Abstract

This essay details the development of The Twiza Project, an initiative designed to allow students in the United States and Algeria to engage in on-line dialogues on issues such as human rights and democracy. At a time when there is a global crisis in democratic institutions, the goal was to enable students to collaboratively develop frameworks and responses which would address the crises of their specific contexts. It soon became clear, however, that while “social media” might allow terms, such as “human rights,” to circulate back and forth in their conversations, when embedded in the materiality of their lives these same terms seem to lead to unavoidable conflicts amongst them. It is out of such conflicts, out of such contradictions, we argue, that new democratic strategies and human rights practices much emerge. |

Keywords: community; partnership; politics; literacy; neo-liberalism; critical pedagogy; transnationalism; decolonialism; digital spaces

Contents

Justice, Democracy, Rights, and Progress

Collective Trauma and the Goals Of Democratic Education

Democratic Work in the École Normale Superieure, Algeria

Diminishing Discord at Syracuse University

The Hopes, Reality, and Post-Trauma Work of the Twiza Project

Human Rights as Locally Enacted

Enacting Pluriversality: Of Rights Without Guarantees

Introduction

It has become a truism that over the past decade, many countries in the Middle East and North Africa have been in a period of political transition towards (or perhaps away from) democratic structures. Within that truism, we believe, has often rested a false sense that the United States is somehow not also in a similar state of transition, not involved in a movement towards (or away from) its own democratic heritage. The election of Donald Trump has surely changed this sense of stability. Today, a shadow of authoritarianism lingers over both regions. Thus, despite one of us hailing from Algeria and the other from the United States, we now find ourselves consistently invoking a similar mission for education–the creation of classrooms focused on concepts of civic leadership and human rights that can support democratic social/political change within our respective nations. And we find ourselves consistently wondering how, despite geographical distances, we might combine our pedagogical efforts to confront authoritarian practices, enabling the next generation of democratic leaders and activists to see themselves in alliance with other such advocates across the globe.

Our collective hopes are occurring within a disciplinary moment where the ability of social/digital technology to support such transnational pedagogies is often also optimistically aligned with arguments about the creation of new politically liberatory spaces for those involved (Rice and St. Amant). Within this framework, arguments about a hybrid embodiment have also emerged, where digital spaces become linked to off-line activist practices for expanded democracy in both local communities and national contexts (Bridgman; Ghonim). Experience has taught us, however, that national, digital, and personal borders are not so easily crossed (Scott and Welch); that democratic alliances are not so easily embodied (Parks, “Sinners”); and that concepts of “justice,” “progress” and “rights” exist within a pluriversality of histories and standards (Mignolo and Walsh). Indeed, we have come to believe it is in the friction caused by such transnational dialogues, in the differences in technology access, in educational framings, and in politics through which the seeds of an alternative future will first be articulated; and it is in the resulting locally embodied conceptions of activism that actual change will first emerge (even when such embodiments “contradict” political framings of our global allies.) (See Lawton, Cairns, and Gardner; McDonough and Feinberg; Demaine).

It is within this contradictory and complex context, then, that we intend to discuss the genesis of the Twiza Project. Initially premised on the imagined ability of a seemingly seamless transnational digital space to foster an online dialogue focused on justice, rights, and democracy, our initial partnership (out of which Twiza would emerge) hoped to link such dialogues to the work of writing classrooms already focused on civic engagement/leadership. We intend to use the hope that initially informed the beginnings of our work to discuss how the reality of differing political contexts and traditions provided an alternative sense of what a transnational dialogue might produce among students. To do this work, we will begin with an overview of how Composition/Rhetoric has imagined its relationship to concepts of justice, rights, and progress. We will then provide some background on Algeria’s political/education context. At that point, we will discuss the experience of our linked classes, ending with how this experience led us to create (and then expand) the Twiza project.

Ultimately, we will argue that while the instantiation of such an alternative transnational framework might create unresolvable contradictions for those involved–disrupting the idea of borderless space–it simultaneously points to the demanding work that must be undertaken. Our current work, then, has turned to creating out of such inherent contradictions the possibility of a relationality and collaboration under the banner of multiple forms of “truth” and “traditions” and pointed toward multiple forms of justice (Mignolo, “Delinking”). It is that shift in action that we hope to document in what follows.

Justice, Democracy, Rights, and Progress

It is difficult to announce an origin point for when the field of composition and rhetoric associated itself with concepts of justice, democracy, rights, and progress. While it is possible to claim roots as far back as ancient Greece (Corbett and Connors), for our purposes we will situate this claim within the post-World War II period in the United States, when there was an attempt at a national consolidation on the meaning of “democracy,” as well as its consequent exportation as an economic/political model globally. As has been discussed elsewhere (Parks, Class Politics), this initial post-war articulation of our field as a nationalized entity is best encapsulated in the 1960 NCTE The Teaching of English and the National Interest, a document which positions the field as fully supportive of the Cold War politics of the time. Indeed, even when the field later drew upon social movements to create progressive classrooms as a counter-model to such politics, invoking the Southern Christian Leadership Council’s Civil Rights campaign and Students for a Democratic Society’s anti-war activism, such pedagogies often remained predominantly couched in a sense of American exceptionalism–often eliding or misrepresenting anti-racist/anti-colonial framed movements, such as elements of Black Power (Kynard, Vernacular) and later stages of anti-war activism (Parks, Class Politics).

Indeed, as a model to justify the simultaneous critique of US democracy from the inside (Civil Rights Movement/anti-war protests) while also being broadcast as an international model of democratic idealism (Marshall Plan, Peace Corps, etc.), this framework of democracy, rights, and justice was seemingly able to balance contradictory forces, demonstrating how the US could critique its own democracy while “fighting” for democracy elsewhere. For in each case, the field of struggle focused on reforming nation-state structures (US government and Viet Nam) within a sense of the American “ideal.” And within the field of Composition and Rhetoric, it is possible to understand many of the field’s progressive turns during this period as occurring within this “rights” framework–consider the Students Right to Their Own Language, an appeal for including more voices in classrooms/society within an argument about the “promise” of the United States (Parks, Class Politics).

We choose this moment, then, to highlight the extent to which the field of Composition and Rhetoric in its modern period initially established its democratic ethos (and sense of rights) within a particular sense of “justice.” Here we are aligning our argument with Nancy Fraser, who has argued that appeals to justice have typically occurred within nation-state structures where the “who” making the appeal was assumed to be the citizen, and the endpoint was either economic improvement or cultural recognition by the nation-state (Fortunes). (Again, think Students’ Right .) In this regard, Fraser stands in relationship to other scholars, such as Wendy Hesford, who understand the concept of “rights” to be premised on the fact of nation-states articulating and enforcing them (Hesford). Working within these scholarly paradigms, we are arguing that justice within our field has been understood as the moment when articulated rights, emerging from contexts of equal/expanding participation (i.e., social movements) are implemented within nation-state contexts.

