Abstract

Agency is a central concern of gerontology, age studies, and life course research, but the role of literate action in supporting and perpetuating agency in older adult writers is not well understood. A conceptual framework for the relationship between agency and literate action would provide important insight into contemporary writing research on older writers. In this study, I trace the literate practices of one writer, Frank, in order to understand how he used literate action to both negotiate his lifeworlds and support his own agency in his life after his retirement from an engineering career. Drawing on posthumanist understandings of agency, I use a combination of sociohistoric (Erickson and Roozen) and sociological (Brandt) methodologies to trace Frank’s literacy history, the chronotopes for writing that he enacts, and the agency that he develops and supports through that chronotopic work. I focus in particular on the acts of textual coordination that Frank enacts, using those data points to understand how Frank creates objects in his daily writing that bolster his agency in future social situations—a concept I refer to as expansive agency. |

Keywords: literate action; agency; age studies; literate practices; older writers

Contents

Framing Agency: Chronotopes and Textual Coordination

Introduction

Literacy, variously defined, has been demonstrated to have a positive effect on the social, cognitive, and physical functioning of older adults. The social nature of literacy—the fact that our literate actions pull us into conversations with others, drawing us into social worlds that we would not otherwise be part of—not only brings literate actors into social organizations, but into configurations of cognitive, spatial, chronological, and material action that echo across multiple dimensions of human activity (Bazerman). In studies of older subjects, literacy is positively associated with reducing sedentary behavior (Gibbs et al.), supporting working memory (Rhodes and Katz; Manly et al.), and decreasing mortality (Sudore et al.).

While the benefits of literacy are clearly demonstrated in research on gerontology, psychology, cognitive science, and physical health, the ways in which literacy is taken up by older members of society—how, why, where, when, with what social and historical antecedents and consequences—are not well understood, although research by Lauren Marshall Bowen, Heidi McKee and Kristine Blair has begun to outline this work. In particular, the relationship between literate action and the agency of older writers—that is, their capacity to make choices that shape the construction of a social situation—remains unclear. Understanding the relationship between literate action and agency in older writers can provide significant insight into age studies.

In this text, I present a case study of Frank, a retired engineer who has, in the decades since his retirement, repurposed his literate practices to participate in a wide array of social activity involving friends, family, the local community, and far-flung networks of actors from across the country. The particularities of Frank’s affordances in retirement offers what Harold Garfinkel refers to as a “perspicuous setting” for the study of how literate action impacts the lives of older writers (Ethnomethodology’s Program 181). That is, Frank’s work as a writer during retirement brings into stark relief key aspects of the social construction of writing in later life for examination by researchers. Because Frank relies on such an interconnected set of literate practices to build his network of lifeworlds in his post-career life, a close study of those practices can indicate how literate action promotes, reinforces, and perpetuates agency in older writers.

I trace Frank’s literate practices across his life, the lifeworlds he participates in, and the audiences that he writes for in order to answer the following research question: How does Frank’s negotiation of his lifeworlds through literate action promote agency in his life after retirement? Drawing on a sociohistorically and sociologically situated theoretical framework and methodology, I identify the ways in which Frank uses literate action to construct situations post-career that are informed by a lifetime of practice and inform the ongoing development of post-retirement lifeworlds.

Agency and Age Studies

At the heart of understanding Frank’s negotiation of lifeworlds is the concept of agency. Agency is a central concern of age studies. In the introduction to his edited collection, Old Age and Agency, Emmanuelle Tulle notes that “what we know about later life is influenced by powerful discourses, such as medicine, welfare and neoliberal ideology and that it is at the meeting point of these discourses that we ‘imagine’ and produce later life” (ix). Our understanding of agency in old age is caught up within these discourses—agency is often seen as belonging to the cognitively and physically able, something seen culturally as slipping away from those in later life. As Tulle puts it, “older people appear to be in a Catch-22—whatever they do, they either postpone decline or have been caught up by it” (ix).

The work in and after Tulle’s collection has attempted to subvert these commonplace considerations of agency and aging in contemporary discourse. Explorations of the embodied nature of selfhood (Kontos), the role of identification with aging (Hockey and James), anxiety and memory (Herrera et al.), and dispositions (Francescato et al.) have worked to reframe such views, encouraging a multifaceted view of age and age studies that locates an individual not only along an age range but also within states of dispositions, individuated frames of reference, personal perceptions of opportunities for social action, and bodily movement within material systems of circulation. This multifaceted view challenges the commonplace notions that contemporary social discourse brings to discussion on agency and aging.

Such a multifaceted view of agency and aging must be kept in mind if we are to best understand how Frank’s literate action produces and extends agency in his life. In order to read Frank’s literate action without problematic commonplaces in mind, I draw on a posthumanist (Accardi) definition of agency, which sees agency as circulated, as established situationally through the interactional work of actors, human and nonhuman alike. Viewing agency in this way returns my attention to the material work of Frank—both his literate practices and the products of those literate practices. This view on agency both aids in avoiding a return to commonplace understandings of agency and enables an uncovering of the “radical withness” (Micciche, Acknowledging; “Writing”) within which agency is constructed, both by people and by objects.

