Abstract

This article, based on an ethnographic study of aging among women, reports on the benefits of literacy across the lifespan. Using methods based on phenomenological human science, I selected four participants in their eighties and nineties from a small town in Western Massachusetts whom I regarded as exemplars of positive aging. The importance of reading and writing over a lifetime emerged as a central theme in helping to explain how these women coped with the challenges of aging. In the participants’ elder years, literate activities were particularly significant as a way of constructing meaning. With illustrations drawn from the women’s literacy experiences over the better part of a century, I focus on the importance of early literacy development, the key role of literacy sponsors, the self-sponsored nature of memorable literacy experiences, and the differing ways in which the women used reading and writing in their adult years. All four expressed alienation from computers and modern communication technology. Despite this limitation, however, literate activities remained central into old age, helping them to make meaning of their lives, a crucial developmental task in old age. For the women in this study, active, lifelong literacy was a key factor in their continued vitality and involvement in the elder years. |

Keywords: aging; aging well; literacy; lifespan; life course; life history; meaning

Contents

The Importance of Early Literacy

Literacy as a Lifelong Narrative

Making Meaning Across the Lifespan

Introduction

“What people are able to do with their writing or reading in any time and place—as well as what others do to them with their writing and reading—contribute to their sense of identity, normality, possibility.” (Brandt, Literacy 11)

In this article I report the findings of a small-scale, ethnographic study of positive aging in women. A major theme1 that emerged from interviews with my four participants, women in their eighties and nineties, is that a lifelong engagement with reading and writing was an important key to aging well, a vital part of who they were and what they could hope to achieve at all stages of life. Reading and writing were of particular significance in the elder years as a way of making meaning of one’s life. For these women—and many others—literacy is important not only for the value these “skills” can earn in the marketplace but for the life-enhancing benefits that come to individuals who maintain an active engagement with literacy throughout their lives.

Existing scholarship on literate development usually focuses on a short time span. Even studies described as longitudinal often deal with only a few years of the students’ college careers (Beaufort; Carroll; Herrington and Curtis; Sternglass). However, the literacy described in such studies began long before these students entered college and continued for many years after graduation. What happened in the earliest years to make these students the readers and writers they became? And what meaning did the literacy they worked so hard to achieve during the college years have in their later lives? Specifically, what role did literacy, initially acquired in childhood, play toward the end of life?

By looking closely at the literate lives of individuals from childhood through old age, much can be learned. From this perspective, the four women in my study of aging have a great deal to teach us about the role of literacy over a lifetime. My study espouses an ecological view of literate development (Syverson), a model that “understands an individual’s writing abilities as developing across an expansive network that links together a broad range of literate experiences over lengthy periods of time” (Wardle and Roozen 108). Such an approach addresses Paul Prior’s critique of the 2017 multi-authored forum article in Research in the Teaching of English, “Taking the Long View on Writing Development” (Bazerman et al.). Prior argues that the view articulated in this article mistakenly assumes that most writing development takes place as a result of school activities (216-17) and can be studied separately from other aspects of literacy development (213-16). Instead, in Prior’s view, “research on the lifespan development of writing needs to begin with embodied, mediated, dialogic semiotic practice as its unit of analysis and to trace what people do, learn, and become across all the deeply entangled domains of their lives” (211). By attending to the participants’ literacy experiences from early childhood through old age, in school and (mostly) out of school, my study examines how these experiences are deeply entwined with who they were and who they have become.

One purpose of this project is archival, describing literacy experiences that occurred over the better part of a century. Using “thick description” (Geertz), I hope to show the ways in which the literacy that the women began to develop in childhood has played out as part of a lifelong narrative. In the pages that follow, I will focus on the importance of early literacy development, the self-sponsored nature of memorable literacy experiences (Gere; Roozen), and the differing ways in which the women used reading and writing in their adult years. Not surprisingly, certain generational trends were apparent. For example, all four spoke of their discomfort with computers and modern communication technology, a new literacy they chose not to embrace. Despite this limitation, however, literate activities remained central to their lives into old age, helping them to cope with the challenges of aging in positive, life-affirming ways. The women’s facility with reading and writing provided a way to make meaning of their lives, a key developmental task in old age (Cohen; Edmondson; Erikson, Erikson, and Kivnick).2 Taking the long view of literacy as acquired and practiced over a lifetime is extremely important in assessing the uses of literacy in old age. Nurtured in childhood, developed during adulthood, it can and often does become a source of meaning and connection at a time of life that is challenging, even for the most fortunate. For the women in my study, their active, lifelong literacy was a key factor in their continued vitality and involvement in the elder years.

Overview of the Study

In the mid-2000s, contemplating the world’s rapidly aging population, I asked myself: What is society doing to prepare for this huge and rapid demographic shift? And what can we as individuals do to make the elder years more meaningful and enjoyable for ourselves? Having used qualitative, interview-based methods for my doctoral dissertation and subsequent book (Mlynarczyk, Conversations), I was convinced that much could be learned from small-scale studies of a few individuals. Using purposeful sampling (Palinkas et al.), I selected four women from Plainfield, a small town in the hills of western Massachusetts where I have been spending summers and weekends since 1973. Despite their advanced ages, these women were still vitally involved in living. For me, they were—and still are—positive models of what it could mean to grow old.

When I began this study, I often described it as focusing on “successful aging.” At the time I was not aware of the controversy surrounding this term. In their book Successful Aging, based on a ten-year study by the MacArthur Foundation, John Rowe and Robert Kahn attempt to counter the widely held notion that old age is characterized primarily by decline and disease. As many scholars have subsequently pointed out, however, this account vastly oversimplifies the complex phenomenon of aging (see, for example, Cruikshank; Katz and Calasanti). Rowe and Kahn promote the view that individuals can improve the odds for “successful aging” through diet and exercise, educational attainment and cognitive stimulation, and social interaction. Critics of the “successful aging” model equate this view with a white, male, neoliberal perspective, one that emphasizes “productivity” and individual effort while ignoring the crucial roles that race, class, gender, and broad socio-political factors play in one’s ability to age successfully according to this definition. They point out as well that focusing on “successful agers” necessarily implies the widespread existence of many who, through factors beyond their control, are “unsuccessful agers.”

In April 2018, I arranged to talk with the two surviving participants, Anna and Blanche, and we discussed the controversy over the term “successful aging.” Blanche had strong feelings about this issue: “It irks me a little when you see a commercial on TV asking, ‘Are you ready for retirement?’ And it shows young-looking people playing tennis or traveling to Europe. Well, that’s just not possible for many people.” She went on to say, “You can’t put a pattern on successful aging or successful retirement. A lot of it is just being satisfied with where you are.”