And if you look at the genesis of justice-oriented service-learning and community partnerships within predominantly white US-based universities (the unique histories of HBCU/HSI/Tribal Colleges excepted; see Sias and Moss for part of this history), there is a clear emphasis on creating programs where formerly under-recognized communities were positioned to argue more effectively for justice, for the right to certain types of economic and cultural participation within assumed nation-state structures (Flower). Parks’s own work, along with the powerful work of Paula Mathieu and Eli Goldblatt, might serve as representative examples. In each case, the discussed projects are pointed toward intervening in local discourses, enmeshed within cultural and legislative power networks, with the aim of opening up participation rights of local communities in public decision-making practices (Mathieu; Goldblatt; Parks, Gravyland). This was an important articulation of democracy, rights, and political progress in post-WW II Composition/Rhetoric. And in the case of Goldblatt and Mathieu, important contributions were made.

Situating our work on democracy, rights, justice, and progress within an historical context, however, also exposes the underbelly of such desires, an underbelly premised on colonialism’s drive to define the “world” within a singular framework of what constitutes progress, as well as an economic and knowledge production framework premised on legitimating systemic exploitation of workers, both industrial and rural (Quijano; Spivak). Under this particular articulation of justice, democracy, and rights, for instance, two-thirds of the world were seen as essentially lacking the rhetorical, intellectual, or political skills to successfully integrate themselves into what is defined as a singular, unified concept of “progress”–a progress here defined as nation-states’ acceptance (forced or not) of US versions of democracy supportive of global capitalism. And as Hesford has argued, more often than not, arguments to “recognize” or “identify” with victims of human rights abuses, often from failed nation states, are typically premised on these very categories of what counts as “progress” (Hesford). (Our field’s accountability in such narratives is a topic for another essay, but we would point you to Mignolo and Walsh for a possible lens of interpretation, as well as the work of Ruiz and Sanchez for how these paradigms have impacted key terms in the field.)

Today, the original post-WWII instantiation of global capitalism, premised on strong nation states moderating its excesses, has been replaced with a neoliberalism premised on weak nation-states abandoning any role in moderating capitalism as well as any protection of public sectors/workers’ rights, all in the name of supporting transnational corporate profit. In such a world, a rhetoric of transnationalism, border crossings, and flows has infiltrated how classrooms are framed as well as how our “justice” work is understood. As Tony Scott and Nancy Welch have argued, one result of a lack of focus on the materiality that produces “open borders” is that our students’ “bodies” are being divorced from their “writing,” particularly as they are asked to imagine themselves as writers within this new transnational and traveling community (Scott and Welch). Instead of locally situated bodies, their identities become recoded as floating signifiers of the possibility of global communication, seemingly placing them in collaboration and partnership with individuals/communities across the globe (Sanchez, as cited by Scott and Welch). It is out of this context that the imagined hope of “transnational dialogues” appears.

By focusing on the “flow” of voices and ideas, however, Scott and Welsh conclude, our field has turned away from (ignored) the actual bodies that make such “flow” possible–the underpaid workers who mine the minerals which support cell phones, the non-union workers who have to fix the cables on which conversation travels, and, the nation-states held in an unequal relationship with first-world countries whose citizens (we use that term deliberately) enjoy the benefits of the immediacy of global communication. In such a framework, concepts of “justice” need to be reattached to the embodied needs of these exploited workers; “rights” need to be recast in ways that recognize the transnational community of laborers being exploited; and new models of civic engagement/democratic activism need to be formulated which can situate students in relation to (and in alliance with) other understandings of what “progress” might entail that support the liberation of locally oppressed bodies across the globe.

Clearly, then, we want to argue that another sense of “rights” and “democracy” is possible, one premised on a community’s local and historic practices, drawn from residents’ personal experience of living in historically colonized spaces as well as their experience of having their historic spaces colonized through the western models of nation-states existing within a neoliberal global economy. Here we are thinking of the work of Mignolo and Walsh, who argue that there exist regions where, admitting the lack of any pure space, populations have maintained cultural/ethical practices that draw primarily from non-capitalist/colonialist communal standards. As examples of such practices, we would point to the resistance practices of Indonesian communities confronting “loggers” who want to describe the forest as “empty” despite generations of families having practiced traditional farming technologies on that land (Tsing) and to the feminist collective Tejido de Communication para la Verdad y lad Vida, who invoke local concepts of palabrandar to resist strategies designed to take their land and co-opt their leadership (Mignolo and Walsh). Focusing on more disciplinary-based research methods, we would point to the work of Ellen Cushman and Lisa King et al., who draw upon indigenous practices premised on relationality to talk about how Native American communities are structured and should be represented in archives and scholarship (Cushman, “Wampum”; King et al.) and, finally, to the work of Adam Banks and Cristina Kirklighter, who actively listen to the traditions of African-American and Latinx communities as guideposts for how to proceed, how to align their work with definitions of progress emerging from the community (Banks; Kirklighter).

For us, the importance of these other models is in their attempt to articulate a sense of rights and political participation that emerges from histories/epistemologies that do not originate within US/European modernist frameworks. In this sense, they are “otherwise,” attempting to move toward a relationship with a colonial history instead of existing within such a history, i.e., indirectly invoking liberatory frameworks that participate/emerge from that very colonial history such as “progress,” “economic rights,” and “globalism.” What we are suggesting is that as the field moves toward a sense of itself and its classrooms as “transnational,” there is a consequent danger of encoding the colonialist models of “rights” and “democracy” into our students, models which were initially used to steal land/resources from existing societies as well as to invoke nation-state models (premised on US versions of democracy) that allowed an elite segment of that society to retain/gain power over the needs of the mass of the population (Butler and Spivak).

Aligned with the work of the above scholars, we argue that a “transnational” disciplinary effort (research, community, and classroom-based) must exist within a “pluriversality” of epistemologies and practices. Such an argument, however, poses questions to a field imagining itself within a “transnational” context but typically deploying US-generated concepts of democracy and state-protected rights:

- How do western-originated concepts of “human rights” fracture when articulated within global contexts? Do these alterations also fracture the meaning of a “transnational” space?

- How might the new forms of relationality created through embodied local histories and epistemologies also potentially reframe the goals of student transnational collaborative dialogue/work?