Min-Zhan Lu and Bruce Horner, drawing on a Translingual perspective, suggest that, since “difference is an inevitable product of all language acts,” any use of language—which, by extension, constructs a social situation—is agentive in nature (585). “All writing,” they argue, “always involves rewriting and translation, inevitably engaging the labor of recontextualizing (and renewing) language, language practices, users, conventions, and contexts” (586). The use of language through writing and the marshalling of resources to make such writing possible is fraught with individuated decision-making. As Garfinkel suggests, we engage in any given social situation—whether it be arriving at the office for the twentieth year in a row, or being introduced to someone we’ve never met—we are always doing it “for another first time” (Studies 9). There is a newness, as well as a familiarity, to each language use, to each social construction. Our identification and response to this mix of the familiar and the new is where agency comes into play: we deploy our agentive powers as we (co)construct a social situation with other actors and tools, including writing.

Just as the people who (co)construct social situations have agency, the materials that are brought to bear on the (co)construction of those situations have an agency of their own as well. In order to make sense of Frank’s agency, I draw on the concept of symmetry, from the work of Bruno Latour and Michel Callon, among others, in their advancement of actor-network theory. Clay Spinuzzi defines symmetry as “the principle that human and nonhuman actants are treated alike when considering how controversies are settled” (23), and argues that this principle is, at heart, a methodological move. Drawing on a hypothetical example of bringing “undernourished hipsters” (24) and sound equipment together in an elevator with a specific weight limit at a SXSW festival, Spinuzzi demonstrates that, for very particular purposes (such as making sure an elevator does not get loaded past its capacity), it can make sense to treat humans and nonhumans as actors. Symmetry becomes “a methodological stance meant to get at some things and not at others” (27). By treating nonhuman actors as having agency, multiple facets of the (co)construction of a social situation are thrown into relief. Attention can be paid to the work that nonhuman actors do, if we imagine them to have the potential for agency to begin with.

In this particular study, symmetry highlights the role that writing plays in Frank’s life. Frank’s writing—and, in particular, his notebook practices—and my discussions about his writing reveal what appear to be widely-separated lifeworlds: artwork, religion, family, health concerns, and many other issues crop up that are not clearly interrelated. Symmetry, however, allows for me to follow not only people and language but also tools and objects. As I trace Frank’s literate practices across various aspects of his life, identifying the ongoing work of both humans and nonhumans to establish and perpetuate agency serves as an important sense-making research mechanism: it highlights the ongoing work that Frank needs to do to keep the spinning plates of his lifeworlds working together, and to keep himself operating on each of those spinning plates. In other words, a posthumanist approach to agency throws into relief the social and personal consequences of literate action by Frank.

Framing Agency: Chronotopes and Textual Coordination

Envisioning agency as circulating in the social construction of situations allows for researchers to follow the work of literate actors to construct and perpetuate agency through a range of means, with a range of tools, in incredibly different social settings. Looking for not just Frank’s writing but also how Frank’s writing contributes to the agency he perceives himself as having in any given situation sheds important light on Frank’s situational sense-making activity. But attending to the material, moment-to-moment work of literate action—as well as the ways in which it constructs and perpetuates agency—necessitates a close look at the nature of interpersonal relations: understanding the principles that drive ongoing, interpersonal work across a lifetime is the only way to establish useful concepts for envisioning agency and its relationship with literate action.

Various studies and scholars in sociology (Goffman; Garfinkel), interpersonal psychiatry (Sullivan) and sociocultural psychology (Vygotsky; Wertsch; Cole) have insisted for nearly a century that human identity is, at a fundamental level, interactionally constructed. Harry Stack Sullivan traces social action into the pre-language stages of human development, when the infant must coordinate with what Sullivan refers to as the mothering one (an anachronistic reference to one who feeds, changes, and otherwise takes care of the infant) in order to eat, remain clean, stay warm, etc. These pre-linguistic social actions carry within them the seeds of what will become the self-system of avoiding anxiety (Sullivan), the groundwork for the conscious socialization of gesture (Vygotsky), and many other important aspects of individual development into a social and cultural participant.

The socialized development of persons-in-action does not create cultural/ sociological/ judgmental dopes; rather, the series of unique interactions each individual encounters constructs rambling paths of social development that leads people to individuated understandings of society and social action that are also, to greater or lesser degrees, in tune with those around them. Many theorists from a variety of fields have gestured at the individuated understandings that emerge from this socialization process while tending to focus more on the social than the individual. Adam Smith, Alfred Schutz, and many others have mentioned the idiosyncratic differences among individuals, although for their particular fields of study, those differences were of little importance. Interpersonal psychiatry and sociocultural psychology are much the same way: Sullivan himself noted that “in psychiatry as a study of interpersonal relations, all these individual differences are much less important than are the lack of differences . . . the parallels in the manifestation of human life wherever it is found” (21). In the study of writing, however—and particularly in the study of writing in periods of intense transition, such as retirement—the idiosyncratic differences that are posited (though not attended to) in interpersonal understandings of human development become important. These aspects of writing are untypifiable—that is, they “fall away” (Bazerman 71) from our conscious attention while engaged in the intersubjective work of writing. While of minimal importance to psychiatry, sociology, and economics, however, these aspects are significant for understanding how individuals make sense of writing tasks, particularly across their lifespans.

In the study of individuals in limited times and places (a school setting, for instance), difficult-to-see idiosyncratic differences in understanding may mean little, depending on the particular research questions. But individuated understandings add up over a lifetime and can help researchers make sense of the particularities of the accumulated resources of older writers. When Frank reveals a passion for drawing and artwork, for instance, we can see the artistic aspects of his engineering career in a new light: the actor-oriented perspective of Frank’s literate life can be glimpsed, and the connection between his engineering career and his pursuit of new artistic techniques can be seen.

