gerontological. There are still ambiguities in distinguishing between normal cognitive aging and cognitive decline due to neuropathologies. The symptoms and conditions that define dementia as a clinical syndrome can manifest for many reasons other than a neurogenerative disease—infections, nutritional deficiencies, side effects of medications, depression. It is also recognized that biological, psychological, sociocultural, and other environmental factors interact with changes in the brain or nervous system to affect mentation. I had no way of knowing in Virginia’s case whether, how, and especially when her age-related changes added up to a technical diagnosis of “dementia.”[xiv]

But I chose not to label my mother’s aging as dementia for reasons that go beyond uncertainty about the diagnosis. First, it’s a blunt instrument for answering my questions about her aging literacy. It doesn’t tell me what she could and couldn’t do, why, or when, especially in relationship to other internal and external influences that I might be able to identify. Second, I believe that any diagnosis of dementia would apply only after late 2012, when (as explained below), I place the moment that she became unable to complete the essay, although her composing efforts continued beyond that point. Up to that time, I have evidence that her literacy abilities (viewed as a system) were intact, although not able, in Marc E. Agronin’s words (writing about Erik Erikson at the end of his life), “to participate verbally and intellectually at the high level of discourse and writing” (78) she had enjoyed at her peak. So, instead of medicalizing my mother’s aging literacy, I take my cue from Reeve Lindbergh’s writing about her mother Anne Lindbergh when she chooses phenomenological over medical language to describe her mother’s late life after several strokes. I chose to observe (retrospectively) and document in as much detail as possible the ways that brain, body, and environment were coactive in my mother’s literacy aging and resilience.

Beyond the reasons given, this approach reflects a long-held philosophical stance—contextualist and dialogic—that grounds an ecological perspective on human life and development (Phelps, Composition). In contrast to largely brain-based ways of construing aging, I view the person, her development, and her literacy ecosystemically: which is to say, as an embodied, distributed system of multicausal, reciprocal relations among brain, body, and environment (Bronfenbrenner; Overton, and Molenaar). This conceptual framework profoundly influenced the way I searched for, named, perceived, and valued data about Virginia’s aging literacy: more specifically, how I came to visualize it in ways that became themselves findings and interpretations. It is essential to understanding what I believe this data means.

To explain in what sense my conceptual framework is “ecological,” I need to situate it comparatively within the current landscape of ecological scholarship in rhetoric and composition. While I have affinities with this work and share many of its theoretical influences, my ecological approach has been shaped for different objects of study, by a network of sources suited to my purposes. For the same reasons, the following synthesis of ecodevelopmental principles may be productive for other scholars who need theories that afford lifespan research on writers, their writings, and their literacy and rhetorical development.

VI

As Laurie Gries observes, ecological views are now ubiquitous in studies of rhetoric and writing:

Since the 1980s, ecology has gained much capital as a metaphor and a model in the study of rhetoric and writing. Ecology is predicated on the belief that biological and social worlds are jointly composed of dynamic networks of organisms and environments that exist on multiple scales and are interdependent, diverse, and responsive to feedback. In simplest terms, to consider something as ecological is to recognize its vital implication in networked systems of relations (Bennett, Syverson). In less simple terms, thinking ecologically acknowledges the dynamic complexity of these networked systems, the interrelated, laminated layers of activities that constitute them, and the mutual transformation that occurs among intertwined elements. (67)

As Gries acknowledges, applications of ecological thinking in the field of rhetoric and composition/writing studies are quite diverse, both in terms of what scholars hope to characterize or explain (their objects of study) and in the theories they invoke and borrow from to theorize these phenomena (systems). So, for example, contributors to the collection in which Gries’s comments appear (Dobrin, Writing) focus on either “writing” or “rhetoric” as a system or ecology. As explained in the editor’s introduction, this work springs from “a convergence between complex ecologies, writing studies, and new-media/post-media. In this convergence, network theories, systems theories, complex ecologies, and posthumanist theories emerge as paramount in the shaping of writing theory” (Dobrin, “Ecology” 2). These scholars see their work as motivated by the complexities added to writing (or rhetoric) as systems by digital and new media technologies that have transformed “the invention, production, circulation, remix, and recirculation of writing” (7). Still other scholars have sought to “think ecologically” about writing programs (Cox, Galin, and Melzer; Phelps, “Between Smoke”; Reiff, Bawarshi, Ballif, and Weisser).[xv]

Hannah Rule, in forwarding a “situated” theory of writing processes that emphasizes their physical, material qualities as an immediate, embodied and emplaced experience, argues that many contemporary theories influencing rhetoric and composition/writing studies (post-process, new materialist, post-humanist, cultural-historical activity, actor-network), especially when identified as “ecological,” tend to “zoom out” to macro-scales in characterizing the situatedness of writing activity (49–70). In doing so they can decenter or elide human subjects and their agency as well as “preclude. . . the study of writing’s radically local physical-material situations,” what she calls the micro-view (54). Certainly, this is the case with many ecological views of writing and rhetoric, since they take the system at its widest possible reach as their subject: in John Tinnell’s language, they seek a position or methodology “with which we may discuss writing as an ecological phenomenon without recourse to individualized entities such as writer, reader, text, etc.” (130).