I have come to share these concerns about the implications of “successful aging” and no longer use the term to describe the women in my study. Instead, I refer to “vital involvement in old age,” “aging well,” or “positive aging.” Whatever term is used to describe them, it is important to acknowledge that these women, like everyone who lives long enough to become one of “the oldest old” (age eighty-five or older), will not remain forever free of disability, disease, or cognitive decline. Rather, their “success” lies in the ways they respond to the challenges that inevitably come with aging as a woman in twenty-first-century America.

When I began this study in 2007, I explained the project to the women and submitted IRB (Institutional Review Board) forms. They chose to have their real names used rather than pseudonyms. Allow me to introduce them.

The oldest participant, Mary Kathryn (Kay) Dilger Metcalfe, was born in 1912 in Clarksburg, West Virginia. After graduating from high school, she attended the College of Wooster in Ohio and later graduated from the Parsons School of Design in New York City. In 1934, as part of a Parsons-sponsored study abroad program, she traveled to Paris to continue her art studies, an experience that changed her life, not only by furthering her artistic development but also by sparking a lifelong fascination with history. After graduation, she worked for a few years as a designer before her marriage in 1938. The mother of two children, she re-entered the workforce after her children left for college, designing visual displays for the local public library. When I interviewed Kay in 2007, she was ninety-four years old. Since that time, Kay continued to live at home with help from her daughter, who lived with her. In old age, Kay experienced severe hearing loss, and after her hundredth birthday, she rarely left the house, spending her last years mostly in bed but still welcoming visits from friends and family. She passed away peacefully on February 21, 2018, at the age of 105.

Irene Jordan Caplan was born in 1919 in Birmingham, Alabama. The child of musical parents, Irene earned a bachelor’s degree in voice performance at Judson College in Alabama and then moved to New York City in 1940 to pursue a career in opera. In 1946 she was offered a three-year contract at the Metropolitan Opera and performed major roles with the company as a mezzo-soprano from 1946 to 1948. In 1947 she married a violinist in the opera company’s orchestra, and the couple had four children. After retraining as a soprano, she resumed her career in 1951 and continued to sing and teach professionally for many years. Irene was eighty-eight years old when I interviewed her in 2007. Shortly after these interviews, because of physical and cognitive problems, she moved to an assisted living facility and then to a nearby nursing home. Although she suffered from serious dementia in her final years, Irene kept her warm smile and outgoing personality. She died in 2016 at age ninety-seven.

Blanche Svoboda Cizek was born in 1919 in New York City, the child of Czech immigrant parents. She studied piano for many years, beginning at age eight, and often accompanied school performances. She attended Julia Richman High School, an all-girls school in Manhattan. After graduating, she worked for two years as a payroll accountant. She married in 1940 and had two children. Although Blanche did not work outside the home after her sons were born, she assumed a leadership role in a number of civic and religious organizations. She was eighty-eight years old at the time of our interviews. In spring 2016, Blanche underwent major surgery and spent several months in the hospital. Later that year, she returned to her home in Plainfield, where she lives alone with occasional help from friends and relatives. Blanche celebrated her ninety-ninth birthday on March 10, 2018.

Anna Rice Hathaway was born in Plainfield in 1929, the only participant who was born in town (the others are “transplants,” who first spent summers and weekends in town and later retired there). She attended the local one-room elementary school and graduated from high school in a neighboring town. She married a local man in 1948, and they had four children. Over the years Anna has held a number of official positions in the town. Now, in 2018, she is eighty-nine years old and lives alone at her home in Plainfield.

Like myself, all these women are white and middle-class. All are members of the Plainfield Congregational Church, which is where I initially came to know them. I decided to limit this study to women’s experiences of aging for several reasons. The majority of people in the age group known as “the oldest old” are women. In the 2010 US census, 67% of people eighty-five or older were women, a gender gap that steadily increases with age. Women were also more likely to be dealing with the challenges of aging on their own. In 2010 only 18% of women over eighty-five were married, compared with 58% of men. Among this group, 73% of women were widowed compared with 35% of men (“Population: Number of Older Americans”). All the women in my study were widowed. Finally, women’s experiences, especially among this age group, are not usually part of the public historical record. My project was designed to honor the life experiences of these women and preserve their stories of positive aging.

Goals and Methods

The design and implementation of this study were based on the phenomenological human science described by Max van Manen in Researching Lived Experience:

From a phenomenological point of view, to do research is always to question the way we experience the world, to want to know the world in which we live as human beings. And since to know the world is profoundly to be in the world in a certain way, the act of researching—questioning—theorizing is the intentional act of attaching ourselves to the world, to become more fully part of it . . . . (5)

In van Manen’s view, this type of research is a caring act: “we want to know that which is most essential to being” (5).

My goals and methods were very different from those of the study of successful aging described by Rowe and Kahn. In critiquing this study, Margaret Cruikshank observes, “research in a positivist spirit” will not be able to account for many factors that play into one’s experience of aging, “factors that may be elusive, changing, or knowable only by intuition” (2-3). The need to attend to such “subjective” factors was confirmed in 2011, when The Gerontologist, a major journal in the field of gerontology, expanded its scope by welcoming contributions from the arts and humanities. Introducing this new policy, editors Helen Kivnick and Rachel Pruchno encouraged scholars to submit articles based on research, often qualitative in nature, that focus on “meaning and interconnection, not on prediction or explanation as does empirical research” (142). Such studies are valuable “in the exploration of aging as it is portrayed, understood, and/or experienced” (142).

This meaning-based approach to age studies has gained traction in recent years and provides the basis for the interdisciplinary work of Ricca Edmondson, a scholar interested in creating a “wisdom-related discourse” (1) focusing on small-scale behaviors of ordinary people: “Openness . . . of this kind could concentrate attentiveness to what older people do and say, emphasising that the meanings they have to offer are potentially illuminating not for them alone, but for everyone” (2). Yet, surprisingly, in scholarship that focuses on the importance of meaning in aging, very little attention has been paid to literacy, particularly reading and writing, as a way of creating meaning throughout the lifespan (see, for example, Edmondson; Erikson, Erikson, and Kivnick). In this article, I take a small step toward correcting this neglect.3

The goal of my study was to learn what had enabled these women to remain so vital and involved in living in their elder years. To address this broad research question, I conducted a series of open-ended, qualitative interviews (Seidman) with each woman focused on three life periods: childhood, adulthood up until the deaths of their husbands,4 and old age. During these interviews, I practiced the feminist rhetorical practice of “deep listening” as described by Gesa Kirsch and Jacqueline Jones Royster (649). Like van Manen and Cruikshank, Kirsch and Royster value reflection, intuition, care, and listening as essential to understanding social phenomena.