Understanding agency as socially constructed but individually enacted demands a set of theoretical constructs that enables both the social and the idiosyncratic to emerge in the pursuit of data. This study relies on two concepts to perform this feat: chronotopes (Prior; Prior and Shipka) and textual coordination (Slattery; Pigg). These concepts, when paired together in my later analysis, highlight both the lifeworlds Frank is involved in and his orchestration of those lifeworlds—the ways in which he worked with, through, and among them in his writing.

Paul Prior, Catherine Schryer, and Jody Shipka draw on Bakhtin’s use of chronotopes to understand the ways in which individuals organize their worlds for participation in literate activity. For Bakhtin, a chronotope is created within a novel. For Prior, Schryer, and Prior and Shipka, a chronotope is a place created by a writer and for a writer. The organization of activity, the flow of time, and the structure of a given space becomes structured for the production of, among other things, writing. As Prior and Shipka indicate in their study, chronotopes serve to orchestrate multiple streams of activity, allowing the creator of the chronotope to accomplish goals as necessary to continue to be an effective member of larger systems of literate activity. Chronotopes order, in other words, the world for the performance of writing and other associated tasks. But the connection between cognitive activity and social-material order is, as Edwin Hutchins and Bruno Latour indicate, two-way. Chronotopes order activity and material, but the activity and material that are chronotopically ordered also serve to tune and shape conscious attention.

Crucial for seeing the impact of chronotope construction on agency are instances of what Shaun Slattery refers to as “textual coordination” (“Understanding”). For Slattery, textual coordination “refers . . . to the selection of texts from a larger information environment and staging and manipulating them toward the production of a new text” (“Undistributing” 318). It is through acts of textual coordination that writing is “undistributed” into new texts, some of which rush out into the world. If chronotopes enable us to conceptualize the situations within which literate action is performed, textual coordination provides an object (that is, the chunks of distributed text) from that action which can carry into other social situations.

Chronotopes and textual coordination provide the framing concepts for envisioning agency as circulated in the ongoing production of social order. While work by Prior, Slattery, Stacey Pigg, and others has usefully demonstrated the effectiveness of these concepts at studying writing at all stages of the lifespan, they may be particularly useful when examining the work of those writing in later life. The literate lives of writers after their careers conclude are rife with possibility. Much of Frank’s writing life after retirement was shaped by a chance retirement gift from his sister, for instance, and identifying the impact of such a chance encounter requires attention to the material work of literate action that Frank engages in. The concepts of chronotope and textual coordination enable the tracing of literate action through whatever possibilities are realized by writers in later life. Such tracing also reveals the interconnected work of literate practices across a range of lifeworlds.

I met Frank, a retired engineer in his eighties, through a mutual acquaintance who ran a community writing class for older writers. Frank originally met with me as part of a larger study involving the literate lives of retired professionals who write on a regular basis. Frank’s literate practices proved so complex, however, that I asked him to meet with me further to discuss his literate practices and his published and unpublished writings. In total, I met with Frank for three interviews, each lasting between 75 and 120 minutes. During those interviews, Frank shared a number of texts with me, which I copied and analyzed as part of my emerging understanding of his literate life. In order to understand the relationship between Frank’s agency and his literate action, I examined first Frank’s literate life, then the construction of his chronotopes for writing, and finally the textual coordination that he engaged in.

My first interview with Frank was a literacy history interview, which I organized using Deborah Brandt’s interview framework (Literacy). Understanding Frank’s history as a writer allowed me to understand how the more specific information I would gather in later interviews was located in his overall experience with writing. This also provided a broad framework through which I could identify the broader themes developing throughout Frank’s life, such as his ongoing interest in artwork and faith, or his embrace of particular kinds of technology for writing. My second interview with Frank followed the picture-drawing interview protocol devised by Prior and Shipka. These interviews uncovered how Frank organized himself for writing, both in space and time. In his drawings and his articulations about those drawings, Frank demonstrated how he made use of his office space, the times of his day, and the ebb and flow of his lifeworlds to produce a wide range of publications, both personal and public, over a rather short period of time. My third interview with Frank focused on some of his recent publications—in particular, his publication of books on his Quaker faith and a collection of his artwork. We also discussed his journal writing, which is the grounds upon which much textual coordination occurs. I also used this interview as an opportunity to expand upon and clarify both Frank’s literacy history and his chronotope-constructing practices. The textual coordination served as a link between Frank’s broad literate life and the particularities of his chronotope construction.

The three interviews and their attendant documents provided me with a range of records from which I constructed units of data. Drawing on Brandt’s sociologically oriented approach to studying writing, I focused on mentions of writing that occurred in Frank’s interviews (“Studying”). That is, each mention of writing by Frank in his interviews was treated as a unit for further analysis. I organized these mentions of writing in the order that they occurred in the interviews (Roozen and Erickson), and drew from those mentions to construct a literacy history for Frank. I then isolated the mentions of writing that referred to the chronotopes for writing that Frank creates. With these isolated mentions to guide my study of Frank’s drawings, I developed an account of Frank’s chronotope construction. Through memo-writing, I then identified connections between Frank’s chronotope construction and the longer arc of his history as a literate participant in the world around him. These connections were used to identify potential instances of patterns in Frank’s literate action over a longer period of time, as well as connections to the lifeworlds that he inhabits. Using this interpretation of Frank’s interviews as a starting point, I re-read Frank’s texts, locating them in his literacy history and the development of his chronotopes for writing. Contextualizing his writing in this way indicates the larger lifeworlds that Frank’s writing contributes to. Connecting Frank’s writing to the larger lifeworlds he inhabited highlighted the ways in which Frank orchestrates his lifeworlds through his writing.