I value the macro-studies of writing, literacy, and rhetoric ecologies, including the way they and the theories they draw on have expanded and transformed notions of agency. However, to think ecologically doesn’t require limiting our objects of study to the macro-scale, nor does focusing on persons as objects of ecological study limit us to the micro-scale, since human beings are themselves self-organizing systems, which are constituted and experienced in and across multiple time scales. (Rule makes this point herself, arguing for a “modulation or continuum of focus on micro- and macro-situated forces” [(62] whose dynamic is revealed in studying the composing moment.) In fact, human development has been studied for decades from an ecological perspective. My particular interest is the scale of the life span, and the theories I’ve sought out are those that help me study persons and their literacies as they develop over long spans of time. In the case of the current study, that is my mother Virginia’s literacy over several decades, but in my memoir it will be a dyad, mother and daughter, over shared lifetimes linked by literacy experiences, texts, reciprocal learning, and dialogue. Developmental theories provide the center for a network of theories that help bring ecological perspectives to these goals and objects of study.

My own lifetime work as a scholar has deep roots in studies of human development, which have evolved radically (as a multidisciplinary enterprise) since I first encountered them more than 40 years ago in the philosophical context of contextualism.[xvi] In addition, recent attention to lifespan studies of writing and literacy has provided a new context for ecodevelopmental perspectives to flourish within the field (Bazerman et al., Lifespan Development; Dieppe and Phillips, Approaches; Driscoll and Zhang; Smith and Prior; Pinkert and Bowen; Roozen and Erikson). What I’d like to do here is to lay out, without detailing all the scholarship that contributes to my view, some major principles that provide affordances for my own project. In doing so, it will be clear how many features in ecodevelopmental theories echo the qualities attributed to ecological thinking in other regions of the field.

In preview, the principles I draw from these theories offer a rich conceptual framework for studying an individual ecologically: as embodied; as unique; as having agency (while understanding agency as distributed); as a set of interpenetrating contexts (internal and external); as a system (of systems, within systems); as changing and developing over a lifetime. This framework affords description and analysis of a person’s literacy (and aging) as something not contained within an individual’s head (i.e., cognitive or brain-based) but fully embodied, material, sociocultural: constituted by a system of complex, changing interdependencies.

1. Developmental (bioecological or ecosystemic) theories are person-oriented, interested in studying how individuals develop over the lifespan. In Urie Bronfenbrenner’s mature Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) model for developmental research, the person is the “center of gravity” of the system, composed of 1) the developmental process, “involving the fused and dynamic relation of the individual and the context” (symbolized as person <> context); 2) the biopsychosocial, historical person; 3) the context, conceived as laminated systems or levels of an ecology (from immediate to remote environments); and time, understood as multiscalar (summarized by Lerner, “Urie” xv-xx).

2. The person is defined as an active organism engaging an active context, which enables a conception of human agency that is compatible with a distributed view of agency. In Willis F. Overton’s relational-developmental systems approach, “the system’s [person’s] development occurs through its own embodied activities and actions operating coactively in a lived world of physical and sociocultural objects, according to the principle of probabilistic epigenesis (12), [meaning that] “the role played by any part process of a relational developmental system—gene, cell, organ, organism, physical environment, culture—is a function of all of the interpenetrating and coacting part processes of the system” (52).

3. Developmental theories emphasize how these complex interdependencies, as they enter into an unfolding history of change over time, make each human being’s life trajectory and personhood unique. Tania Zittoun, Jaan Valsiner, Dankeert Vedeler, João Salgado, Miguel M. Gonçalves, and Dieter Ferring call this uniqueness an individual’s “melody of living” (1–2).

4. Ecodevelopmental theories participate in a broader base of scholarship that highlights time (its levels, scales, cycles, and rhythms) as an essential, profound, and complex aspect of human experience (Adam; Lemke; Thibault; Madsen, and Cowley).[xvii] Developmental science “emphasizes the dynamic interplay of processes across time frames, levels of analysis, and contexts. . . . Units of focus can be as short as milliseconds, seconds, and minutes, or as long as years, decades, and millennia. In this perspective, the phenomena of individual functioning are viewed at multiple levels—from the subsystems of genetics, neurobiology, and hormones to those of families, social networks, communities, and cultures” (Carolina Consortium on Development 1). It is very challenging to explain the role and relations among multiple time scales in human lives: how they are coordinated, negotiated, and experienced—subjectively and intersubjectively; how they operate interdependently in a given moment, over a lifespan, within historical cohorts, and across generations. This challenge has been a major theme of life course studies (Elder), including the principle of studying linked lives within and among generations (in literacy studies, see Brandt, Literacy; “Writing”; in writing studies, Elliot and Horning). In lifespan studies, Paul Prior has critiqued views that simplify and fix relations between micro and macro “structures,” often identified with vertically nested time scales; he argues for a much more complex temporality of becoming, wherein “a local moment participates in chronotopic flows” (“How Moments” 10).

It's not surprising that developmental studies would have to engage deeply with time within an ecological perspective, given the time frame of a lifetime as a starting point and the necessary extension of contexts in both time and space (as noted earlier, zooming out to larger and slower systems, as well as zooming in to the tiniest and fastest ones). One consequence has been the realization that the human being “is not definable at a single instance in time, but only over finite time-intervals, and in fact ultimately only as a trajectory entity [my emphasis] developing and individuating through its interactions with its environment over the whole lifespan course from conception to decay” (Lemke 283). Hence the emphasis on life and development as a process of “becoming” (Zittoun, Valsiner, Vedeler, Salgado, Gonçalves, and Ferring; in writing studies, the work of Prior and Roozen.)