I personally transcribed the interviews, listening and relistening to the women’s voices and their words, and coding the transcripts for major themes that recurred. I also collected writings done by two of the participants (Kay and Irene) over many years of their lives. As the study progressed, I asked the women to read and comment on my written reports, and we met several times as a group to talk about the findings. I have given several public presentations about this research, and reports on the project are available on the website of the Plainfield Historical Society (Mlynarczyk, “Coming of Age”). In April 2018, I scheduled a conversation with the two surviving participants to discuss my emerging findings about literacy across the lifespan and check for accuracy, a qualitative research practice known as member checking (Creswell and Miller).

There are certain limitations to this research, which need to be acknowledged. First is the small sample size. Of course, it is not possible to make sweeping generalizations about the lifelong value of reading and writing based on the experiences of only four participants. What we can gain from small-scale, qualitative studies such as this are portraits of the value of literacy for these particular women, case studies that can serve as the basis for comparison and contrast as more information emerges. Elliot Eisner describes the kind of knowledge generated by such studies:

Research studies, even in related areas in the same field, create their own interpretive universe. Connections have to be built by readers, who must also make generalizations by analogy and extrapolation, not by a water-tight logic applied to a common language. Problems in the social sciences are more complex than putting the pieces of a puzzle together to create a single, unified picture. (210)

Another limitation is that the original study (and the interviews conducted in 2007) were focused on aging well, not on literacy development. Thus, I didn’t probe as deeply about matters of reading and writing as I would have if that had been my primary focus. What is noteworthy, however, is that each woman, as she looked back on her life, described literacy experiences as having been extremely important. Beginning in early childhood and continuing through old age, literacy was a way of exercising agency, a way of taking control of situations that might otherwise be outside their control. This type of control becomes increasingly important in the elder years.

The Importance of Early Literacy

In planning for the interviews, I decided to start by focusing on the women’s childhoods. I felt it would not be wise to try to understand who these women had become in their later years without first finding out who they had been as little girls.

All the women had been born into families that encouraged their literate development. Anna’s mother (born in 1894) had been an elementary teacher before her forced “retirement.” Married women were not allowed to teach in those days. She continued to teach unofficially, however, reading to her own children and transmitting her love of stories and appreciation for the humor one could find in literature. Anna spoke warmly of listening to her mother reading aloud from the Pooh books by A. A. Milne and the “Just So Stories” of Kipling, books that Anna read to her own children years later. The original copies still exist and are regarded as valuable family heirlooms.

Blanche, too, was raised in a family that valued literacy. Her parents immigrated to the United States in 1904 from what is now the Czech Republic. They were busy earning a living in the new country, but literacy was an important part of their lives. Although Blanche and her brother had been born in New York City, their father insisted that they speak Czech at home. The arts were important in this household. Her mother performed in a Czech theater group, and both parents sang in a choir that performed in venues around the city. One of Blanche’s early memories is watching her mother moving around the apartment, dusting the furniture with one hand while holding the text of a play in the other hand, practicing her lines.

Reading and writing were also important for Kay and Irene as they were growing up. Both mentioned that, from an early age, they had been fascinated by language. Thinking back on her childhood, Kay explained: “I was terribly interested in words. And even from junior high school I had a little booklet, one of those black and white books. I would write things that I liked, copy things that I liked there. I’ve done that ever since then.”

Irene was eager to describe her own early literacy development. She vividly recalled memories of teaching herself to read at the age of three with the help of a Chautauqua desk, an early twentieth-century educational “toy” based on the principles of Maria Montessori and readily available by mail order: “It was the joy of my life when I was a very [spoken with emphasis]young child.” After describing the desk in great detail, she continued:

One night the family was sitting around in front of the fireplace. . . . And Mother and Daddy said, “What is she saying?” I was sitting on the floor, and there was a piece of newspaper open on the floor, and I was saying, “5 C puh ging ham.” And they kept saying, “What is she saying?” And they looked down and saw that it was “5 cents per yard. Gingham.”

This young girl was fortunate to live in a family where literacy was celebrated. Irene and her older sister soon began to promote literacy themselves among other children who lived nearby: “We felt like it was our mission to teach the neighborhood. We had a little school in our yard. We had an alarm clock and would set that for the ringing of the bell [between periods].” The results of this little school were sometimes dramatic. Irene recalled: “One of the mothers came and thanked us because her son had been double promoted when he got back to school in the fall.”