Frank’s use of textual coordination became a key element in understanding how Frank established and perpetuated his own agency through literate action: Frank’s literate action constructed textual objects that gained an agency of their own (Spinuzzi) as they became entangled with Frank’s various lifeworlds. The moments of textual coordination that Frank engages in highlight not only how agency is established in a given performance of literate action, but how those agentive moments build on one another, creating sustained lines of agentive action that stretch across Frank’s lifeworlds.

Findings

Frank’s Literacy History

In recounting his history as a literate participant, Frank identified a wide range of sponsors in his life. Friends, family, primary and secondary school, religious institutions, college, the military, graduate school, private enterprise, and the federal government shaped Frank’s engagement with literacy in one way or another across his life. In order to best understand the chronotope that Frank establishes in his writing during retirement—as well as the ways in which he repurposes his past practices for that writing—Frank’s literacy history can best be read by attending to two themes: his ongoing communication with his family and his developing expertise as a technical writer.

Although his schooling, military service, and later career took him to many different places around the world, Frank has been regularly in contact with many members of his family throughout his life. Perhaps the most significant interaction for Frank has been his communication with his mother. Frank’s mother is his hero. The two began exchanging letters when Frank left home to attend college. Frank and his mother would end up exchanging letters for the next forty-five years. After his retirement, Frank used the letters his mother sent him to construct a biography of her, which he self-published. Frank communicated with more family members than just his mother: he kept in contact with most of his siblings, and those contacts turned into opportunities for writing later in life as well. Frank also organized a collection of essays about their father (who passed away suddenly in 1957) and edited a book written by his sister-in-law. This collaborative book work later led Frank further into his local community, as he became more deeply involved with his religious community. In short, Frank’s family history, as amplified by his communication with his family throughout his life, became a recurring site of literate action that engendered other kinds of literate action.

The ongoing literate engagement that Frank’s family provided was deeply intertwined with his highly diversified and extremely successful career as an engineer. Frank received his BA in a highly competitive, five-year professional program in engineering at Ohio State University. Of the two-hundred-plus students who enrolled in the program with Frank in his first year, nineteen graduated. His success in this program led him to graduate school, the military, the private sector and, eventually, several teaching positions in the northeastern United States.

Frank saw himself as lucky in his career: “A lot of professors … will write ten or fifteen papers on the same subject, you know. Especially in the technical fields, maybe they’ll spend many years doing the same thing … and I was blessed with being able to get into lots of different problems, problem areas. So it was never boring.” Frank’s wide-ranging experiences, both in his time as a professor and while working for federally-funded laboratories, provided him with a wealth of experiences in doing various kinds of writing with various technologies, such as the Linux operating system and LaTeX typesetting. Frank’s experience with Linux and LaTeX, as well as his other publishing experiences, would prove an important tool for him as he developed his writing and publishing experience after retirement.

The Chronotope of the Commonplace Journal

The two themes of Frank’s literacy history that I outline above—his communication with family members and his developing expertise as a technical writer—were drawn on by Frank as he developed a journal writing practice after retirement. Frank’s sister gifted him with a copy of The Artist’s Way, by Julia Cameron, as a retirement gift in 1998 (Frank would end up pushing back his retirement to 2000). Frank was initially put off by the gift, but eventually began reading it and working from it:

In ’98 I looked at it—Why am I interested in this?—and I put it away. But I didn’t throw it away, because it was a gift from my sister. And so ten years later, in 2008, January, I looked at that and said well, I don’t know what I was thinking, but well I’ll take a look at it, you know? And so I went through the twelve weeks exercise with that book….You signed a contract with yourself that you would do it in good faith. And you had to write three pages every morning before breakfast, before you did anything in the day. And sometime during the week you had to take your artist’s self out for a date, to do something different than you’ve ever done before. And write about it in your book.

Frank’s interest in morning pages lasted well beyond the twelve weeks of the book. Drawing on this gift from a family member, Frank transformed the morning pages into an elaborate system of writing, revising, editing, and publishing volume after volume of writing on a daily basis.