5. Last, as demonstrated by Zittoun and her colleagues (a multidisciplinary group of European scholars), among others, developmental theories are hospitable to semiotic theories: indeed, these scholars argue for their integration to explain the uniqueness of human lives and developmental trajectories. They position their inquiry as beginning with two assumptions: “the irreversibility of time and the semiotic nature of making sense of our human experience,” requiring a dialogue between two theoretical traditions, a developmental science and a sociocultural psychology (12). These traditions define two complementary perspectives for developmental study, the more objective “outside” view of the natural scientist and the “inside” phenomenological or subjective (semiotically mediated) view. Ultimately this distinction is heuristic, since only together do they account for human development as a “dynamic unity” of mutually constitutive domains (32). This makes Zittoun and her colleagues’ particular version of developmental theory very congenial for a project studying literacy development and lifespan writing.

Some of the developmental premises I’ve named already are suggestive for how to conduct my own study, but I want to add a few others with methodological implications. First, the complexity of ecological reciprocities, interpenetrations, and coactions (terms that have replaced “interaction” in developmental science) and the concept of a living organism as an open system (nonlinear, adaptive, self-organizing, self-regulating) have led scholars to reject linear causality in favor of nonlinear systemic patterns of change (emergent, transformational). Instead of “causes” they identify functions like affordances, resources, or assets along with conditions, obstacles, disruptors, or constraints (Overton; Zittoun et al.).[ii] I adopt this language to analyze my mother’s aging literacy and answer my research questions here.

Second, the question arises, when you understand any phenomenon as fundamentally relational and systemic, how you can distinguish between a system and its environment? Zittoun and her colleagues acknowledge the dynamic wholeness of person and environment as a single system (often symbolized as person <> context), but agree with other scholars that we can define borders flexibly depending on what we are researching, and thus at what level or scale we define “the system” (e.g., a person, a dyad, a community) in distinction from its “environment” (Zittoun et al. 41–42). In addition, a given study may choose to focus on what Bronfenbrenner calls the “immediate environment” (the “microsystem”) or on relations to layers of the remote environment (as in Elder’s life course studies examining the impact on individuals and cohorts of growing up in different historical worlds).

Various considerations have led me in this part of my project to focus on my mother’s relations to her immediate environment, especially as it afforded or constrained her ability to complete her essay in late age.[xviii] To do this, I will at times draw the border between Virginia as organism (brain-body) and her physical, material, and sociocultural environment. At the same time, in attributing qualities to her life, activity, or experience, I always understand them relationally, as a nexus of forces—biological, neurological, interpersonal, sociocultural, material, spatiotemporal, and more. As Timo Järvilehto puts it regarding cognition, “‘All concepts referring to mental activity—like perception, emotion, memory, etc.—describe only different aspects of the organization and dynamics of the whole organism-environment system’” (330, qtd. in Steffenson and Pederson 95).

Within this framework, then,“aging literacy” refers here to the dynamic of my mother’s literacy system in late age, understood as historically formed habits, skills, and knowledge (assets) coupled with contextual affordances and constraints, all subject to complex, interdependent change over time. At any point on the timeline, the quality and accessibility of her coactive internal and external resources defines Virginia’s potential for continuing to engage in processes directed to her composing task.

VII

From the larger body of data I was collecting for the whole project, I selected and searched for further information about the ecology of my mother’s work on the unfinished essay, guided by an ecodevelopmental lens in trying to understand the dynamic of Virginia’s aging literacy system. Among other things, that lens directed my attention to timelines in her life and her slow composing, reflecting a lifespan framework that foregrounds change over time in all aspects of a writer’s ecology. Mapping these timelines not only provided representations of data, they revealed relationships that make sense of it. In effect, my graphs became findings that serve as their own interpretations. To introduce these maps and discuss their meanings, I return to Figure 1, displayed again below, which visualizes the relationship between Virginia’s composing task and her aging literacy over time as a relationship between a rising line—representing the increasing scope and complexity of her task—and a falling line, a composite, abstract representation of her aging literacy.

Figure 1 (reprinted). Intersection of VLW's composing task and her aging literacy.

I propose that the intersection the rising and falling lines mark the moment—between September and November 2012—when Virginia could no longer bounce back to a literacy level sufficient to carry out her plan.

The visualizations that follow represent interpretations of the falling line of aging literacy (as constituted by episodic changes and entropy), juxtaposed with a timeline of Virginia’s composing process for her unfinished essay.