- How might such relationality be enacted by students outside of the writing classroom in local communities? How do we make sure decoloniality does not become a metaphor instead of an interventionary practice?

- How do such actions stand in relationship to the concepts of rights and democracy that have framed progressive work in composition and rhetoric?

Heading into our collaborative project, these were not the research questions we imagined. Initially, the Twiza project was premised on an Algerian concept closely aligned with a “barn building,” where a rural community joins together to build an important structure for a neighbor. The initial thought was that the students in our classroom would mutually build a new, online dialogic space that would enable a common vision across national borders to be developed on the meaning of justice, democracy, and rights–a vision that could then be deployed in local acts against existing cultural and government structures embedded within neoliberal policies. Just as practice norms theory, however, so implementation humbles hope. And the above questions emerged as each of the students’ local and national contexts created friction, demonstrating an inability to create a seamless transnational framework which could circulate online as well as in the streets and neighborhoods of a community. The dream of a unified space, that is, conflicted with the necessity of a pluriversality of knowledges. Traditional disciplinary concepts of dialogue began to falter, demanding that new ones emerge. We ultimately moved from a modernist-Composition premised in post-WWII frameworks to a new space, premised on a pluriversality of possibilities. We are not arguing the project became “decolonial,” but rather it began to rest on the edge, the promise, of such options.

It is to the importance of that theoretical and political movement that we now turn.

Democratic education necessarily occurs in what, to echo John Dewey, might be called the unconscious influences of the environment, the emotional, political, and historical resonances that form a “national identity.” Within the context of Algeria, this unconsciousness is infused with a colonial legacy that shapes the inter-relationship of concepts such as identity, knowledge, and heritage, often within the current context of sectarian conflicts. This complicated landscape is further infused with a collective memory of trauma—initially by colonialization, then with the struggle for independence and, most recently, with the violence of the Black Decade, a decade which saw over 200,000 civilians killed and entire villages massacred (Evans and Phillips).1 Within such a fraught context, the production of a post-colonial education focused on civic engagement and democracy is being articulated within a space where the political borders drawn around the meaning of human rights and democracy has also become a restrictive force to their very implementation, rights being simultaneously announced and rendered mute.

Indeed, such a framing can help us understand the current leadership of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika (elected four times since 1999), who in response to the Black Decade invoked a discourse of reconciliation through initiatives focused on “healing” and “dialogue.” That is, the government represented itself as the bulwark against violent and “traumatic” possibilities seemingly inherent in large-scale citizen political participation as well as the endorser of certain limited forms of civic dialogue concerning the future of Algeria. Here it is worth citing the argument of Wendy Hesford, who has argued the image/framework of trauma often removes the historical complexity of events like the Black Decade, substituting a “universal subject” who is then rescued by Western-originated concepts of human rights, rights often articulated through neo-liberal models of economic growth and governance policies (Hesford). In the case of Algeria, it is possible to understand the move to politically define this historical event as “traumatic” as a means to step outside the complexity of events (which might lead to attribution of guilt for parties involved in the Black Decade) and implement political rights that are framed in the service of such global economic trends.

And here the Algerian Ministry of National Education should be seen as a primary vehicle to instantiate this political and civic culture, using its centralized authority to mandate common curricula as well as standards (and thus civic values) for primary and secondary classrooms across the nation. Within the Algerian education system, for instance, the curriculum is generally geared towards the formation of the citizen, with this term often being preceded by terms such as good, active, decent, responsible, effective, and global (Hachelaf). Yet the Orientation Law of 2008 also situates this “good” citizen within larger national and international contexts that align it with neo-liberal frames:

Since the end of the last millennium, Algeria has undergone rapid transformations at both the political and economic levels: democracy, citizenship, human rights, individual and collective freedoms (which have gradually become concepts in our daily lives), market opening, globalization of the economy, internationalization of information and communication are no longer mere slogans but concrete facts. The task of the school in the face of these developments is essential. In addition to its traditional task of transmitting knowledge, the child should be taught how to become a responsible citizen, able to understand and contribute to the changes in the society in which he /[she] lives.

Within such a context, the “good citizen” becomes the individual who embeds their understanding of political rights with the neo-liberal paradigm of market openings and the globalization of the economy. Markers such as race, ethnicity, social class, language, gender become erased within such a national discourse and within such policies of economic liberalization. That is, a focus on the individual, not communal identity, dissipates the importance of collective action for economic/political change (Brown; Davies). In such a framework, then, Algeria’s educational mission is articulated into a global neo-liberal identity, with firm parameters on the meaning of democratic activism to produce change.

Both elements of this curriculum (neoliberal attitudes/limited democratic possibilities) can be seen in two sample student assignments. Consider the following example from an official First-Year Secondary school which invokes values distant from the traditional and current Algerian culture (Riche et al):

Figure 1. Teaching Civic Values, Students' Book: At the Crossroad.

The example of “take your elbows off the table” implies an Algeria where all communities use (or should use) tables, while, in fact, many cultural groups still sit on a carpet to take their dinner. The objective of this “poem” seems to be to socialize learners according to the values of the dominant socioeconomic group or class: those most benefitting from a globalization premised on Western (white) middle class civility (Auerbach). Thus, while it is important to acknowledge progressive trends to introduce global citizenship, through themes such as tolerance and intercultural understanding, it is equally important to understand the economic endpoint of such efforts often work systemically to further divide citizens economically. For, in the model being taught, traditions that are “otherwise” to global capitalism, offering alternative models of community/democracy, are moved to the side in the name of progress. A history of indigenous communal values captured in a dinner held on a carpet is replaced with a Westernized dinner table.

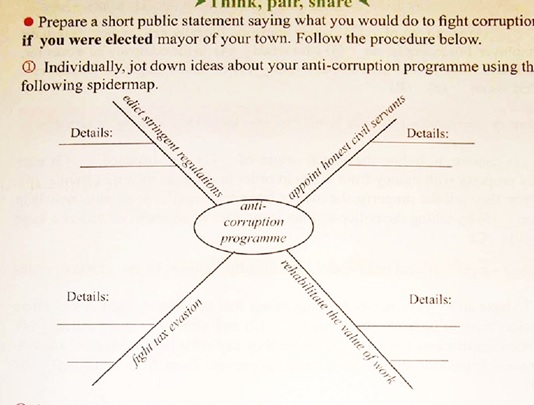

Within this framework, political critique or civic engagement is also mutated into limited visions of democratic activism. Ideally, that is, a democratic education produces informed citizens with a collective political voice in public life. Yet in one of the few examples of such education in the Algerian curriculum, only limited channels are offered for such public engagement in political change. When students are asked to write a persuasive essay for their imagined campaign to be a mayor committed to reforming corruption (see below), that is, the suggested pathways imagine a “leader” who can dictate solutions, a leader who does not also consider the larger economy of laws/regulations that foster an inequity that works in concert with limited access to networks of power.