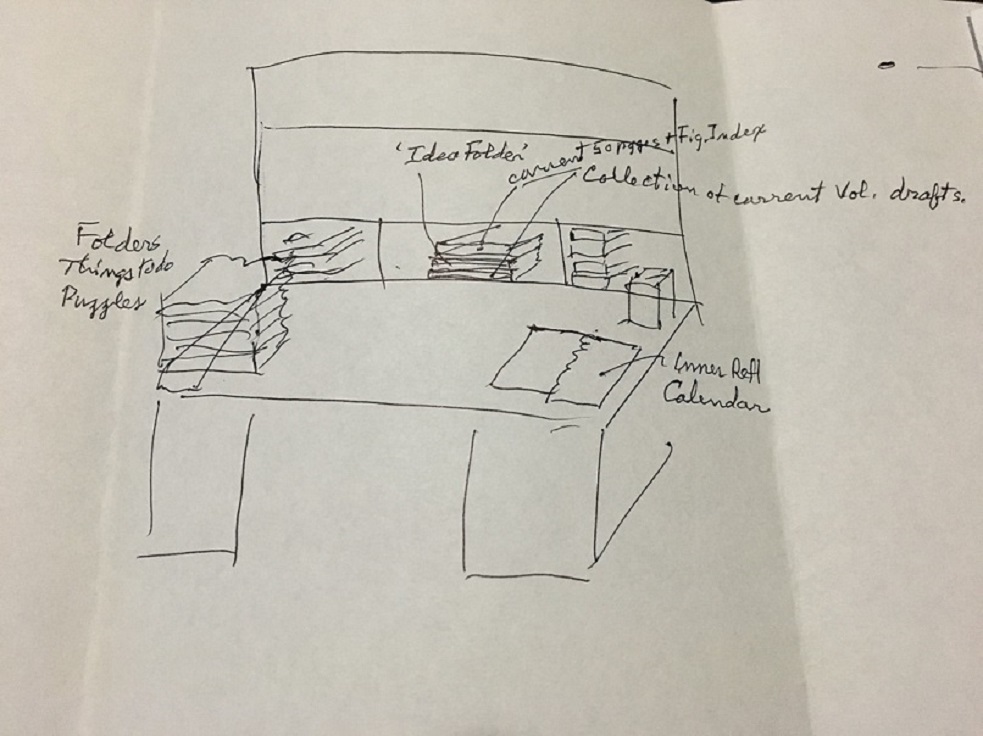

Fig. 1: Frank’s Drawing of His Home Office Writing Desk

Frank’s writing begins each morning when he wakes up. At a table depicted by Frank in Figure 1, Frank goes about writing his three daily pages. These pages offer a wide range of topics from many different facets of Frank’s life. Frank aims to write 133 days out of every five months. This translates to 399 handwritten pages every five months, which Frank then sends to a typist. The typist sends Frank a typed copy of his morning pages, which Frank then copyedits. Over the twenty years of his work on this process (Frank is currently on the twenty-second volume), Frank has developed a system that always has one volume being typed, one being copyedited, and one being written.

As seen by Figure 1, Frank has organized his writing space to facilitate three handwritten pages on a variety of topics every day—in other words, to enable a flow to his writing:

You know how you wake up in the morning sometimes and you’re coming out of a dream, and right at that moment it’s kind of vivid, but about two minutes later you can’t remember hardly anything about it? Well I can write these things, three pages in the morning before breakfast, from bed right down to the desk, I write it, and then when editing it after she’s typed it, I don’t remember writing that. So it’s certainly not conscious in some way, it’s called getting in the flow, and the thoughts just come. So it’s sort of dreamlike in a way, a lot of the time.

In this dreamlike state, Frank can move back and forth across a range of topics, from working on his novel (which follows the journey of a squirrel, Rodney), to issues of faith, to musings on health, family, and friends. Frank’s organization of his chronotope has allowed him to generate copious amounts of text on a daily basis in ways that interact with multiple lifeworlds—even if he does not remember much of the writing. In other words, although Frank might not be able to write so productively, Frank and the room can (Spinuzzi).

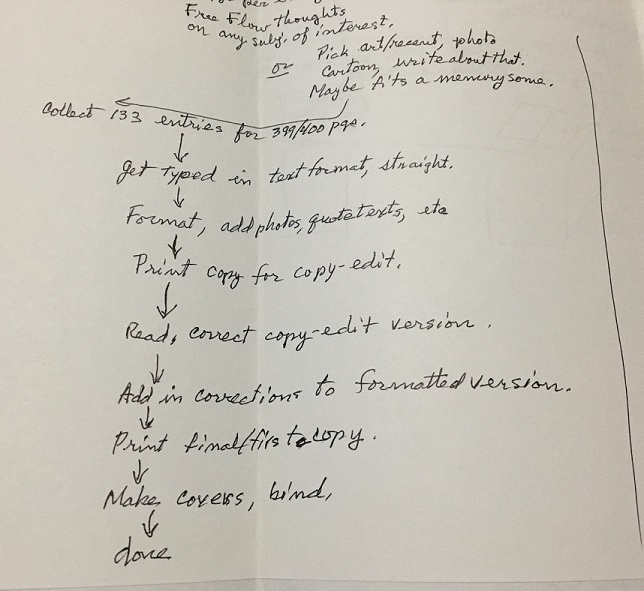

Fig. 2: Frank’s Production of Morning Pages

Frank’s morning pages regulate his communication with multiple lifeworlds in a number of ways. Most directly, they regulate his communication with his typist and the representatives of the publishing companies that he works with (Fig. 2). But the writing that Frank does in his morning pages regulates far more than Figure 2 identifies alone. In his morning pages, Frank makes lists of tasks for the day, works through decisions about how to deal with others in his life (notably, doctors), and reflects upon his feelings about particular life events—both current and long past. Just as Prior and Shipka found, Frank’s chronotope for writing his morning pages is deeply laminated: his production of the circumstances for what he calls writing flow is orchestrated via multiple streams of activity, as can be indicated by his shift from topic to topic across his pages.

Identifying and Tracing Expansive Agency: Three Instances of Textual Coordination

The immense work that Frank has done to establish a chronotope for writing, what Charles Bazerman refers to as courting the muse, has had enormous productive value in Frank’s life: he has produced a wide number of self-published books that reflect on his life, the lives of his family members, the institutions he belongs to, and the many projects (art, chess, music) that he has found himself interested in.