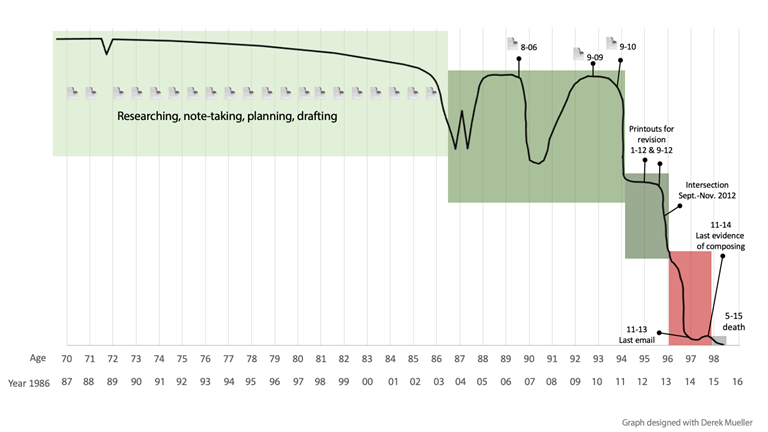

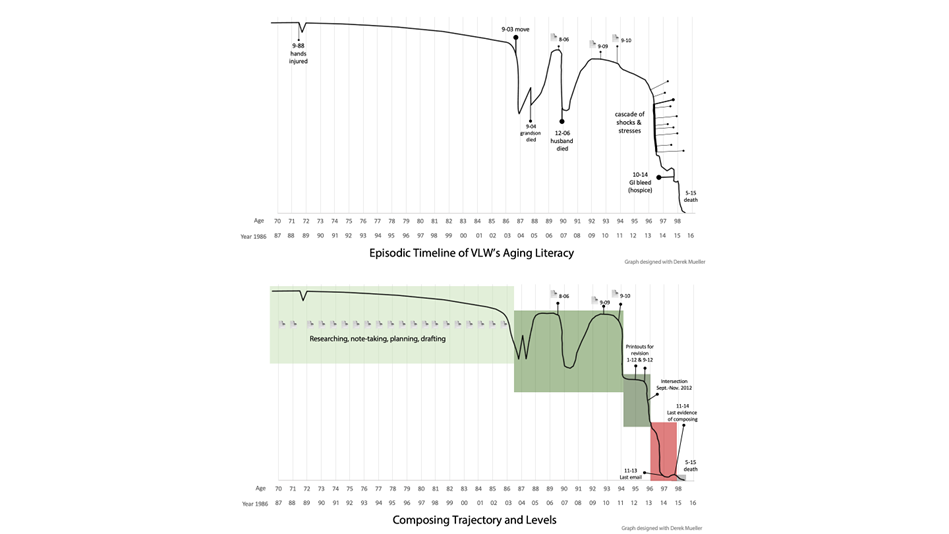

In Figures 3 and 4, I interpret the composite falling line of aging literacy in terms of two forces of decline: episodic changes, where a time-specific event or change in condition causes shocks and stresses to the system; and slower, indeterminate ones reflecting entropy in the system, like age-related decline in structures and functions of the brain and body, chronic health conditions, and environmental changes.

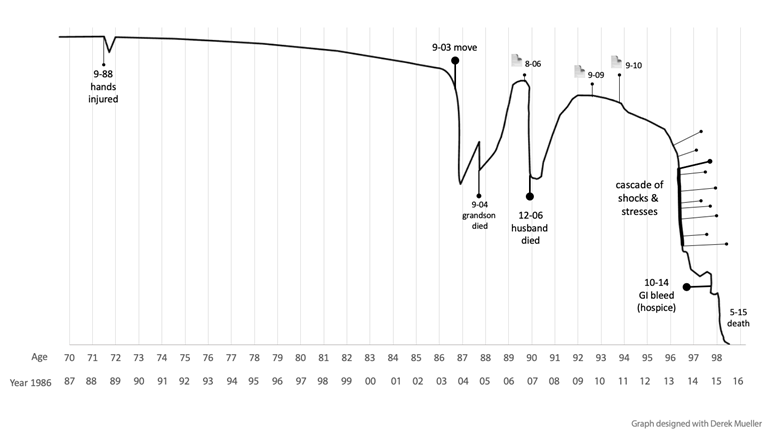

The episodic timeline (Figure 3) visualizes the pattern of “bouncing back” from shocks or stresses that disrupt my mother’s literacy.

Figure 3. Episodic timeline of VLW's aging literacy.

In constructing this timeline, it was impractical to visualize even all the data I do have about the time-specific stresses and shocks that acted as disruptors for Virginia’s literacy. Major examples (events with prolonged impact) that I documented fall into several categories: health (injuries and illness); relationships (absence, loss, or disconnection from loved persons, pets, and even objects); and relocation from her own home, a watershed moment for any older adult. These are exemplified in the timeline, but zooming in would reveal the strains and upsets that create ups and downs in every life from day to day, fluctuating in levels of intensity and duration. In frail old age, minor stresses may be magnified in their physical and emotional impact. Overall, such stresses impair literacy capability in multiple ways, from physical disability, cognitive loss, anxieties, and emotional distress to diminished control over one’s environment.

The graph in Figure 3 identifies selected instances where an event shocks or stresses Virginia’s literacy, shown as a dip or drop in the line. The line turns upward toward a higher literacy level (meaning more active and more productive) as she bounces back. How low it goes, and how fast she bounces back, depends on the severity of the shock; where she is on the timeline of aging; interaction with other stresses; and counterforces that strengthen resilience. Overall, the pattern resembles a bouncing ball that bounces back lower and lower each time until finally it runs out of energy.

In 1988, early in Virginia’s project, a tree fell on her car as she was driving and landed on her hands, causing loss of one finger and permanent damage to others. After several months of recovery she bounced back to her former high literacy level, reading at her usual pace and scope, typing (on an old Smith-Corona typewriter), working on the essay intensively throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. But in 2003 my parents gave up driving and moved from a large house with an extensive library and office into a compact suite of rooms in the home of my brother and his wife. Her literacy work was disrupted while she slowly reestablished a niche for reading and writing in their main living space, into which my brother had fitted a scaled-down version of the office—desks, computer, files, bookshelves—my parents had shared. Once settled in (with a fraction of her old library), she continued to expand her reading material (new books, daily newspapers, journals, and magazines, internet downloads) and restarted work on the essay.