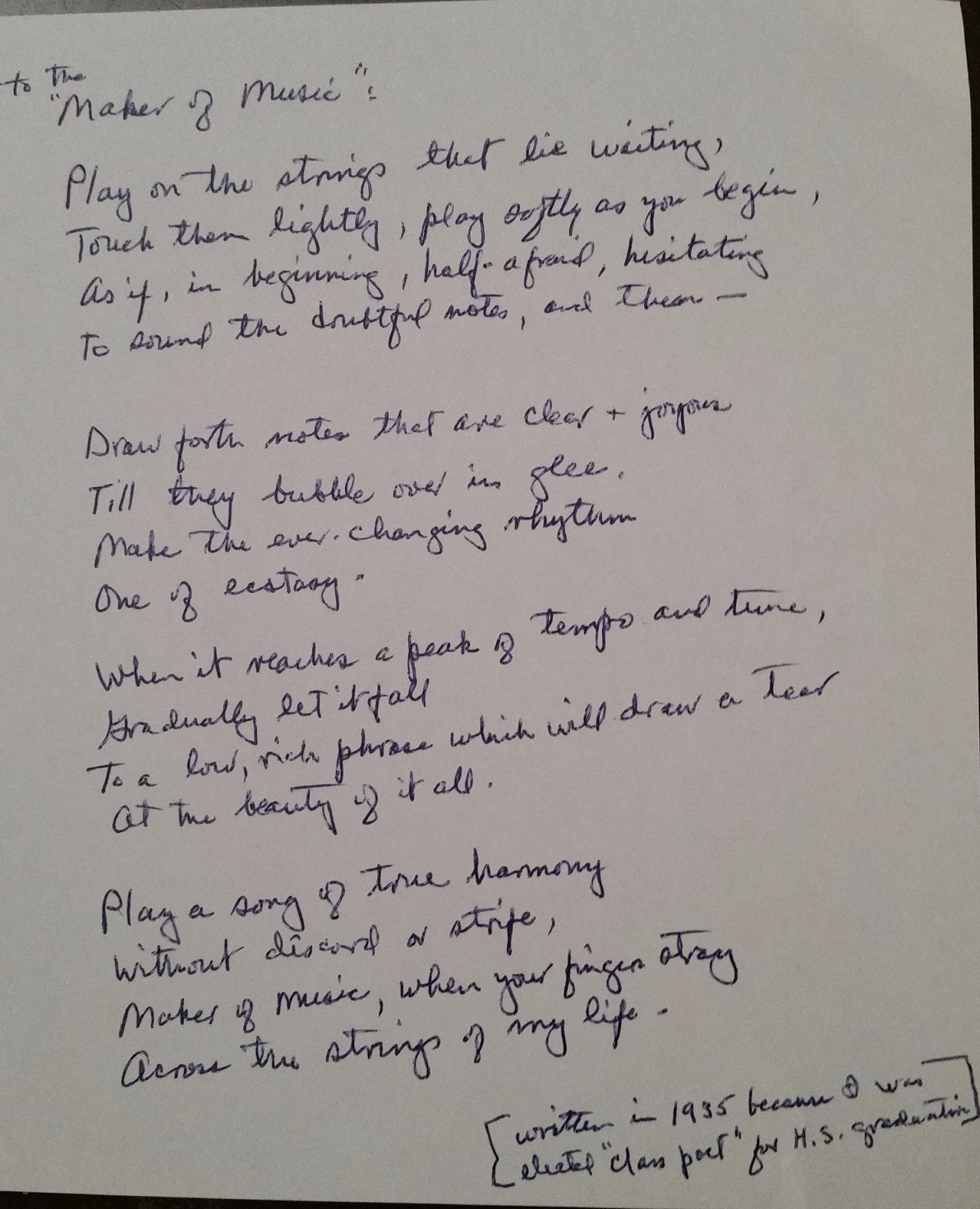

When it was time for Irene to start school herself at age six, the school authorities decided she should skip two grades, beginning in grade three. Looking back, Irene felt this was a mistake for her social development (her classmates and teachers often referred to her as “the baby”). However, she had no trouble keeping up academically, and her facility with language continued to flourish. When she graduated from high school in 1935 at age sixteen, her peers elected her “class poet.” The following excerpt from her graduation poem, entitled “To the Maker of Music,” aptly described what was so distinctive about her own singing much later in her life.5

Draw forth notes that are clear & joyous

Till they bubble over in glee,

Make the ever-changing rhythm

One of ecstasy.When it reaches a peak of tempo and time,

Gradually let it fall

To a low, rich phrase which will draw a tear

At the beauty of it all.

Fig. 1: Irene’s “To the ‘Maker of Music’” poem, originally written in 1935

The early literacy described by the women in my study had many benefits, some of which did not become apparent until years later. For one thing, their childhood involvement with reading and writing may be helping them to delay cognitive decline in old age. There is accumulating evidence of the cognitive benefits of literacy, not only during the school years but stretching into old age. The so-called Nun Study, which was designed by David A. Snowdon, an epidemiologist and professor of neurology, to learn more about the factors involved in Alzheimer’s disease, has shown a link between early literacy and improved mental functioning many years later. The cognitive condition of the 678 nuns in the study has been assessed regularly, beginning in 1986, and findings from the study have been reported in numerous medical journals (see, for example, Snowdon; Riley et al.; Snowdon et al.).

In addition to the medical data available to researchers, there is verbal data as well: the autobiographical essays the young women wrote before taking their vows. Ninety-three of these autobiographies (written at an average age of twenty-two) were selected for analysis. Susan Kemper, a psycholinguist experienced in studying the effect of aging on language skills, developed a system to analyze the autobiographies for “idea density” and “grammatical complexity” (Snowdon 109). Kemper and her team were not told anything about the participants’ current cognitive condition. After the early writing was coded for idea density and grammatical complexity, both factors proved to be statistically significant predictors of current positive cognitive status, with idea density showing a stronger relationship. This connection did not seem to be influenced by the nuns’ educational level or occupation. Commenting on this finding, Snowdon expressed surprise: “Somehow a one-page writing sample could, fifty-eight years after pen was put to paper, strongly predict who would have cognitive problems” (112-13).

As I have read and analyzed the interview transcripts of the women in my study, I have been impressed by the sophistication of their vocabularies and the complexity of their ideas. The little girls who were fascinated with the power of language have matured into women for whom language matters a great deal. Perhaps their verbal facility has also helped to delay cognitive decline.

Literacy does not occur in a vacuum. As young girls, Kay, Irene, Blanche, and Anna internalized the beliefs of those in their immediate social and familial worlds. The message was clear: reading and writing were an important part of being a successful person. Far from being only a set of skills, literacy represented values that were passed down in—and mostly out of—school. As Anna put it, “Everybody read.” For these women, the literacies that were encouraged in their early years aligned closely with the literacies practiced and rewarded in school. Kay, who, as a young girl, began to keep a notebook of memorable quotations. Irene, who along with her older sister, started a school for the neighborhood children. Blanche, who watched her mother with a book in one hand as she dusted the furniture with the other. And Anna, whose mother created a kind of home school for her own children after she was forced to give up her teaching career. Clearly, too, all four had certain inborn cognitive qualities that equipped them to benefit from the literacy opportunities available to them. None of them had learning disabilities that would have made learning to read or write unduly difficult. And fortunately for them, these were ways of being in the world that lasted into old age. At the time of our interviews, all of the women were still able to engage actively with reading and writing.

In February 2011, three of the women gathered in my kitchen to talk about literacy; Irene was not able to join us. These links to video clips from the session give a sense of the women’s personalities and the different ways in which literacy was important in their lives. Kay, age 98 at this time, talked about her lifelong fascination with words. Blanche, age 91, talked about the mysteries of brain functioning and about how her own literacy might have been fostered by her study of the piano and her bilingualism. And Anna, who is known for her good memory and wry sense of humor, recited several limericks as examples of literacy.

Kay, age 98

Blanche, age 91

Anna, age 81

Looking back, we see that, for these women, literacy is part of a lifelong narrative. As they grew older, they used reading and writing as resources to enrich their lives in ways that directly related to the habits and values established in childhood and practiced over a lifetime. In this section, I will look again at each of the women and identify literacy themes that have run throughout their lives and that help to explain how reading and writing have been powerful influences on their ability to age well.