Through his literacy history and his chronotope construction, we can easily see how Frank’s literate action allows him to negotiate his lifeworlds. In my reading of Frank’s journals, however, I see evidence not only of the negotiation of those lifeworlds, but of the production and circulation of agency within those lifeworlds. When Frank engages with his journal writing, he is co-creating—with his journal, as well as his available artifacts in his chronotope—a social situation in which the power of language decisions flows through him. Frank’s chronotopic work creates a place apart from the social networks he is part of, and in that place, Frank can make language choices of his own accord and at times that suit him.

But Frank’s chronotopic work does more than simply give him the opportunity to write what he wishes. I suggest, based on my reading of Frank’s texts, that Frank uses the agency created in his journal writing to construct future social situations in other lifeworlds that will also allow agency to circulate through Frank. For instance, Frank might write out his thoughts on a given medical issue that he is struggling with, and this writing may clarify, for him, what he wants to say when he meets with his doctor.

Frank is not alone in this agentive work—by relying on the concept of symmetry, I can trace the ways in which Frank creates texts that also move (via textual coordination) from his journal writing into other social situations in the form of books. These objects work with Frank to circulate agency back to him in those future situations. I refer to this work of carrying agency beyond Frank’s journal-writing chronotope as expansive agency. Frank’s work to circulate agency through himself and his language choices in one situation creates understandings and objects that carry forward into future situations, allowing agency to continue to circulate back to Frank. Expansive agency is particularly clear in Frank’s work during moments of textual coordination. In order to demonstrate expansive agency at work, I present three moments of textual coordination: his faith, his emerging novel, and his artwork.

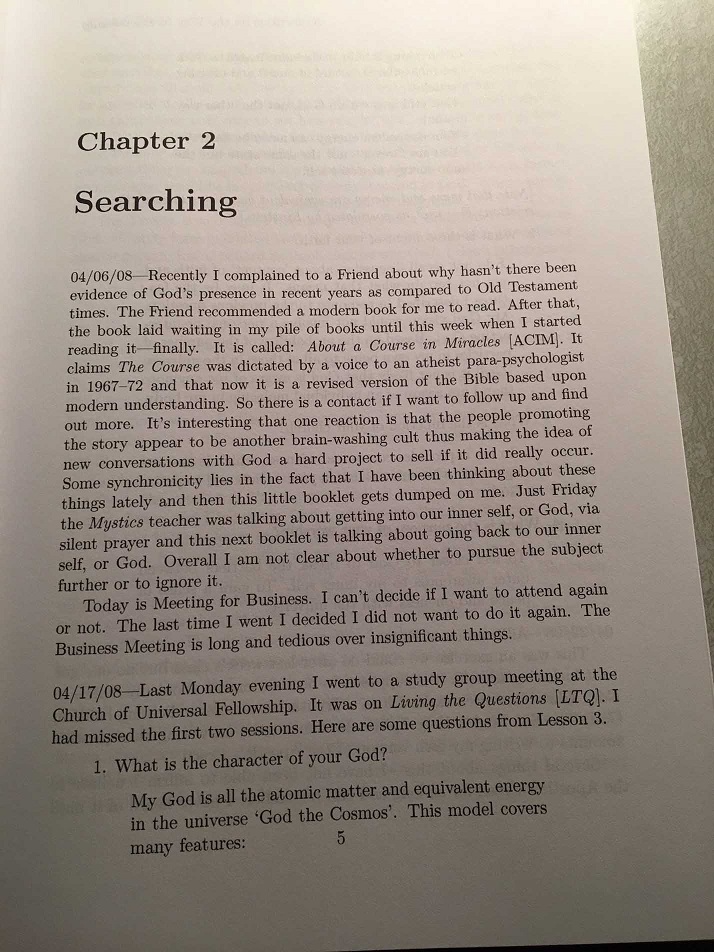

Frank’s interest in religion stretches back to his youth, but finally found a home in the Quaker faith later in life. A central feature of the Quaker faith is journaling, and so Frank’s morning pages fit in well with the faith that he has committed to. Frank regularly wrote about religion, mysticism, God, and faith in his morning pages, and eventually decided to pull that writing together into a text:

So last year, I went through all my things and I came up with this book. By going through and finding out discussions about my exploring the field of Quakerism and finding out if that’s a place for me and getting involved with Quakerism, so this is a prologue giving background, so now I’m searching in this phase, then I got involved, and then I arrived by becoming a member. And this is an epilogue to sort of make it final that it was a good decision to do. And I got all that text, almost all of this text out of the typed files by just word searching for Quaker [using his Linux program]. So I built a book from out of that.

Frank pulled directly from his morning pages to create a book that would serve as a useful instrument for those interested in exploring their faith. Frank believes the book is meant to be read a bit at a time, so that the reader has time to mull over each daily entry. This book is now available on Frank’s website, as well as the local library, and has been taken up by his local Quaker community to discuss their faith.

As can be seen from Figure 3, Frank’s topics range widely within each entry. The revisions that Frank undertook after bringing his text over from the morning pages has not changed that completely. What Frank has done in this instance, however, is continue a line of thought that began during a conversation with another Quaker (“Friend”). Frank’s concern about the lack of “evidence of God’s presence in recent years as compared to Old Testament times” has carried over into his morning pages, then into his book on faith, and from there into the sites that his book carries—Meetings with other Friends, conversations with those outside the Quaker faith who share an interest in the subject of religion, etc. Frank’s publication and distribution of his book, in other words, has provided him with the tools necessary to contribute to and shape conversations about faith within his Quaker community.