The episodic timeline (figure 4) shows her bouncing back after two deeply affecting deaths—a grandson only a year later, in 2004, and her husband in late 2006, to resume her normal reading habits and produce drafts in 2006, 2009, and 2010. However, she became frailer in the next few years and starting in late 2012 experienced a cascade of physical, cognitive, and emotional stresses, including a serious illness lasting from April to August 2013. (This marks a difficult transitional period of increasing dependence, culminating in the need for professional caregivers.) After that, in late old age the dips turn into a steeper falling line, the bounce-backs diminishing, until the line flattens as she approaches end of life. After an uptick in health and literacy activity between June and October 2014 (which I attribute to a dedicated caregiver),[xix] a catastrophic internal bleed put her in hospice that October. Even then she recovered enough to bounce back a little, still reading as late as December.

Despite persistent bounce-backs, the overall declining pattern in her resilience reflects two facts. First, any event or condition that causes major stress has ripple effects and lasting consequences. Virginia had to cope the rest of her life with damaged fingers, the loss of loved ones, and the effects of her move in 2003, all impacting her literacy. In late old age, some health events become chronic, chronic conditions worsen, and stresses combine and cumulate to create cascades. The cascade that accelerated her decline included, for instance, episodes where frustration with malfunctioning technology (phones, computers) undermined her increasingly tenuous grasp on long-held skills she relied on to communicate. Accumulating health problems not only made her increasingly fragile but created stresses around the logistics of marshalling family help to monitor her needs and medications, make appointments, and transport her—in the case of her serious infection, to administer IV antibiotics at home.

Second, shadowing the episodic timeline and invisibly shaping its curve downward is the aging effect of entropy, initially slow, then accelerating, as different elements of the body-mind-environment system lose order and function. Figure 4 visualizes its gradual decline as a system capable of literate activity and, specifically, Virginia’s composing task.

Figure 4. Entropy of aging (VLW).

My assumption of decade-by-decade steady losses is oversimplified, as studies of aging differentiate numerous structures and functions, each aging at different rates and peaking at different ages, variable among individuals (Bjorklund; Gutchess; Harada, Love, and Triebel; Hartshorne and Germine). Further, the period of life after seventy-five or eighty is the least studied and the least well understood. But, since no one did clinical observations or diagnoses of all these changes, in assuming that entropy does take its slow toll on my mother, I’m recognizing that she was like all mortals subject to progressive physical and cognitive aging, although the composing evidence suggests that the sharp decline in abilities predicted by seventy-five or eighty happened as much as a decade later for her. The colors in figure 5 reflect my best estimate of her passage from independence to interdependence (sharply demarcated by the move in 2003) and then more indeterminate passages between interdependence and dependence in 2012 and between dependence and crisis in 2013.[xx]

I tried visualizing entropy of the body, brain, and environment in more detail, but gave up not only because of the complexity of tracing so many strands of change, but also because so much of it is either impossible to directly observe (neural changes) or so slow as to be imperceptible or very hard to date. But the signs accumulated that she was losing ground: her declining mobility, balance, and stamina; her recurrent efforts to relearn fading technology skills; her loss of prospective memory for future events; the deterioration in her workspace as more and more clippings, books, papers, and notes overflowed beyond her capacity to keep them organized. She knew it, and counted on me to help her preserve, restore, compensate, or adapt to these losses in her ecology (see Rumsey; Bowen, “Age Identity”). These gradual changes surfaced in my data as moments when I took steps to slow down or offset them: for example, balance exercises, a cane, calendar help, storage and memory aids. The inferences I was able to make from these clues guided me in determining the transitions from interdependence to dependence to crisis to end of life.

Figure 5 shows a composing trajectory for Virginia’s unfinished essay on parenting that I painstakingly reconstructed from evidence completely independent of how I established the episodic timeline:

Figure 5. Composing trajectory and levels (Parenting).

The dips here are pauses or disruptions of her composing; the highs represent active composing at some level. The colors distinguish four levels of composing differing in intensity, continuity, and type of product (from full drafts to clippings and saved quotes.)

You might wonder how I know when she was composing. To determine this, which depends on what counts as composing, I defined composing as “intention and attention” directed at her composing task, made evident in activity (mental, physical, material) I could observe or infer.[xxi] At level one, she was at her highest literacy level, giving intensive, sustained attention to her task over sixteen years of research, reading, notetaking, and drafting. At level two, after moving in 2003, she had significant disruptions and less control of a more constrained environment but was still able to continue reading (at the same pace) and (more slowly than at level one) researching, drafting new sections, and revising previous ones. At level three, in 2011 and 2012, her intention remained strong, and she worked persistently and productively at her task, although likely at a slower pace and in shorter micro-events of composing. In this period she gave sustained attention to revisions and replanning, materialized in a body of notes, outlines, and annotations on drafts, focused on the goal of finishing the essay. She continued her habits of mining reading and other sources for possible additions (new ideas, information, quotations, citations) to the essay. However, she could no longer muster the cognitive resources or sustained time and energy to execute these plans. In level four (2013-2014) she hadn’t given up her intention, although it was weakened (the clippings and quotations I found suggested her thoughts were turning to the circle of life and the prospect of death). But her attention to the composing task was very intermittent, brief, witnessed in scattered clippings, quotes, post-it notes, notecards, and stray pieces of paper with key words on them. Some articles saved in late 2014 are my last evidence of her intention and attention to composing the essay.