Literacy Within Community: Anna and Blanche

For Anna, a theme that runs throughout her literacy narrative is the key role of literacy sponsors. Defined by Deborah Brandt as “any agents, local or distant, concrete or abstract, who enable, support, teach, model, as well as recruit, regulate, suppress, or withhold literacy—and gain advantage by it in some way” (“Sponsors” 166), literacy sponsors have been especially important influences in Anna’s life. As the only one of the women who was born and raised in Plainfield, Anna had limited opportunities for advancement in this rural community. Female literacy sponsors were instrumental in her selection for various positions, both paid and unpaid, within the town.

The earliest and most influential of these literacy sponsors was her mother. Forced to retire from teaching because of her marriage, Anna’s mother eagerly embraced the role of literacy sponsor for her children. Another significant literacy sponsor was her Sunday school teacher from the age of three onward, a woman who also served as the town librarian for many years. Anna worked under this woman’s tutelage as assistant librarian, and when she died at the library desk at the age of ninety-seven, she had made it clear to the authorities in Boston that Anna should be her successor. A few years later, when the town postmaster decided to retire, she too had designated her assistant, Anna, to be her replacement.

As Brandt’s research on literacy sponsors has demonstrated, literacy helped many people in the twentieth century to improve their economic and social status, and this has definitely been true for Anna. However, her life has also been enriched in other, intangible ways by her love of reading and writing. Now, in retirement, Anna has become an important literacy sponsor herself. As treasurer and official distributor of the Plainfield Post, she assures that this biweekly newsletter, an essential source of town news (even in this digital age), is never late to arrive in residents’ mailboxes. As a retired librarian, she is always on the lookout for books and articles that might be of interest to others and has an almost uncanny knack for knowing who would be interested in reading what. She is often seen at town events with a book or magazine in her hands, ready to pass it on to the right person. As if to demonstrate her continuing role as literacy sponsor, Anna brought several items of interest to our meeting in April 2018—a letter from her friend in North Carolina, a recent newspaper article about the ongoing influence of mothers, and the first issue of Hilltown Life, a glossy magazine focused on “the beauty and vitality” as well as “the challenges and opportunities” of life in the hilltowns of Western Massachusetts (Perkins 4). Having gained so much from literacy sponsors earlier in her life, Anna now takes satisfaction in serving as literacy sponsor for her friends and neighbors.

For Blanche, strong religious faith and the love of music are intertwining themes that run throughout her literacy narrative. In our April 2018 meeting, both Blanche and Anna mentioned that they practice daily Bible devotions. Blanche owns a number of versions of the Bible and likes to compare the nuances of the different translations, to which she is especially sensitive because of her bilingual background. Religious faith and regular Bible reading (or listening on CDs) were important for several of the participants in Suzanne Kesler Rumsey’s study of literacy in older adults. As Rumsey observes, “By ‘practicing’ or engaging their spirits through literate acts, they are able to hold on to what is most important in their lives” (“Holding” 89). Rumsey’s study as well as my own reveal that, for many elders, literacy is a way of supporting and strengthening their spiritual lives.

Throughout her life, Blanche’s involvement with religion and music have often taken place within community, an important source of connection and self-worth since she did not work in a compensated job during most of her adult life. Blanche was active in church organizations, which involved many literacy activities such as planning programs, writing reports, and giving speeches. While living in Long Island, she belonged to her church’s women’s fellowship and taught Sunday school. She was also very active in a national Christian organization, serving as music chairman and prayer chairman for a number of years. After moving to Plainfield full time, she continued this type of involvement, serving as president of Plainfield’s non-denominational Ladies Benevolent Society (LBS) for seven years. Finally she stepped down from this leadership role, explaining that she decided to “let it go to the younger generation. . . . You know, enough is enough.”

Aging well is partially dependent on knowing when to let go, and Blanche had a good sense of when to move on. But moving on doesn’t mean abandoning the sources of literacy that had sustained her in the past. Even now, as a woman in her hundredth year (as she is fond of pointing out), Blanche remains active in community and religious organizations, attending church almost every week as well as monthly meetings of the LBS and weekly sessions of the church-sponsored reading and discussion group. She also regularly joins younger friends who take her to live broadcasts of Metropolitan Opera performances. Blanche’s involvement with music and religion have provided a strong sense of self-worth and identity throughout her life and continue to sustain her in old age.

Rejection of Computer Technology

The one area where all four women felt excluded from literacy was technology—computers and new media. Their refusal to use computers wasn’t just a passive reluctance but rather a clear decision not to engage with this new form of literacy. It was significant that each woman readily identified computers as the most important change in recent years. For example, in 2007, when I asked Kay to talk about important changes she had seen in her lifetime, she answered without hesitation: “Oh, I think the biggest change is this dotcom stuff. . . . And it’s getting bigger [said with emphasis]. I just read something about a young kid who’s twenty-three who’s developed something that’s called Facebook. You know, to me, it has no virtue of any kind. Does it?” I went on to talk about the power of the new technology, and how there are good and bad sides to it. Kay continued, “They said it’s going to change the world. . . . I wonder how it will change the social life of people. How is it going to change their culture?”

Like Kay, Blanche expressed reservations about the new technology:

I feel that I’m out of the mainstream. . . . It’s a little bit frustrating. Not being able to understand. On the other hand, I don’t know that I want to. It would be wonderful to send an email. Somebody will write me a note or a Christmas card and say, “Send me your email so we can correspond.” Well, I don’t have email. So it’s a little frustrating. . . . Things are happening at such a rapid pace that it’s almost impossible to keep things in sequence. We’re bombarded from the radio, we’re bombarded from the TV. All of these terrible tragedies. Things come to your mind that are pretty stressful. And the rapidity of all of this.

She went on to talk about “this new Apple thing”—the iPad.

It’s revealing of the continued active involvement of Kay and Blanche that even though they themselves didn’t use computers, they were aware of recent technology breakthroughs shortly after they came into existence: For Kay, Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook and, for Blanche, the Apple iPad.

Anna, ten years younger than Blanche, is also resistant to computer technology. She explained that she managed to retire from her jobs as postmaster and librarian just as these occupations were becoming more computerized. When we spoke in 2011, she mentioned that her daughter and son-in-law were buying a new computer and wanted to give her their old one, but she had rejected the offer. “I have fat thumbs,” she said. “I can’t deal with all those little keys.”