Fig. 3: An Instance of Textual Coordination in Frank’s Book on Faith

Frank uses textual coordination to similar ends via his emerging work on his novel, focused on a squirrel named Rodney. Since our first interview, Frank has expressed an interest in writing a novel. Writing about Rodney’s adventures has been Frank’s most recent attempt to complete a novel-length work. Frank lamented early on, to this author and others, about his struggles to make a novel come to fruition:

I really want to write a novel. And I haven’t figured out how to do that. I’ve written many premises for novels, they sound really interesting, to me, and I sit down to start to try to write it and I can’t seem to make myself do it, make up stuff, to make an interesting story that somebody would want to read.

Frank’s friends, former colleagues, and Friends have given him periodic advice on the matter. One friend was particularly blunt about the matter to Frank:

He said, hey, shit, Frank, it’s just work, you just go there and you write an hour every day… I sit down, I can’t make myself write anything. But I can write this stuff, you know, every day. That’s got him perplexed, that I can do this. I’m a writer, I think. I think it says I’m a writer. Or I want to write. And I write this, but I haven’t written a novel.

Frank’s identity, particularly early on in his post-retirement writing work, was not that of a writer. Through his morning pages, however—and, particularly, through the textually coordinated work that emerges from that writing—Frank has been able to slowly piece together a publication about Rodney and his adventures in and around the Penobscot River.

Frank’s textual coordination, in this case, has produced a situation wherein Frank can come to see himself—after however long a period of time, however haltingly, however uncertainly—as a writer. Just as Frank’s writings on faith enabled him to create the social situations that were co-constructed by his thoughts on the topics he had written about, Frank’s textual coordination here creates a social fact—his finished work on Rodney the squirrel—that allows him to more fully identify himself (and, by extension, be identified by others) as a writer. When friends and acquaintances encounter his books in the public library, on his website, in the university library, and around town, they then come to Frank with an understanding of his identity that he has struggled successfully create, and they support that identity in their co-construction of their interactions with Frank. In other words, Frank’s construction of an identity as a writer through his journal writing creates objects that circulate that identity in situations not directly involving Frank, which enable him to co-construct (for another first time) his writerly identity in future social situations with others.

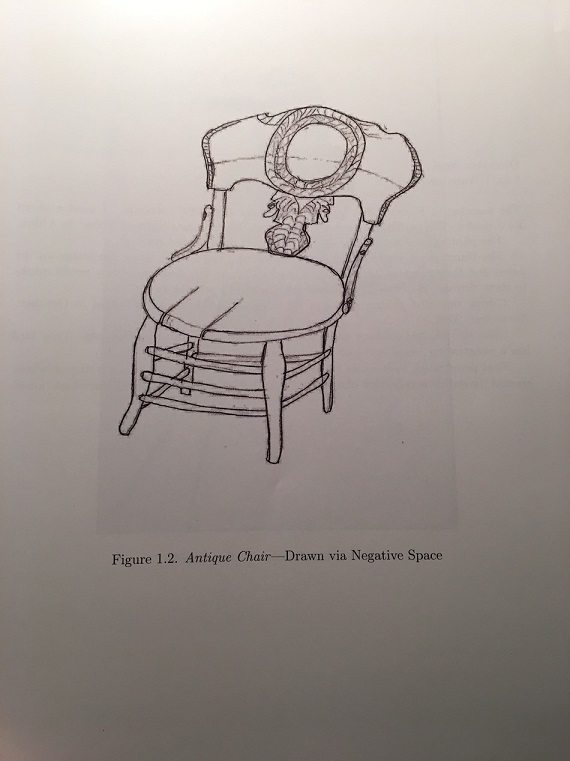

The final moment of textual coordination that I aim to show is based on Frank’s post-retirement life as an artist. Frank’s interest in drawing runs throughout his life, although this interest was repurposed into the field of engineering during his college years. After retirement, however, Frank took up drawing nearly as extensively as he took up writing, taking a wide range of art classes at a local university, as well as teaching himself other art forms when he wished. Frank wrote about his art regularly both on his website and in his morning pages. In 2017, he self-published a book chronicling his development as a writer from 2008 through 2017.

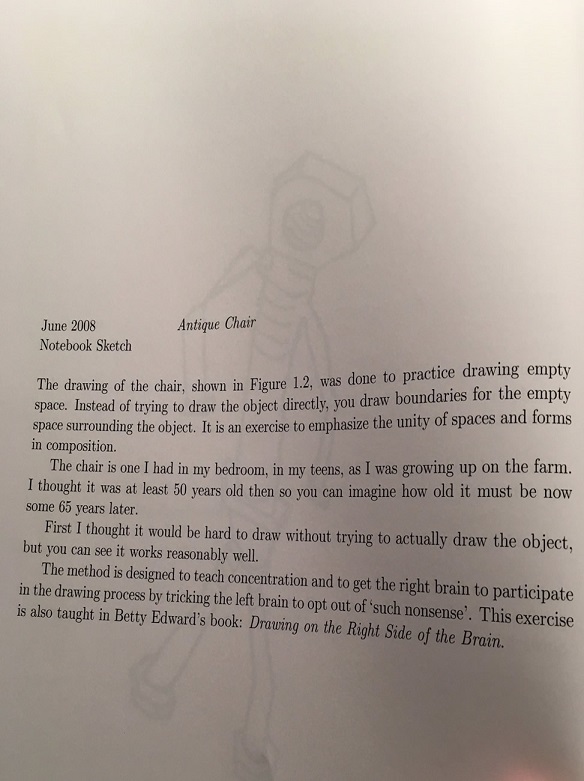

Fig. 4: An Antique Chair Drawing from Frank’s Artwork Text

Like his book on faith and his novel about Rodney, Frank’s book of art creates the conditions for him to further his agency in future social situations. Frank not only demonstrates a range of artistic experience, but also chronicles the development of that range. Figure 4, for instance, showcases his emerging work with negative space in mid-2008. In these drawings and the captions that accompany them, Frank locates the drawings in his own history (Fig. 5) and his wider understanding of art.