I was amazed to discover, as shown in figure 6, how closely her composing tracked the episodic timeline, showing the degree to which the stresses and shocks to the ecology of her aging literacy directly affected her composing trajectory. I’ve put the two graphs together to demonstrate how they follow the same bounce-back pattern:

Figure 6. Episodic timeline and composing trajectory in figures 4 and 5 compared.

The gradual slope of decline in the entropy diagram (see figure 4 above), moving from independence to interdependence to dependence to crisis, is echoed in the four levels of composing.

The mapping methods that proved so fruitful in this study looked at my mother’s aging literacy and late-life composing from what my co-author Derek Mueller calls the “middle altitude,” positioning the researcher’s gaze at a “middle distance” to “attend to patterned movement” that is not visible at the extremes of far away or close up (Mueller, Williams, Phelps, and Clary-Lemon 10). This language reflects a “networked methodological approach” introduced in our collaborative research on cross-border networks in writing studies (6–12). In defining this approach to studying a complex, interconnected phenomenon, we are tackling a problem that has been a major focus of early lifespan writing studies, whose scholars have repeatedly argued that the complexity and diversity of writing development (lifespan and lifewide) requires multi-disciplinary, multi-site study from a great range of methodological perspectives (Bazerman et al., Lifespan Development; Dippre and Phillips, Approaches). But historic “conflicts of method” among disciplinary and national research traditions pose the problem of how to achieve what Dippre and Phillips call an “actionable coherence” in the knowledges they produce. The networked methodological approach proposes that one way to do so is to frame relations among methods as complementary in terms of variations in scale (distance versus close) and scope or aperture (wide versus narrow) (Mueller, Williams, Phelps, and Clary-Lemon 9). (These variations can also implicate the range of time: see Lemke on time scales in research methods). Juxtaposing, coordinating, and interconnecting these scales and lenses, as we did in our collaboration studying cross-border networks, allowed us to align and integrate forms of knowledge at different distances.

The middle altitude of this study facilitated remarkable, surprising discoveries of longitudinal patterns over more than two decades of Virginia’s literacy life, but it needs to be complemented by ecological analyses at a more granular level. I plan such an analysis focusing on Virginia’s “writing habitat” (Alexis) after her transition to living in my brother’s home, zooming in to examine the evolving relations between her aging body-mind and changes in the material surround for her composing after the move. I’ll draw on methods exemplified by Cydney Alexis, Lauren Marshall Bowen (“Age Identity”; “Literacy Tours”), and other scholars of material culture who view cognition, literacy, and rhetorical practices as distributed within ecologies of human and non-human agents. In Virginia’s writing habitat, an assemblage of space and materials served as prostheses for her body-mind; one goal is to examine how changes in this material environment as resources for her literacy practices are interdependent and reciprocal with changes in her embodied cognition. But, beyond their practical functionality, new materialist scholars highlight humans’ deep emotional investments and identifications with objects they assemble around them and use over time. I will look at this changing landscape of “evocative objects” in my mother’s final writing habitat through the lens of Jennifer A. Gonzalez’s rich concept of an “autotopography”: for the writer, a “visual and tactile map” of a writing space populated with material objects and tools that have become imbued with feeling and personal meaning, expressing a writer’s identity through their affordance and participation in her embodied, affective experiences of composing (134).

VIII

VIII.

A serendipitous event (disrupting my journey late in writing this piece) subtly shifted my “sense of an ending”—to my mother’s life, to this essay—adding more dialogic threads to its texture. Reliving the details of her life in old age, handling the books and objects she surrounded herself with, hearing her voice in emails and composing notes, all attuned me acutely to her individuality: I listened to her distinctive melody of living. But by the time I wrote my first version of an ending, I was struck by how her story resonated with others’ experiences of old age, recounted in studies and narratives I had read: now I saw in her life universal dimensions in the human experience of aging. Then a chance event—watching a webinar on healthy cognitive aging—threw new light on this gestalt shift and indeed on everything I had observed and visualized in my mother’s aging. I could no longer end my essay at that moment in my journey: I had to write an ending to share this discovery and the way it refigured the intellectual and emotional dynamics of the essay.

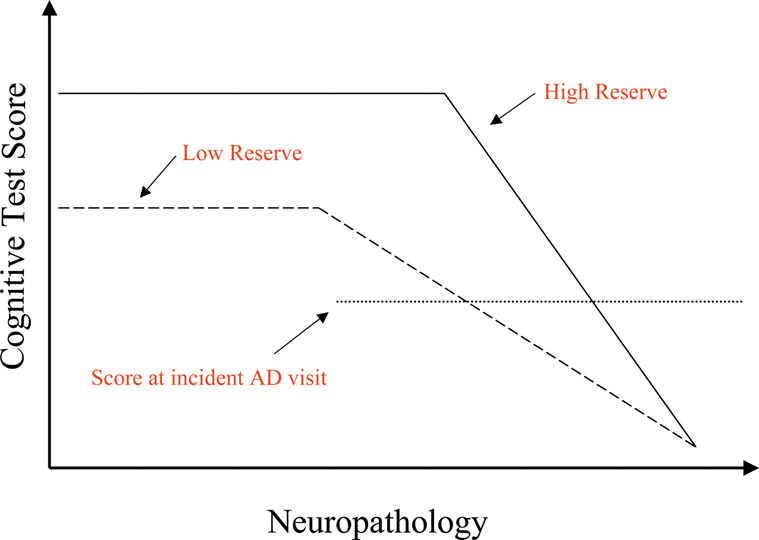

Fittingly, insight came in an iconic form. In her webinar Quinn Kennedy presented this diagram (figure 7), comparing two hypothetical individuals in terms of their “cognitive reserve,” to explain the variability in people’s experiences of cognitive decline:[xxii]

Figure 7. Variability in cognitive reserve (Stern 2012).