Figure 2. Teaching political engagement: Students' Book, New Prospects.

That is, how open can an authoritarian system become when considering “corruption”? To what extent might such corruption ensure a continuance in political power at odds with democratic practices and norms? Indeed, within the MENA region, the actual result of a nation’s movement toward free market polices has been the creation of a clique of individuals, aligned with the government, who reap the rewards of privatization, further removing the government from being responsive to the will of the people (Achcar). Speaking broadly, then, if neoliberal economics fail to foster actual collective democratic rights and a robust civic culture longer traditions of communal decision-making/justice might offer an alternative. As evidenced above, however, such alternatives are effectively removed from the curriculum.

Negotiating “trauma” for educators/activists in Algeria, then, means exploring how to ensure such moments are not invoked in support of policies that promise safety at the cost of economic justice. Instead, education should exist within a complex history, one framed upon pre-nationalist traditions and arguments that demonstrate the value of dialogue and engaged citizenship practices to produce peaceful change. And such pedagogies, such curricula, should present an alternative vision that is wide enough for all identities, across indigenous histories and irrespective of their geographic location or racial/linguistic background, to flourish peacefully in ways separate from economic imperatives. In Algeria–and as will be seen below, the US–educators must work to produce a pedagogy that positions their students not only as “otherwise” to dominant culture but with the tools to foster actual change.

It would be incorrect, however, to imagine that such pedagogies are not emerging or already in practice in Algeria. Hachelaf’s pedagogy is a case in point. His classroom practices emerge from a lesson concerning the Arab Awakening: drastic change can easily be confiscated. As a result, he came to believe the classroom offered a site for sustained support of broader conceptions of civil/civic society. And he came to believe that for such a classroom to be enacted, students needed to become publicly engaged in their own communities. Hachelaf joined the École Normale Superieure, then, with the aim of training future teachers to show how their classrooms could produce leaders focused on such systemic and sustainable change. That is, he wanted students (both his own and those of the future teachers) to learn that the duties of citizenship transcended the limited visions of civic behavior and democracy dominant in MENA political culture, that if there was to be a counter-balance to authoritarian impulses that currently limit the meaning of good governance in the MENA region, educational institutions could enable a generation to move towards a broader conception of rights and justice than neo-liberal economic/political paradigms allow.

Since that time, Hachelaf has attempted to use the limited autonomy available to him as a university lecturer within a centralized system to design courses focused on producing the next generation of democratic leadership. His courses aim to provide students with a different perspective to reactionary pedagogies (discussed above) that have prevailed within education, where curricula objectives were too often intended to integrate students into the economic limitations of a “post-traumatic” state. In that sense, his class strives to be a reflective space to create a counterbalance focused on democratic education, civic engagement, and participatory leadership. Here the classroom is understood as a micro-version of the larger society, where teachers and students inhabit (and are not divested of) their personal, political or indigenous identities. The goal is to see how, out of an alliance of such identities, collectivities for change can be created.

With this in mind, one of the key concepts discussed is power distribution. In Hachelaf’s university classes, students engage in reflection activities such as designing circle diagrams representing factors such as gender, age, tribal, and sectarian affiliations that dis/able them from moving freely up social, economic, and political ladders. The discussion leads to a deep understanding of how the classroom is also socially stratified, opening up insights into how seemingly small pedagogical policies that teachers feel are benign or even good teaching practices may be harmful. For instance, a teacher who decides to design a social media project or a website to exchange course materials might hinder a segment of the classroom population that lives in an area without access to Internet, thereby privileging those already favored by society. Echoing Paulo Freire, Hachelaf’s class comes to understand that being critical in everything teachers do as educators forms the first step to a democratic and just society.

Hachelaf also creates spaces where teacher authority can be challenged. Outside the classroom, he encouraged future teachers to support and allow their students to form civil society groups. To this end, he presided and founded an “English Club” that offered students opportunities not only to practice this second language but also to debate local and international issues through student-student debates, excursions, magazines, environmental campaigns, and mock United Nations sessions. Unlike the traditional Algerian university classroom, where lecture dominates, these clubs provided the give-and-take of public debate, allowing students to enact the forms of critical and civic dialogue discussed in class through the lens of their own personal/cultural/regional histories. Here it should be noted that such clubs are highly unusual within Algerian universities. And it is also important to note that these École Normale Superieure student clubs have inspired similar efforts at dozens of campuses in central/southern Algeria. The growth of such clubs represents a proliferation, then, of spaces for civic debate to occur outside the knowledge frameworks of the mandated curriculum and other than the accepted viewpoints taught in schools.

We recognize that such efforts may appear somewhat ordinary to teachers outside of the Algerian context. They may not appear to enact the political work stated as necessary in the earlier section of this article. We want to highlight, however, that framing the work of teachers as facilitating students learning collective leadership skills, asking students to understand themselves as citizens fostering public debates outside of accepted paradigms, all within classrooms situated within a community context, are seen as radical departures by those in authority. In fact, in response to these practices, colleagues placed serious pressure on the university to re-assert traditional teaching models focused on teacher-centered/lecture-based pedagogies, their argument being that it was not possible to share power with students and effectively teach.

The clubs were seen as particularly objectionable as they allowed students to enact genres of debate and discussion that stood outside of accepted civil dialogue, moving beyond limited notions of what it meant to be an active citizen. Parents and authorities actually challenged these efforts, often seeking to eliminate any form of support. Unsurprisingly, then, when university students recently went on strike for increased educational/financial support, they were harassed. They were picked up, driven into the country, and left there to fend for themselves. Perhaps unlike the US, civic education in Algeria is not so much seen as neoliberal volunteerism but as a political commitment to citizen’s collective rights to organize and reform civic culture. And as the recent strike has shown, perhaps somewhat expectantly, such an education is seen as both disruptive and dangerous for those involved.

Diminishing Discord at Syracuse University

An English Club?

When Hachelaf visited Parks’s advanced writing class at Syracuse University, Donald Trump had been President-elect for approximately eight weeks. In the class period immediately after Trump’s election, a somber air of trauma and fear seemed dominant. In a course that had been focused on social movements, from Students for a Democratic Society to Black Lives Matter, the fact of President Trump seemed to take the wind out of our discussions, leaving many rudderless as they looked ahead. Hachelaf’s visit, then, focusing on the radical nature of sponsoring English Clubs in Algeria at first, seemed out of place, too moderate, not speaking to the current US context.

