Abstract

Caregiving is a critical and yet understudied area related to aging, health, and wellness. Despite the importance of caregiving in the lives of older adults, assumptions about aging “actively” or “successfully” suggest that aging is independent, not interdependent. The healthcare industry reiterates these gerontological assumptions about aging when invoking notions of skills-based health literacy. This essay is an analysis of and response to the rhetorics of literacy as used in health care. Using John Duffy’s theoretical framework for literacy development as well as scholarship in age studies and community-literacy studies, I argue that literacy has become a rhetorical construct that promotes a view of older adults as particularly draining on the healthcare system. A more productive approach would be to frame the collaborative, distributed, and mediated work of giving and receiving care in the context of Paul Prior’s concept of literate activity. Finally, with a community-literacy approach that incorporates engagement and dialogue rather than individualistic skill development, I respond to this rhetorical construct of health literacy by considering how aging, interdependence, and networked caregiving expand the notion of what contributes to healthy living and well-being as we age. Using examples from a community care coordination project, this essay shows how compositionists might work together with patients, caregivers, and professionals to reframe health literacy rhetorics and act for change.

Keywords: health literacy; literate practice; caregiver; older adults; interdependence; care networks

Contents

Framework and Method: Rhetorical Conception of Literacy

The Rhetorics of Health Literacy in the Health Literate Care Model

From Skills-Based Health Literacy to Distributed Literate Activity

A Community Literacy Studies Model for Networked Caregiving

Toward Networked Caregiving as Literate Activity

Conclusion: Toward a New Rhetoric of Literate Care

Introduction

Over the past two years, as I have collaborated on a clinical study of communication between clinicians and human services professionals who support the health and wellness of older adults in mid-Michigan, I have spent a good deal of time before meetings waiting in clinic and office reception areas, casually chatting with older adult patients/clients and their caregivers (or others who receive care by the patients/clients themselves). I have met many informal caregivers such as parents, children, grandchildren, and life partners, as well as formal (paid) caregivers, such as home health aides (HHAs), personal care assistants (PCAs), certified nursing assistants (CNAs), and transportation assistance providers. In all of my time in these waiting rooms, it is rare to meet someone who is alone.

Caregiving is a critical and yet understudied area related to aging, health, and wellness. In 2000, the U.S. Census documented 2.4 million grandparents raising 4.5 million grandchildren under age eighteen, a 30% increase from 1990 (Simmons and Dye). In 2015, about 34.2 million Americans provided unpaid care to an adult age fifty or older in the last twelve months, and of these, 66% report that they have significant decision-making authority regarding the care recipient’s condition and adjusting care. Fifty percent of family caregivers act as an advocate for the care recipient with care providers, community services, or government agencies (National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP). Age studies scholar Svein Olav Daatland argues that more intergenerational studies of aging involving caregiving are crucial to an understanding of norms and ideals about aging and their societal implications (124).

Yet, despite the importance of caregiving in the lives of older adults (either as a caregiver or receiving care), assumptions about aging “actively” or “successfully” suggest that aging is independent, not interdependent. As Suzanne Kesler Rumsey discusses, a version of the controversial “successful aging” paradigm is focused on activities or tasks performed by an older adult that can be objectively measured (86-87, citing Boudiny). Further, popular television and print media targeted at older adults, such as AARP Magazine, circulates problematic discourses of older adults in a “curriculum of aging” that promotes self-management of bodily decline (Bowen). These narratives lie in sharp contrast to work in humanistic approaches to aging, which emphasize interdependence, solidarity, and increase in life satisfaction across the lifespan (Glass and Vander Plaats).

The healthcare industry reiterates problematic assumptions about aging when invoking notions of skills-based health literacy. The skyrocketing costs of health care, connected to the exponential increase of older adults managing chronic conditions as a proportion of American healthcare consumers, has created a health care “crisis” in America, an ageist crisis that, as age studies scholar Stephen Katz writes, “project[s] [older adults] as a monstrous entity set upon destroying welfare states and generational futures” (18). The healthcare industry articulates remedies to this financial crisis through discourses of health literacy and patient engagement, particularly focusing on preventative care and self-management of chronic conditions. In order for a perceived aging American population to self-manage their chronic conditions and be more engaged in their own health care, the medical community urges more health literacy education. For example, in a study of 3,260 older adults with Medicare-managed healthcare plans, the participants took the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy and then were assessed in terms of their medical costs. The study found that those participants with low health literacy incur more medical costs and “use an inefficient mix of services” (Howard et al. 371). However, health literacy, narrowly defined as “the ability to understand and act on health information” (McCray 152), is a problematic lens—much like “successful aging”—for viewing aging and care in the twenty-first century, as it locates the problem with the individual, alone.