Kennedy explained that in research on cognitive aging “cognitive reserve” refers to how efficiently and flexibly you use your brain, helping to compensate for the age-related accumulation of neurodegenerative changes in the brain (Stern; Tucker and Stern; Resilience Workgroup). Having high cognitive reserve maximizes individuals’ cognitive potential over the lifespan; it slows or delays the onset of cognitive decline, reduces the risk of dementia, and may even prevent neuropathologies. Kennedy went on to summarize substantial evidence that, even as older adults, we can preserve healthy brain function to later ages by behaviors that enhance cognitive reserve: among these, she emphasized physical exercise and cognitive stimulation through learning new skills.

I immediately identified the trajectory of high cognitive reserve with my mother’s late-life experience—it was a stunningly close match to my visualizations of her aging literacy shown in figures 3–5. The timeline I reconstructed corresponds uncannily to the last fifteen years of the hypothetical woman with high cognitive reserve in Kennedy’s interpretation of figure 7: like her, Virginia functioned well until beginning to decline five years before death and spent the last 2 and ½ years in professional care. What would it mean to recognize my mother as a person whose aging reflects high cognitive reserve? I was intensely curious to learn more about this phenomenon.

I followed a citation trail that led me to Christopher Herzog, Arthur F. Kramer, Robert S. Wilson, and Ulman Lindenberger’s (2009) synthesis of empirical research supporting the more general hypothesis that individuals can positively influence cognitive aging by engaging in activities of “cognitive enrichment,” including physical, social, and intellectual activities (3). In the conceptual framework they propose, there is a “zone of possible development” for a person’s cognitive potential at any age, “a form of behavioral plasticity that is continuously reshaped by the individual’s environmental context, biological state, health, and cognition-relevant behaviors” (4). This zone defines a range of “possible selves” or life trajectories that lie between the lower and upper boundaries of the zone (8). Individuals’ paths through this zone—the height and length of their trajectory—are partly self-determined by their ability to adopt cognitive enrichment behaviors, both early and late in life, that optimize their potential for performing at the top end of their personal range for as long as possible.

In focusing on adults’ agency in determining this trajectory from maturity through old age, research on cognitive reserve recognizes the role of contextual variables, but doesn’t address the complex interrelations of genetic, biological, social, and experiential factors that encourage, facilitate, limit, or inhibit individuals’ ability and desire to practice enrichment behaviors. I’ve touched on some of those factors that enhanced or diminished Virginia’s resilience (e.g., level of nutrition, emotional stress, illness, social support) in old age, but this doesn’t account for the advantages accumulated over the life course that helped her age gracefully, which is beyond the scope of this essay.[xxiii]

This theoretical model of cognitive reserve and the research that supports it seemed to validate as well as explain my own empirical findings and judgments about my mother’s aging literacy, even in the details. For example, research confirms the negative impact on brain structure and function of the kinds of stresses I documented (Herzog, Kramer, Wilson, and Lindenberger 7). Cognitive enrichment theory supports my inference that increased physical activity and better nutrition (facilitated by a caregiver) enabled my mother’s mini-bounce-back at age ninety-seven (see figure 4). The steepness of my mother’s decline after its late onset, precipitated by an “increasing cascade of loss,” characterizes individuals with high cognitive reserve (Herzog, Kramer, Wilson, and Lindenberger 8) My uncertainty about distinguishing dementia from “normal” cognitive aging is justified by Herzog and his colleagues’ decision to place dementia and age-based cognitive aging on a continuum of cognitive impairment, treating their differences as primarily quantitative (10). Even my highly personal choice of “resilience” to name the pattern of my mother’s aging resonates with how scientists use this term (more narrowly) to refer to how people effectively adapt to or resist the effects of aging and brain disease (Stern and Reserve, Resilience and Protective Factors PIA Empirical Definitions and Conceptual Frameworks Workgroup 1306).

While I was fascinated—and gratified—by the way this model illuminated and reinforced my findings, that was not what mattered to my “sense of an ending.” The difference it made was to recast dualistic relations that run through this essay, rebalancing and integrating them into something more like a double dialectic. As originally written, I interpreted one of these dualities as a progression: my laser focus on my mother’s unique history as an individual gave way to a powerful awareness of her commonalities with others in suffering the limitations and losses of old age (“age as a leveler” that washes out differences). As I wrote then, “Life, or the activity of a self-organizing being, is about creating order in the face of entropy, but the limits of resilience lie in mortality itself, especially as the individual tries to integrate growing life wisdom across time scales from autobiography to culture and history.”

Herzog and his colleagues did reinforce this perception, showing how Virginia’s highly specific, apparently idiosyncratic experiences fit into larger patterns of aging that set ultimate boundaries for lifespan development. As they remark, “even individuals who engage in optimal enrichment behaviors will probably experience adverse cognitive changes at some point in the end-game of life” (Herzog, Kramer, Wilson, and Lindenberger 49). As these worsen, the individual reaches a threshold of dysfunction at which “goal-directed cognition in the ecology will be compromised” (Herzog, Kramer, Wilson, and Lindenberger 5).