It was only in the following weeks that Hachelaf’s argument about creating alternative spaces for democratic practices and values gained increased relevance–particularly as proposed travel bans and ICE actions swept across the nation. Where, Parks’s students wondered, would be the safe spaces through which democratic dialogues could be fostered, expanded upon, and eventually acted upon in the public sphere? In many ways, it seemed to Parks that the students were adopting Nancy Fraser’s argument (an assigned text) about the need for subaltern counter-publics as a tactic to create collective platforms for intervening in dominant discursive political structures (“Rethinking”). In Fraser’s case, the focus was on women’s rights; for Parks’ students, the focus was on creating arguments about the political rights of all individuals in the US, regardless of race, heritage, gender, or legal status. At that point, Parks’s students could not be aware of future policies, such as those which would separate refugee children from their parents at the US border. They could not be aware of the future need for such expansive defenses of political/human rights.

Yet in those immediate weeks after the election, and echoing Hachelaf’s vision, the classroom became a space in which to frame concerns, to seek support and consensus on the value of collective deliberation, and to use the pedagogical space as an incubator towards a pathway forward. As discussion continued, it became clear that some of the students’ everyday experiences of racist encounters, sexual harassment, and anti-“immigrant” attacks demonstrated that the pre-Trump era was less a pivot point than a moment exposing deep historical “wounds,” suggestive of some alignment with Mignolo’s invocation of “colonial wounds” (“Delinking”). That is, it became clear that the public rhetoric on campus (perhaps in the larger culture) that framed these current encounters as “traumatic” had smoothed over a complexity that spoke to different historical legacies of colonialism and slavery into which the legacies and unique trajectory of sexism was often articulated. As both a means to frame their own experience, and a way to build a different collective identity together, “trauma” came to be seen as an inadequate conceptual tool for forward movement.

The writing produced for the remainder of the course can best be described as uneven as students struggled to locate themselves within that current moment, attempting to reinvent the history we had studied around political activism—with its own legacy of blind spots—into a productive space for dialogue. Academic theories intended to help students “invent the university” were twisted into “inventive” strategies to protest campus culture. And visual rhetoric assignments would be used to bring these conflicting histories, theories, and experiences into clashing images that attempted to articulate a future in which their voices would be heard. Unlike many of Parks’s courses, which often include producing a publication, none of this work would circulate outside class. For many of the students, in fact, there was a sense that there was no space on campus that would move their fledgling formation of an intersectional alliance and discourse into productive action. (On a local level, the students had seen such a formation at collective action against oppressive university structures, the General Body, be threatened with expulsion in the midst of a sit-in at the Chancellor’s office building (Mettus).

It was not until the following academic year, almost eight months into Trump’s presidency, that a vehicle emerged through which such student dialogues might be supported and concepts of intersectional alliance/community building developed. And in many ways, it was the digital version of Hachelaf’s English club. Parks’s new course was an advanced rhetoric/composition course focused on the rhetorics and practices of human rights advocacy, a course which included partnerships with local and international human rights activists. The local partner was a refugee resettlement project, where the students would work with young adults to record their experiences of living in Syracuse. Instead of Hachelaf, the international partner was based in a different MENA country and hoped to establish projects which foster progressive discussions about education and community building. Before the class even began, however, the MENA partner had to withdraw over concerns about the nature of such work in the current context of her country. Concepts of rights and justice, it seemed, did not flow smoothly across borders. Indeed, the classroom (which consisted of many students from the earlier class) had become enmeshed in global struggles over the meaning of education, human rights, democratic dialogue, and political progress. The question became how to respond.

Enter Hachelaf, his students, and the seeds of the Twiza Project.

The Hopes, Reality, and Post-Trauma Work of the Twiza Project

This article began with our belief that that while each of us work within different geographical locations, we began to see ourselves as facing a similar pedagogical issue: how to create a classroom which would enable a more expansive nuanced sense of civil/civic society as the basis for public engagement and activism. And as our conversations continued, we began to realize that both of our classes appeared to be situated within contexts publicly framed as “traumatic,” the limitations of which our students were trying to move beyond. When the withdrawal of the first MENA partner opened the opportunity to join our classes together, our hope was that such seemingly similar experiences might generate a virtual community that could lead to productive and material work by our students on expanding civil society rights/practices in their local communities, one that supported students attempting to create a “non-traumatic” future.

It is important to note that unlike the Twiza Project that emerged later, our initial collaboration was decidedly ad hoc. Parks’s course had already started; Hachelaf’s would begin in several weeks. Hachelaf’s students, who initially would respond as a collective group, not as part of an assigned class, would move to working primarily through a classroom focused on education theory; Parks’s students would continue to work outside the classroom with the previously mentioned refugee project and focus on literacy theory. In addition to different readings, there was also little to no coordination between the classes in terms of assignments. In fact, as the collaboration among students began, Parks altered the assignment expectations to include the work of developing specific writing prompts to initiate dialogues as well as building a website to archive the dialogues. At the outset, it was thought common prompts would be used by all students, including those in the refugee project. This idea was abandoned as it became clear the intensity of the US/Algerian student dialogue organically moved to a focus on the situated nature of human rights discourse (see below).

To meet this need for shifting and emerging strands of conversations, Parks’s students developed an online discussion tool using the platform Discord, which is more typically used as a gaming platform. Discord enabled the possibility of group conversations, specific topic conversations, and “closed” conversations among select students. The goal here was to enable a discussion on “human rights” featuring all the students in our class. As specific side discussions emerged, a unique conversational thread would be developed, and, when necessary, “closed conversations” would be created for students who wanted to speak privately with each other. In this sense, the discussion seemed premised on a concept of rights that was defined as transnational at its foundation–a belief in a common set of values and practices from which the needs of local circumstances could then be analyzed and public engagement created.

The initial prompt (used by all students in all locations) to introduce students to each other was “Describe a meal which represents your country”; this somewhat broad framing changed as US/Algerian dialogues became focused on the students’ current educational and political situations. At this point, abandoning “prompts,” the conversations began to focus on questions such as “What are human rights? What do they look like?” Perhaps if the course had been more formally prepared, different conversations might have occurred. But within this loose structure, Parks’s students almost instinctively entered such a discussion focused on the possibilities inherent in the new transnational dialogic “space” to support human rights–a move Hesford would have probably predicted. For instance, one student wrote:

When I think of a basic human right, I think about freedom of speech. I'll admit, being in a first world country, I take food, water, clothing, shelter and medical care for granted. However, the reason why I think that the freedom of speech should be an essential human right is because of what this Discord symbolizes. We are all equals here, with no one voice being treated as "better" or "more valuable" than another. We all exist in a community that talks about huge global issues that need solutions. These issues have immense challenges caused by the powerful and the wealthy who want to keep the status-quo. I can't imagine how much harder it would be without the ability to communicate with one another.