In her ongoing work on literacy and technology in later life, Lauren Marshall Bowen highlights the tendency in writing studies research to stereotype older people as uncomfortable and inexperienced with digital technologies (“Beyond Repair”; “Resisting”). She has worked to draw attention to elders who are successfully using technology for their own purposes, a trend that will become increasingly important as the century advances. For the women in my study, however, despite their impressive literacies in other areas, the digital world evoked their fears and suspicions, and they chose not to engage with this new type of literacy. In effect, they decided to “alienate themselves from the changes” in literacy tools, one of the options Rumsey describes in “Heritage Literacy” (575-76). These women, so flexible and up to date in other areas, opted not to update their skills with regard to computer technology.

Instead, they developed other ways of coping. For example, Anna devised a low-tech workaround for not being able to enjoy the instant communication of email. As the former town postmaster, she had relied on the US mail as a key link with the outside world all her life. In the cold and snowy winter of 2018, when she was eighty-nine years old, she made it a point to venture out to the mailbox in front of her house each morning with a letter or bill, raise the red flag for mail pickup, and, when the flag was lowered, go back to check for new mail. Clearly not as convenient as sending a quick email, these trips to the mailbox had several advantages. They encouraged her to write something every day, enabled her to communicate regularly with older friends who didn’t use computers, and provided daily doses of fresh air and exercise.

Blanche’s solution was to make the most of the telephone—a breakthrough technology in her youth. Having given up driving in her early nineties, Blanche relied on the phone to maintain close contact with her friends and relatives. Speaking personally, I can confirm that receiving a phone call or voice mail from Blanche is like having a face-to-face visit. The warmth and caring in her voice come right through the phone line in a way that no text or email can ever equal.

Although none of the women in my study are computer literate, this has been a conscious choice on their part. They prefer to rely on the communication technologies that served them well in the past.

Differing Views of Themselves as Readers and Writers

Although most of the literacy experiences the women recalled as meaningful occurred outside of school, the educational opportunities available to them as young women have shaped their uses of literacy in later life. All four women were intellectually inclined and would clearly have benefitted from a college education. But primarily because of family economic circumstances aggravated by the Depression of the 1930s, only two, Irene and Kay, were able to achieve that goal. Both of Irene’s parents were college graduates, and they were determined that their children would get a college education. Kay’s family was the most prosperous of the four. Her college-educated father was working in a management position with an income that enabled him to send both daughters to college despite the hard economic times. Blanche and Anna were not so fortunate. As a child of immigrants, Blanche took the commercial course in high school and had to find a job after graduating. Anna’s parents were making ends meet with their small farm, but college for their children was a luxury beyond their means.

This educational history may help to explain the different ways the women have used writing in their later lives. Anna and Blanche saw writing as a useful skill for accomplishing certain tasks of daily life, but they did not regard themselves as “writers.” In contrast, Kay and Irene, the two college-educated women, went beyond these everyday uses of writing in an effort to explore ideas and communicate in the wider world outside their immediate social circle.

The women’s different uses of writing reflect a trend in twentieth-century literacy. In “Remembering Writing, Remembering Reading,” published in 1994, Brandt makes the point that for most of her interviewees' reading seemed to have a higher and more universal status than writing as they looked back on their earlier lives:

On the whole it must be said that the status of writing in everyday literacy practices is decidedly more ambiguous and conflicted in comparison to reading. . . . [W]riting seems to be experienced more as an embedded means than a demarcated end in itself. Writing does not seem to be as broadly sponsored and endorsed by parents; nor does the identity “writer” seem as unproblematically available as the identity “reader.” (470)6

This generalization held true for Blanche and Anna. While they were eager to talk about themselves as readers, they did not regard themselves as writers in a creative or aesthetic sense. It’s important to point out, however, that reading, like writing, is a form of meaning-making and, as such, can be of great value for older adults. In her landmark book, The Reader, The Text, The Poem: The Transactional Theory of the Literary Work, Louise M. Rosenblatt called attention to the ways in which readers actively create what she called “the poem” as they read poetry, a novel, or even a piece of informative nonfiction. Readers construct the meaning of what they read, and these meanings differ at different times of life. Thus, an active reading life remains a significant way of making meaning in the elder years as it was for the women in this study, one of the keys to their continued involvement and vitality.

When I asked about the role of writing, Blanche and Anna initially thought I was talking about penmanship, a skill that was stressed in their early educations. Both did go on to talk about letter writing as an important life skill. For example, in the past few years Anna has been exchanging long, informative, and carefully composed letters with a dear friend and neighbor who moved out of town to live near one of her children. These letters not only serve as a way of staying in touch but also provide a means for Anna to think reflectively on subjects of her own choosing. She often encloses a clipping she thinks would be of interest to her friend with a note written in the margin, “What do you think of this?”

Letters also play an important role in Blanche’s life. She mentioned listening to a radio program focused on “the lost art of writing letters.” Speaking with great emotion, she said, “It’s so sad because once the emails are erased the record is gone. You have no record of these beautiful letters like Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote back and forth, these beautiful things that are on paper.” Like the famous poets, Blanche and her fiancé (who later became her husband) exchanged letters: “I still have his old letters upstairs.” They are among her most treasured possessions.

Like many of the people Brandt interviewed (“Remembering”; Literacy), Anna and Blanche were fully literate and used writing as needed in their daily lives. But they did not view themselves as writers. Irene and Kay, on the other hand, used writing not only for instrumental purposes but also for aesthetic reasons and as a way of asserting their agency in the world.

Writing for a Wider Audience: Irene and Kay

Throughout their adult lives, Irene and Kay had used writing as a way of reaching out to a world beyond the local community. As they grew older, writing became even more important as a way of formulating and expressing their views. At a time of life when activities such as participating in a political demonstration or attending a lecture had become difficult, writing provided a way to stay actively involved in the wider world.

A theme that runs throughout Irene’s literacy experiences from the school years through old age is writing as a public act. Chosen as class poet at age sixteen, Irene continued to have a way with words throughout her life. In fact, her facility with writing helped to pay for her college education. As Brandt points out, in the twentieth century media sources such as magazines or television programs promoted literacy by sponsoring contests (“Sponsors” 166-67). It was through one such competition, an essay contest sponsored by the Birmingham News, that Irene won a full scholarship for the first and last years of college.7 During her career as an opera singer, Irene continued to use her writing in the public sphere, writing program notes and professional bios for her singing engagements. Much later in her life, Irene engaged in another form of public writing, composing letters to elected officials. As she told me in an interview, about a year after the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, she wrote a letter of concern to then President George W. Bush, criticizing his war policies. She had hoped to receive a reply from the President but instead got only form letters requesting donations. After Irene’s death in May 2016, her sons found a copy of this letter among her papers and decided to read it at her memorial service. To them, it exemplified an important character trait: their mother’s belief that, as a citizen in a democracy, she had a right and a responsibility to express her opinion to the highest public official. And she saw writing as a way of doing this.