But Herzog and his colleagues give equal weight to individuals’ uniqueness from an ecological perspective: “Each of us develops and grows older in our own unique niche, which we co-create with nature and the physical and social environment” (5). Within boundaries that limit potential, they emphasize how much of a person’s resilience is self-created: their “core argument is that the life course of the individual is forged from experience and choice” (7). If, as scientists tell us, engagement in physical activity and cognitive stimulation build cognitive reserve (the earlier in life the better, but still developmentally possible in old age), then my mother shaped her own trajectory by her choices from a young age. Although no athlete, Virginia took many physically challenging trips in yearly travel from her fifties to her mid-seventies and maintained heart health to the end of her life. Her lively, wide-ranging intellectual curiosity was manifest in habitual daily reading from childhood through old age, simultaneously reading multiple books plus daily newspapers and journals.[xxiv] While she developed deep knowledge of many subjects and authors, she remained the consummate generalist, always open to new topics and areas of learning.[xxv] In other words, she engaged in the primary behaviors said to build cognitive reserve and support resilience.

Christopher Herzog, Arthur F. Kramer, Robert S. Wilson, and Ulman Lindenberger’s framework, and the research I read about cognitive reserve, made it possible to reconcile competing perspectives of my mother as a unique individual, with a distinctive historical “becoming,” and a person participating in common cultural experiences and universal patterns of aging, whose inability to complete an end-of-life project is an expression of our shared mortality. I experience them now more like simultaneous gestalts I can shift fluidly between, in the phenomenological process of “varying” perceptions. (And I understand there will be many more gestalts, as placing my mother’s life course in time, history, and culture fills in the spaces between the two extremes of uniqueness and universal humanity.)

This intellectual shift has its parallel in an affective one, rebalancing what I described earlier as the positive and negative aspects of aging literacy. When I deliberately chose in this essay to make the forces of decline the figure against the ground of Virginia’s late composing, it inevitably took on an elegiac tone, mourning what was lost. But what I feel now more vividly—at the end of her life, as I end this essay—is pride and pleasure in the stubborn longevity of her literacy. I can celebrate how far her resilience carried her: how long she sustained her composing effort, in the face of so many obstacles; how much she accomplished in a composing task that was by definition unending, since she never stopped learning: there was always more to add, to update, to integrate. In the words of Florida Scott-Maxwell, “We who are old know that age is more than a disability. It is an intense and varied experience, almost beyond our capacity at times, but something to be carried high. If it is a long defeat, it is also a victory, meaningful for the initiates of time, if not for those who have come less far” (1).

EDITORIAL NOTES

[i]]We wish to acknowledge the full list of authors who contributed to the texts cited here. For Bazerman, “Taking”: Charles Bazerman, Steve Graham, Arthur N. Applebee, Paul Kei Matsuda, Virginia W. Berninger, Sandra Murphy, Deborah Brandt, Deborah Wells Row, and Mary Schleppegrell. For Bazerman, Lifespan: Charles Bazerman, Arthur N. Applebee, Virginia W. Berninger, Deborah Brandt, Steve Graham, Jill V. Jeffery, Paul Kei Matsuda, Sandra Murphy, Deborah Wells Rowe, Mary Schleppegrell, and Kristen Campbell Wilcox. It is LiCS' editorial policy to name all authors of a text in cases where “et al” is used. We do this because “et al.” can obscure the full contributions of all authors, instead centering the efforts of a single author. We also recognize that when many authors have contributed to a text, the list of names in a citation can make it hard for readers to follow the paragraph they are reading. In such cases, we include a note like this one to name and make visible the efforts of all contributors.

[ii]We wish to acknowledge the full list of authors who contributed to this text: Tania Zittoun, Jaan Valsiner, Vedeler Dankeert, João Salgado, Miguel M. Gonçalves, and Dieter Ferring. It is LiCS' editorial policy to name all authors of a text in cases where “et al” is used. We do this because “et al.” can obscure the full contributions of all authors, instead centering the efforts of a single author. We also recognize that when many authors have contributed to a text, the list of names in a citation can make it hard for readers to follow the paragraph they are reading. In such cases, we include a note like this one to name and make visible the efforts of all contributors.

NOTES

[i] See Per Linell for a definition of dialogism that captures the worldview implied in calling my memoir “dialogic.” He describes dialogism as other-oriented, viewing human beings as ineluctably interdependent: methodologically this means that “relational wholes and interactions are the basic ontological primitives and analytical primes” to be studied (15). Among the concepts he attributes to dialogic thinking are interactivity, contextuality, and semiotic mediation (13–14). See section VI on ecological theories, which by this definition are dialogic.

[ii] In an archive created for my project by librarian Lindsey Hutchison, unpublished writings by Virginia LaRochelle Wetherbee include a book-length memoir, a collection of stories about the family, and numerous essays. She published a humorous account of our family life in the Ladies Home Journal in 1951 (“Too Many Chiefs and No Indians”) and two essays in The American Scholar: “Life with Father, Life with Socrates” in 1982 and “The Golden Age of Eccentricity” in 1983. Since most of her unpublished writings are undated, part of my ongoing research for the memoir is constructing as accurate a timeline for them as possible.