Fig. 5: Frank’s Caption for “Antique Chair” Drawing

Frank’s writings in this book build on the discussions of art in his morning pages, as well as the discussions on his website. The book draws across these artistic experiences (as well as the descriptions of those experiences) to continue to shape his understandings of and discussions about artwork and, in particular, his own artwork.

Frank’s artwork book (much like his publication on faith) has been made available via a local library and the university library, in addition to the copies that Frank has made for his friends and family. In much the same way that Frank’s other two books work, this text serves as an object that shapes the construction of social situations oriented toward art. Frank’s agency in shaping the discussion works in collaboration with the book, much as his book on Quaker faith supports and extends his agency in discussions with Friends.

The three moments of textual coordination presented here do more than simply carry writing from one setting to another; in doing so, they also carry on particular conversations, particular social scenes, that enable Frank to continue to be an active participant in those scenes. Frank’s sociohistoric engagement with the talk, tools, and texts around him allow him to build social situations that continually circulate agency, in one shape or form, through him.

I have attempted, in the moments of textual coordination above, to demonstrate the expansive agency that Frank’s literate action has generated in his post-retirement life. By extending the social situations within which agency circulated through him, and producing objects that support the re-circulation of agency to Frank in future situations, Frank was able to expand his agentive power across time, space, and lifeworlds. Frank’s displays of expansive agency offer multiple insights for research on the literate action of writers in later life.

One of the key issues of understanding aging in contemporary society is understanding the role that agency plays in it: how do older members of society gain, lose, and revise their agentive powers? Frank has demonstrated, through his acts of textual coordination, that agency can be taken up in moments of engaging with language for another first time, and that such take-ups of agency can be compounded, built upon, and used to transform future social situations across multiple lifeworlds in order to create expanding agency over time. Understanding agency as circulated in social situations, and as being a capability of human and nonhuman actors alike has uncovered an important aspect of agency in old age. As people age, their agency is part of the chains of social situations that they participate in. Framing Frank’s agency as something possessed entirely by him obscures the complex, situational work that he does to establish, maintain, and further agency over time. But if we see Frank as being in situations where agency circulates through him, and if we see Frank taking these moments of positive agency circulation to develop future situations where this agency will persist (and, indeed, expand), then a number of options for preserving the agency of older members of society arises.

Frank’s morning pages enable him to be an active member in a wide number of lifeworlds. Within his morning pages, these lifeworlds become laminated: Frank moves among them at will, in the “flow” of his writing. This juxtaposing of lifeworlds with one another, this ability to toggle back and forth among various ideas, thoughts, concerns, and attentions, allows Frank to develop new perspectives on those lifeworlds—and, along with that, the space to develop those new perspectives, continuing the chain of earlier social situations that can lead Frank to different forms of social action. By creating a space for Frank’s lifeworlds to come together, the morning pages both continue the social situations that allowed Frank to establish agency and give Frank the opportunity to reach new insights along the way.

Not all older adult writers will have some of the opportunities that Frank has: they might not have the technological prowess to create “camera-ready copy” of their writing; they might not have the time and resources to devote to the wide range of lifeworlds that Frank participates in; and they might not have the flexibility in their schedules to construct daily morning pages as steadily as Frank has for the past two decades. But the specifics of Frank’s morning pages are less important than the general claims that emerge from them. Considering how literate action can be used to circulate agency back to oneself in future social situations, and how that circulation can be sustained over extended periods of time (i.e., across multiple situations), can dramatically transform the ways in which we encourage and support agency in the older members of our population.

Suggestions for Further Research

At the heart of the peculiarities of Frank’s situation is the issue of time: Frank had considerably more control over his schedule than other older writers might. Some older writers need to pick up other jobs, or shoulder considerable family responsibilities, or have to work with and around significant health concerns. The impact of these variables on older writers’ ability to expand their agency across situations is an open question, and a close examination of expansive agency (or the lack thereof) across multiple cases may yield important information about the complex social actions that enable the circulation, perpetuation, and expansion of agency. Further research on the literate lives of older writers, then, may begin by attending to time—amount available, control over it, opportunities to write in given segments of it—in order to capture the wide-ranging literate lives that older writers are living in contemporary society.

Expansive agency as a concept may also be useful for the study of other populations. While tracing the agency-supporting work of writing is particularly important for older adults, the work that literacy does for Frank in this case study suggests that exploring the agentive work of literate action at other points in the lifespan may be useful for understanding the individuated, richly literate lives of writers. Though Frank does offer a perspicuous setting for the study of agency through literate action, and has a wide range of resources for constructing, supporting, and perpetuating his own agency thanks to a lifetime of experience, the work that he does to construct his agency is rooted in the everyday interactional work that human beings perform throughout their lives. Further research could explore the work of writers to construct, support, and perpetuate agency at other ages and in other circumstances. These future settings might be less perspicuous than Frank’s, and may require the development of new methods to successfully trace agency-supporting work, which could, in turn, be used to develop a more complex understanding of the agentive work that literate action performs for older writers as well.