For Kay, a fascination with history, which was sparked during her season in Paris as a young woman, provided a theme for writing in later life. When she and her husband retired in 1977, she devised a project that would combine three of her lifelong interests: writing, visual design, and history. After a three-week road trip tracing the travels of her paternal grandfather, who had been a bugler in the Civil War, she produced a book that included copies of his writings (his diary and sixteen letters) along with her narrative of his travels during the war. Kay had the complete document photocopied and bound—an important piece of family (and national) history.

Another type of writing that is often especially meaningful in old age is the life review. In 1999, when a “writing group for seniors” was offered in neighboring Cummington, Massachusetts, both Irene and Kay decided to participate. In Beyond Nostalgia: Aging and Life-Story Writing, Ruth Ray, a gerontologist and writing studies scholar, theorizes the value of this kind of writing in later life, drawing upon her own experiences as a participant-observer in eight different senior writing groups over a three-year period. In the book’s introduction, she explains her rationale for taking a narrative approach to this subject:

From my position as a feminist, life stories are rich examples of gender negotiations; they are language acts that make visible the different ways men and women “write the self” in old age. They also illustrate the different paths of development available to men and women across the life course. (27)

Looking back on one’s life, using words to make meaning of the past, is an important task at any time of life, but is especially significant in old age (see also Jerome Bruner, 110-36, for a discussion of the construction of the self in autobiography).

But if people do not see themselves as writers, as seemed to be the case for Blanche and Anna, they may feel intimidated by the thought of joining a writing group. Even Kay, never one to shy away from new or challenging situations, had some hesitation before eventually signing up. She expressed these reservations in a handwritten metacognitive reflection, which she later attached to her copy of the group’s photocopied publication:

Somehow, somewhere it was suggested to me, there would be a creative writing course to attend in Cummington. I felt that I am not a candidate for writing and thus dismissed the idea. However, the word creative kept recurring in the recesses of my mind. When the offer to take advantage of this Tuesday morning event was again mentioned, I thought, “Why not?” It’s been a general habit of mine to venture into new or different experiences.

According to Ray (22-26), the communal aspect of writing workshops for elders is of key importance as the “self” is constructed in dialogue with others (either real or imagined). The facilitator of the Cummington group, Wynne Busby, emphasized this in introducing the group’s publication: “I am grateful for the richness of the stories we have told each other, . . . and for the warmth of our little community during these ten weeks. There was commonality, laughter, a few tears as someone touched a nerve now and then” (n.p.). Kay and Irene each had three pieces in the group’s publication.8 In these personal reflections, the women explored memories of their childhood and analyzed turning points in their lives as adults. Like many other elders, Kay and Irene benefited from this opportunity to reflect on people and experiences from the past, using words to make meaning in old age within a supportive community.

Perhaps the confidence Kay gained through sharing her writing with others in this workshop was a factor in her decision, at age ninety, to begin a series of reflective writings in which she worked to express what aging had meant in her life. This decision was typical for Kay, who throughout her long life felt the need to work things out for herself and not just rely on accepted wisdom. In one of our interviews, Kay explained:

I don’t know why, but I had the feeling that . . . for some reason I wasn’t born to know all of this stuff the other kids seemed to know. And then I thought, “Oh, well. So what? I’ll make it out on my own.” And I think that idea has stuck with me the rest of my whole life, that I’m responsible.

Many years later, Kay applied this same attitude to understanding the meaning of aging. Written over a period of nearly ten years and shared with many friends in the community, these writings constitute a valuable archive of aging—reflections on what it means to grow old from someone in the midst of the process. In this way, Kay was working actively to make meaning in—and of—old age.