An example I would give would be North Korea (as it's covered in the media today). It's described as a place where the Kim family have reign over a starving country, filled with people who cannot express their wishes for a change in government. It doesn't surprise me that North Korean citizens have fled for China or South Korea when the rights to protest or democratically vote on policies don't exist. I can only imagine what North Korea would look like right now if the Kim Il Sung (the first premier and dictator of the country) had established freedom of speech and democracy for its citizens.

Long story short, so many ideas, talents and energy can work together in incredible ways when everyone is allowed to speak freely and their communication is valued equally (SU Student).

Here the framing of digital space as a utopic geography of equality is clearly articulated. Such a framing is immediately complicated by other Syracuse students who contrast the imagined free digital space of the dialogue with individuals who lack the right to a good education in “real life.” This alternative framing of unequal access to (or implementation of) rights within the United States, however, is then presented not so much as a result of the failings of the US but as individual communities not valuing such rights: “My community only had families like mine who gave their children no choice but to graduate high school and earn a higher education. So, I can’t even imagine growing up and education not being a priority” (SU Student). “Other” countries are then discussed as lacking similar commitments to fundamental human rights such as education. A Syracuse student, who was working with a child that was a refugee from North Africa and now living in Syracuse, wrote: “One of the students I was with pointed out that having a free education was one thing that she didn’t have back in her native country. Ignorantly, I never really thought about all kids not granted a free education.”

The failings of these other countries to support human rights was then expanded to political rights. After a discussion on how the United States has expanded voting rights, for instance, a Syracuse student writes: “There are plenty of countries who do not encourage or allows [sic] voting by either/any people at all or just a select few. . . A government must create opportunities and regulations that favor all, not just one person or group.” This final comment not only erases the current efforts to deny citizens voting rights in the US but also frames the current commitment to voting rights in the US in terms that slide into neo-liberal arguments about government creating “opportunities” to enact rights, not guarantees of such rights being enacted/enforced. If the US is marked by communities who fail to take advantage of their rights, “other countries” are marked, then, by the failure to “encourage” or even “allow” such rights.

To some extent, this framing of rights confirms Hesford’s argument that human rights discourse tends to work on a model of “empathy.” In using this term, Hesford implies not only personal concern for individuals who are denied voting in other countries but also an implied judgment that such failures speak to a lack of communal values and functioning governments. Note the empathy of the Syracuse student towards the young refugee child coupled with a judgment about her country, for instance. There is, Hesford argues, an implicit value judgment with echoes colonialist arguments that regions such as MENA countries lack certain Western traditions, traditions which might be profitably exported to these regions—perhaps with a dash of economic exploitation as well. Indeed, what this set of student comments demonstrates is how the embedding of such arguments within a transnational digital space demonstrates how such Western values are now being spread across regions. To reiterate the comment that began student discussion: “We are all equals here, with no one voice being treated as ‘better’ or ‘more valuable’ than another. We all exist in a community that talks about huge global issues that need solutions”(Syracuse student).

Here it should be noted that in the opening moments of the dialogues, students participating from other universities, such as the University of Djelfa students, also stepped into this discursive structure, this habitus of human rights. These students affirmed both the empathetic narrative as well as invocations of “trauma” from which citizens have a right to be protected. One student wrote:

Human rights cover all aspects of life, but for me one right stands for them all, and that is the right to live. Some people can’t even dream about healthcare or education, their only wish is to live to see another day. No one has the right to take an innocent life, but that’s something we hear every day especially in wars or other places where people are killed for no reason whatsoever. My heart aches whenever I see the news, or just hear about an incident in my city. We all have the right to feel safe, to live a stable life, to sleep at night without having the fear of someone breaking in and hurting us or our families. All in all, and to put it in fewer words to show how important it is to fight for this right, is that no other right can exist without it. (École student)

In this contribution, the right to safety is the fundamental premise on which all rights are based. And within the context of Algeria, the student notes how her “heart aches whenever I see the news, or just hear about an incident in my city.” Within a discussion of the government’s role to secure the opportunity for “rights,” this intervention also articulates the logic of the state protecting its citizens from such “trauma,” while often, as noted above, not placing such trauma within complex historical frameworks. Given the historical context in which the students were writing as well as the rights discourse in which they were situated (ala Hesford), these opening comments should have been predictable. The creation of a “We” premised on the spread of Western-based human rights as a buffer to the trauma and lack of political democratic rights facing non-Western countries seemed to be where the conversation was leading.

The students, however, soon began to try to actively disrupt this emerging empathetic relationship, “unsettling” it to invoke Hesford’s use of La Capra (2011). The lever that led to this disruption emerged through a discussion on how gender rights were (or were not) articulated as fundamental to human rights. In discussing the importance of education as a right for women, in particular, an École student wrote:

As a woman sometimes I think of what if I haven't been sent to school, how would my life be now, how do girls in my age manage to live a life that doesn't include any studies, any cultivation, or any plans for a future job that would give her an independent life to do something in the world no matter how small it is; therefore, I believe that for women to defend their rights they need to be educated and cultivated. (École student)

This fracturing of the universal subject of human rights, initially splitting into types of gender, led to a series of further articulations of identity categories which began to argue how any universal claim to a “We” had to be implemented through intersectional politics. A Syracuse student wrote:

Because I am a woman of color, specifically a black woman, these problems are only amplified. The stereotypes of being an "angry black woman" are constantly being thrown my way regardless of how passive or submissive I may choose to be in a particular moment. That reality is what has evolved me into the kind of thinking that makes me say women are to live their lives as they want them. Society will find a problem with an outspoken woman. They'll call her "bossy" or "rude". . . . This mentality is something I have to continuously reinforce as I navigate throughout various spaces but it is the only way to exist in the way I would like, while being conscious of my positionality relative to the person or space I'm interacting with at the moment. Being a woman of color in the United States includes a miscellany of emotions and politics but it's the intersection that most frequently informs who I am.

In response, an École student writes:

To be yourself, that is a woman in a world that is dominated by the male population is very difficult. . . . As for harassment, women are always the ones who are blamed for this act. We are always that one’s "at fault.” Even rape is regarded today as not that "important of an issue" anymore. I think the only way to solve all these problems of sexism and harassment is [for it] to treated as a "disease.” It needs a diagnosis, prognosis, and preferably a cure. Some men out there can do with a dose.

I know and I've heard of many examples of women being assaulted, harassed, or in the act of being abducted by some man in the street. Thankfully, at the time of these [incidents], things did not get that bad and the women were rescued. The big part in these stories is that the women in question did not file or complain about anything to the police. Most of them could describe the assaulter perfectly, but they didn't because she was afraid. They know that the man in question can get back at her and do worse things and no one would be the wiser. We are, in some cases, really afraid of some men because they are physically stronger than us. And men know that and sometimes they use it against us because they know we, in most cases, can't retaliate, especially when they give you that smirk which says: "I can hurt you woman, and you know it and I dare you to act on it." It is the bitter truth.

Within this emergent dialogue, there is neither the invocation of a universal subject of human rights nor the creation of a binary West/non-West geographic context. What emerges is a framework that demonstrates how human rights discourses can co-exist within structures that oppress/fail to account for locally specific acts of gender discrimination across borders. And unlike the initial articulation that began the class dialogue, these students are no longer in a transnational digital or geographic space where “We are all equals here, with no one voice being treated as "better" or "more valuable" than another. Instead, the question becomes what other traditions might be called upon to establish greater justice and rights for women. Indeed, it is at this moment, during this conversation, that students entered into a group conversation (as opposed to class-wide conversation). Instead of a transnational “free space,” then, a “digital hush harbor” for women students was created (For the concept of “digital hush harbor,” see Kynard, “From Candy Girls”.).

Human Rights as Locally Enacted

A conversation premised on a universal sense of human rights, enacted within an imagined “free” transnational space, had initially enacted what Hesford calls the empathetic rhetoric of rights discourse. As that conversation continued, however, students began to push back against a binary center/periphery framing, arguing that gender discrimination existed as an undercurrent in both students’ local experiences in the US and Algeria. While this critique was initially premised on individual experiences of harassment/assault, the conversation began to step outside of the personal concepts of an essentialized identity politics to a concept of rights as the creation of a locally created habitus from which gender discrimination could be confronted. The series of comments from which this transition occurred gained initial articulation from École students. In discussing the role of the state in supporting gender rights, an École student wrote:

One example of women gaining power in Algeria, as far as I’m concerned, has to be [one of our current Ministers]. . . She studied abroad, so she uses French instead which sounds ridiculous to me; not to forget her controversial ministerial decisions, because of which she is constantly being criticized. She’s a great example of women misusing their only chance to show how influential and powerful they can be, and it still amazes me how her being a woman combined with her wrong choices still didn’t affect her very important position in the ministry, which sheds light on how the whole topic of women’s power and equality is pretty messed up here in Algeria.2

It should be noted that here, again, the identity of the individual in question is fractured from a universal identity, first to a gender position, then to her linguistic/educational positioning, and finally to her ministerial position. For our purposes, it is also important to note how this comment separates the “identity” of the individual’s gender from a particular political stance. What becomes clear is that her failure to support gender rights exposes how the habitus created by the state was a weak/inadequate response to reform structures to enable women to recognize both the extent of their discrimination and the ability to argue for their rights. This recognition of the need for systemic change within the state then expands from the government to political parties. A different Algerian student wrote:

The Constitution of Algeria in 1976 incorporated the rights of women in the political, economic, cultural and social spheres. With regard to item 42, the Constitution emphasized gender equality. But honestly it is not enough. I had a last discussion with my friends and we were talking about political women, because last Thursday we saw the legislative elections. [One person] said, political women does not exist in our community, women are just tool under the use of men. I really do not care about her life or what people say about women's success. In no way will people criticize. I really appreciate political women although I hate to be one of them.

Here the student demonstrates how cultural attitudes limit the ability of women to enact a gender-rights politics within the state or political parties, even when the structure or “politics” would seem to be open to such transitions. Within these comments, gender rights are seen as emerging out of particular political/cultural contexts and, importantly, the discursive and material field of action seen as most relevant is not an abstraction to “human rights” but the local work within these complex cultural/political contexts.

As a result, what begins to occur, then, is a new model of rights arguments. There is less emphasis on appeals to human rights as a universal and more towards local traditions, whether emerging from religious or cultural traditions, as the seeds from which an increased enactment of “rights” is possible. And increasingly in the dialogue among the students in the two classes, an argument emerges which utilizes terms such as “allyship” and “intersectional.” One example of this is from an Algerian student, who had been writing about the importance of Islam to tackle gender discrimination in Algeria; this student writes to the African-American SU student:

The prophet Muhammad (P.B.U.H) said: There is no difference between the Arabic on the precepts and not between black and white except by piety. We are equal in the eyes of God, and people always criticize whether you are white or black, don't forget you have beautiful heart and beautiful soul. Although I don't know you but I imagine that so don't care what they say be yourself and don't pretending for them. We all face things that make us angry not because black women are always angry, you know Oprah is a black woman and a successful woman I like her. Believe in yourself that's all you need to convince them about your presence and important in life.

What is important about this moment is that while there is an alliance imagined among the two students, there is no call for both to share the same essentialist grounding in their local struggles. Working within the framework emerging from her fellow École students, the argument for gender rights will be premised on the Koran, invocations of women’s previous struggles for human rights (of which the Algerian constitution is one example), and a continued attempt to stitch together gender rights arguments across political/cultural institutions. In doing so, this student positions herself against the universal/government frameworks enforced by the United States’ foreign policies, policies often linked to neo-liberal and unacknowledged “Western” concepts. For the African-American student, as the student herself states, the work will be equally intersectional, only for her focusing on US based histories/arguments of feminism, Civil Rights, and a sense that government should “ensure that the citizens’ basic needs can be met,” here inclusive of economic rights. In doing so, however, she is also invoking frameworks that when enacted internationally by the US have actively worked against the collective rights of her “transnational colleague,” given how these rights campaigns are often also used to justify US intervention in other nations to enforce such “human” rights (Spivak).

Both students imagine constellations of ideas, identities, and institutions that expand the ability of women to move through society as equals, free from violence. Both argue from a position premised on the complex possibilities of their local/national environments. Yet in doing so, both produce contradictory appeals in the international rights-based context. To a great extent, the values invoked by the US student are exported in a fashion which only furthers the neo-liberal contexts and supports limited democratic states that the École student is positioning herself against. Ultimately, these students seemed to positioned in contradictory fashion to each other, even while imagining themselves as allies.