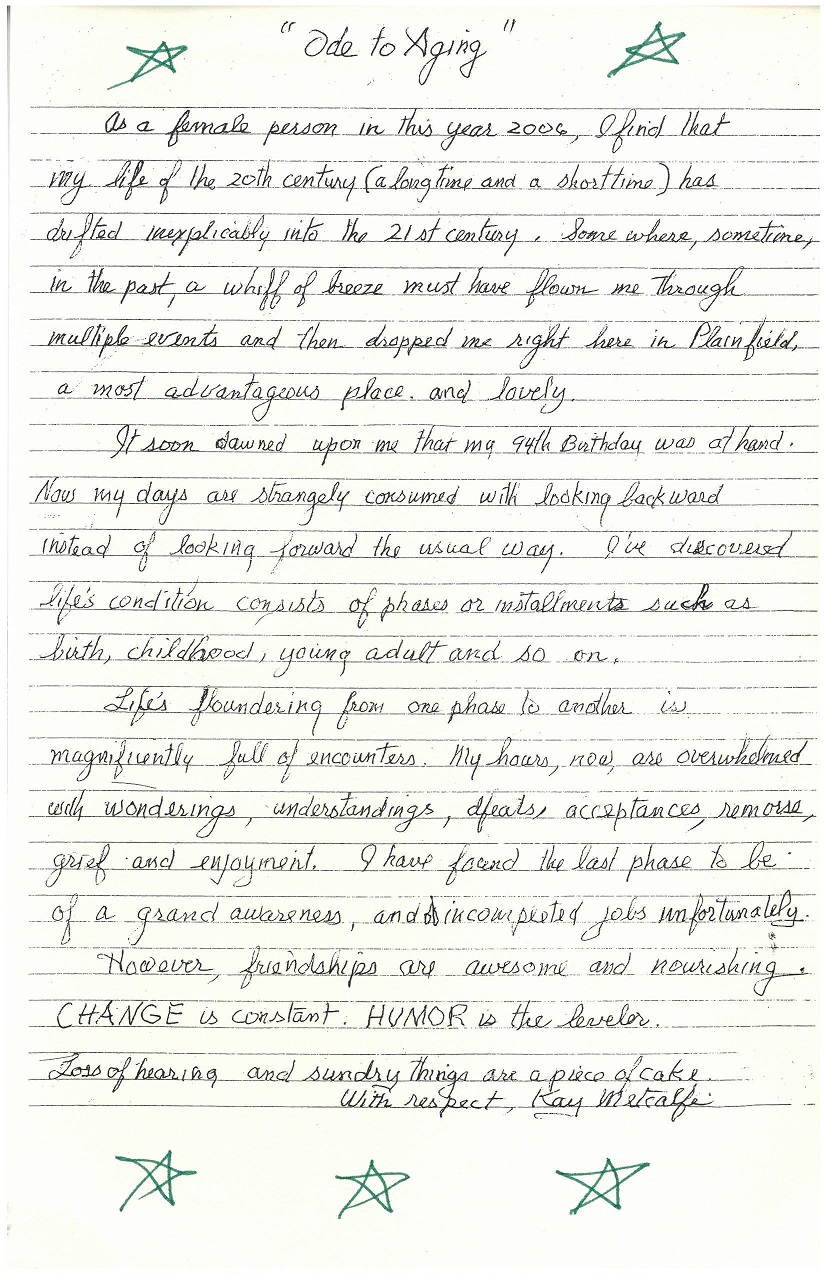

In the first of these pieces, Kay uses a metaphor she would invoke many times as she describes ending up “somehow on the other side of the ‘Looking Glass’ where I had never been before. From there, there would be no return.” In “Ode to Aging,” written in 2006, when she was ninety-three, she expresses the sense of “drifting” or “floundering” into a new time of life (see Figure 2). She finds this “last phase” to be one of “a grand awareness.” The next year, still grappling with her own mortality, she writes: “How I wish the knowledge in one’s brain, especially of great importance would survive after death. How can it pass into oblivion?” These reflections, written at the end of her life, were one way Kay hoped to pass along the knowledge she had gained. The deepest, most philosophical of these writings is a poem entitled “Motion Is not Stationary,” composed in 2007 and influenced by her reading of Walter Isaacson’s biography of Einstein. In this poem she shares understandings that had evolved over the course of her life.

Fig. 2: Kay’s “Ode to Aging”

The last of Kay’s writings on aging, composed in 2011, when she was ninety-eight, reflects her basic optimism tempered by the realization that “Old Age is busy now, showing off its inordinate skills.” This reflection was originally written as a prose piece, but a friend, herself a poet, encouraged Kay to reformat it as a poem and publish it in the local newspaper, the Plainfield Post.9

While others in her age group may feel silenced by society’s negative view of old people, Kay Metcalfe, as she became one of the “oldest old,” decided to share her perspective on aging with others in this series of writings. At a time when she was struggling with hearing loss, which greatly interfered with oral communication, Kay used writing to transmit to others the essence of what she had learned from living. This was a task she took extremely seriously, revising many times as she struggled to express her thoughts on this most profound of subjects. As Kay grappled with old age, her literacy, honed since childhood, enabled her to broaden what she could accomplish at a time of life when many others retreat into silence.

As the proportion of elders in the world population grows dramatically,10 it is important to recognize the role that literacy can play in aging well (Beal). The type of reflective writing that Kay did during her nineties has great potential as a way of coping with the challenges of aging. Composing a narrative is a way of organizing complex, often disturbing, occurrences into a coherent whole, a way of bringing structure and meaning to life experiences (Pennebaker and Seagal, 1250). Experimental studies conducted over many years and with many different subject populations have found a direct correlation between writing about (and analyzing) traumatic events and improved physical and psychological health (see, for example, Pennebaker, Opening Up, “Writing About,” Writing to Heal; Pennebaker and Seagal).

For Kay, using writing to reflect on what it means to grow old was a way of doing the kind of mental processing that geriatric psychiatrist Gene Cohen feels is an important task in the years after seventy. At this time of life, people “feel more urgently the desire to find larger meaning in the story of their lives through a process of review, summarizing, and giving back. . . . [W]e begin to experience ourselves as ‘keepers of the culture’ and often want to contribute to others more of whatever wisdom and wealth we may have accumulated” (75-76).

Partly as a result of her writings about aging, Kay was seen by many in Plainfield as a positive role model. In 2012 she received the “Gold-Headed Cane,” awarded to the town’s oldest resident. After her death in 2018, the selectmen (the town’s governing board) decided to dedicate the town’s annual report to her memory. They asked me to write the dedication, and I used this opportunity to quote from her reflective writings on aging.

Making Meaning Across the Lifespan

In her book Ageing, Insight and Wisdom: Meaning and Practice across the Lifecourse, Ricca Edmondson stresses the importance of meaning making within the context of a person’s entire life: “To neglect this aspect of lives, bitterly misrepresents them: making meaning is a socially and existentially significant activity” (15). She emphasizes the need for society to focus more on the ways that people make meaning in old age and less on how they are (or are not) contributing to the economy (197-205). Recognizing the strengths and resources of our elders counteracts the common tendency within gerontology and society at large to focus on the frailties and illnesses of old age. Considering how older people use reading and writing to construct meaning is one important way of focusing on growth and development rather than decline.

Now, more than ten years after beginning my study, I have learned a great deal about the role of literacy in aging well by looking closely at the lives and experiences of four remarkable women. As I reflect on what I have learned, I think about Irene writing a letter critiquing the foreign policy of President George W. Bush. I think about Anna walking out to her mailbox, hoping for a letter from her friend. I think about Blanche, who, at age ninety-nine, still reads from the Bible every day and regularly attends a church-sponsored reading and discussion group. And I think about Kay, who, over a ten-year period, used her own reflective writing to explore what it means to enter the land of the oldest old. For these women, reading and writing are part of a continuing narrative, providing a way of relating to the world and making meaning at a time of life when other activities may no longer be possible.

As I conclude this discussion of literacy across the lifespan, I keep remembering something Irene said in our 2007 interview:

I love words. I think words are fascinating. . . . You know, I love that chapter in the book of John: “In the beginning was the word. And the word was with God. And the word was God.” You know, it says He spoke the worlds into being. He said, “Let there be light. And there was light.” Words have a power beyond almost anything that we know of.

With her belief in the power of words, Irene could have been speaking for all four of the women. A lifelong fascination with words has been an important factor in their ability to age with grace and resourcefulness. For these women, active engagement with reading and writing has taken on a particular power in the elder years as they use words to make meaning of their lives.

I wish to express my deepest gratitude to the four women who participated in this study. I offer heartfelt thanks as well to Lauren Marshall Bowen and Suzanne Kesler Rumsey, editors of this special issue of Literacy in Composition Studies, for their thoughtful and detailed responses to earlier drafts of this article.