To reach an intersectional understanding between them, more work would need to be done. At this point, however, the term ended.

Still, however embryonic they were, these dialogues enabled students to re-imagine their digital transnational space as no longer moving from a disembodied position, flowing across borders. Instead, they began to recognize how “human rights” masked over legitimate political claims by specific populations, as well as how ultimately such claims should be based less on an essentialized identity and more on an alliance-based restructuring of positionality. In this very process, however, students also began to see how locally/regionally based frameworks ultimately pushed against transnational appeals to universal human rights, leading to potentially contradictory or conflicting local strategies and protests. And it is from this perilous moment of possibility and conflict upon which our new work will attempt to build.

That is, as our collaborative work moved forward, we formalized our efforts under the title of the Twiza Project, a term that invoked communal efforts to build important structures and also expand the classrooms involved, drawing in university students from not just the US and Algeria but Morocco and Kurdistan/Northern Iraq. We have redefined the classroom to include NGO educational programs in rural areas within the MENA countries, often disconnected from digital spaces but impacted by transnational flows of capital. The curriculum is also becoming more organized, moving from readings premised in Western concepts of rights to include a focus on indigenous communal practices within each country. Indeed, it became clear as the initial dialogues occurred that the epistemologies and communal legacies that students could draw upon were limited; they seemed divorced from the histories of the peoples who populated the land in which their classrooms were located, the communities that populated the land prior to neo-liberalism and colonialism. If the Twiza Project is to help students create a space “otherwise” than a Westernized framing of human rights, elsewhere than a framework supporting a neo-liberal flow of global capital, then we believe the students must understand the complex and powerful histories that have informed the geography upon which they will make their alternative future.

Finally, we intend for the Twiza project to directly provide training in the material skills of community organizing–the nuts and bolts of calling meetings, developing agendas, building campaigns, and assessing successes/failures. Too often, we have found that “dialogue” serves as an alibi for action; alternative futures remain metaphors, not disruptive practices. In this effort, however, we work with the realization that bodies move differently through local and global environments. The same act done by a US male citizen-student will not have the same ramifications as that of an Algerian woman student; nor can the political safety of any student of color in the United States be assumed or the willingness of governments in the MENA region to allow such civic activism be considered a given. If democracy is a “contact sport,” we act with the understanding that any education in activism also has to be an education in safety. To do otherwise, for Parks at least, would be to assume the privileges accorded to a white gendered male body, a body also named as a citizen of the US, could be the model upon which all activism can be premised. It would be, in short, a move back to a universalism that works against an “otherwise” future.

And at this historical moment, the world could surely benefit from something other than the status quo.

Since the initial drafting of this argument, traumatic events continue to occur–witness as one example children being separated from parents at the US/Mexico border, an act that in many ways moves beyond the ability of the word “trauma” or any other word to describe. At such moments, broad appeals to human rights certainly have their place. And within such a context of human rights abuse, we understand that a project such as ours might seem too small, too limited, or too insubstantial to meet the current need of this moment.

Perhaps, however, the Twiza Project can serve a purpose for our students, here and abroad, who see trauma invoked as a way to mask a political complexity which must be articulated, addressed, and resolved. Perhaps, students who are placed within a rhetoric of transnationalism and open borders, but whose daily life is seeing political borders hardened through racist appeals or imagined threats by democratic collective action, can use the Twiza Project to begin to find an alternative path forward. As the small sampling discussed above demonstrates, the power of a space to think through how their identity is being constructed, positioned, and actualized in this current moment begins the process of allowing another conversation to begin: a conversation premised on a knowledge of their local context, of the levers that might produce change, and of the possibilities a collective response might provide. Such conversations allow students to find an agency which moves beyond a traumatic response to concepts (and eventually actions) which realign political dynamics for a future that speaks to their aspirations and those of their generation.

It is a conceptual move, however, that leaves behind the seeming guarantees of a universal declaration of human rights, leaves behind a sense that the instantiation of such rights would even create the expansive definition of equality to which they seem to be heading. Such a conceptual move requires increased focus by our classes on the local traditions/frameworks of justice, historical moments of local activism which pointed toward a greater sense of equality. It would demand an education that provided the organizing tools which would enable material alliances to be drawn, collective bodies brought together, strategies that could produce change formulated, and plans to ensure that change does not quickly evaporate. It would require us, as teachers, to support our students’ aspirations for something better than this current moment.

This is the generation of the Arab Awakening and the Obama presidency, of Egyptian crackdowns and Trump Border Walls. It is a generation that has seen hope turned to despair, seeming progress followed by retrenchment. Our belief is that this experience has not left our students traumatized but determined to actualize what was momentarily glimpsed. Twiza is one attempt, however small, to keep open a space for such conversations, a space where local knowledges can be drawn upon to expand justice, democracy, and political rights. It clearly is not enough, but we have come to believe it is also not nothing. Perhaps at this moment, such a hint of possibility is enough to continue to move forward.

Notes

1For our purposes, it is important to note that the Black Death massacres occurred within the above cited collective historical memory of trauma and violence. As Franz Fanon argues, the impact of trauma and past struggles are defining features in the history of the nation, that such traumas live in the present and define tacitly or explicitly many aspects of the lives of the citizens. In his “Les Damnes de la Terre,” Fanon argued that trauma and violence can serve as a unifying force and that, in Algeria, it was the violence that arose in response to the colonists’ first violence that mobilized the people, throwing them collectively into “one direction” towards independence (Fanon). Writing decades later, Rahal sees the resort to such violence from that moment onward “as a form of Algerian fatality" (143), a central pillar of national identity. Unlike the independence struggle, then, the violence of the Black Decade became seen as something to be repressed, a symbol of the need to control mass movements for political freedoms which might spin out of control.

2As is well known, Algeria gained its political independence from France as a result of a fierce seven-year war. At the dawn of independence, however, schools were still staffed with expatriates using French materials. Through the introduction of an Arabization policy, Algeria restructured and re-staffed schools as well as universities with materials created by Algerian educators. (Kohli, 1987). Indeed, Arabization became a process of converting all French-dominated disciplines and sectors to Arabic and, as such, was "a reaction against the cultural and linguistic domination of France" (Aitsiselmi, 2006). In this sense, Arabization and the Algerianization of school materials were also part of a widespread movement to regain a national identity, reclaim natural resources, and participate in the production of a pan-Arab unity (Kawmia Arabia; Evans and Phillips). In critiquing a government official, the student is invoking the history of such educational efforts, indirectly positioning the official as little better than the colonizing educators who previously directed Algerian students’ educations.