This essay is an analysis of and response to the rhetorics of literacy as used in health care. Using John Duffy’s theoretical framework for literacy development as well as scholarship in age studies and community literacy studies, this essay analyzes the rhetorics of literacy as used in health care; namely, how literacy becomes, as Wysocki and Johnson-Eilola argue, a “metaphor for everything else” (349). With a community literacy approach that incorporates public engagement and distributed literate activity rather than individualistic skill development, I then respond to this critique by considering how aging, interdependence, and networked caregiving expand the notion of what contributes to healthy living and well-being as we age. This supports a humanistic age studies approach rather than a deficit model of aging.

To illustrate this, I use examples from an action research project that creates online spaces for networks of professionals and caregivers to work across health care and community. Implementing a tool that enables communication across spheres of writing, this work illuminates the networked, distributed, and collaborative nature of composing a healthy life in the twenty-first century, as caregivers and patients—across the lifespan—work together with their healthcare professionals. The implications of this project are many for literacy, composition, and age studies scholars across fields of study and sites of practice, including a more expansive view of how we all might contribute to building dialogue and understanding across difference (Flower) in clinical, community, and home health settings. This work opens up space for us all to live interconnected to one another and more focused on improving the fabric of our communities.

Framework and Method: Rhetorical Conception of Literacy

In Writing from These Roots: Literacy in a Hmong-American Community, John M. Duffy presents a framework that he calls a “rhetorical conception of literacy” (17). Drawing from Kenneth Burke’s “wider context of motives,” Duffy argues that

all elements of literacy instruction, including the selection of reading materials, the choice of teaching methodologies, the assignment of essay topics, and even the teacher’s conception of the learner are ultimately rhetorical and ideological, ultimately intended to promote a vision of the world and the place of learners within it. (17)

Duffy continues to say that “the terms ‘rhetoric’ and ‘rhetorics of literacy’ are meant to indicate these opposing possibilities—the ways in which reading and writing can be used to define, control, and circumscribe, but also the ways in which human beings can use written language to turn aside, re-create, and re-imagine” (18).

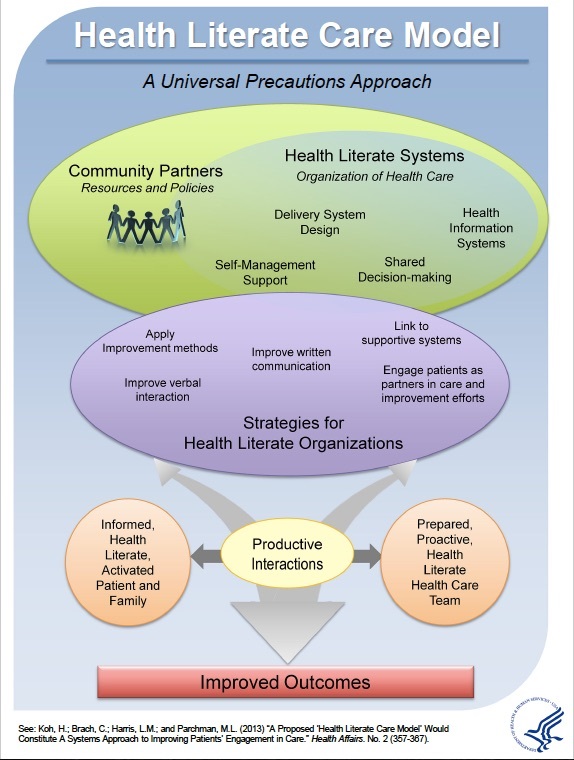

To critique the rhetorics of health literacy, I use Duffy’s framework to analyze the Health Literate Care Model, an approach to healthcare practice endorsed by the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) for adoption by healthcare organizations as a model to engage patients in prevention, self-management, and decision-making (Fig. 1). The Health Literate Care Model presents a set of strategies that reinforces the notion of health literacy as an independent and self-sufficient act, leaving little room for caregiving and socially constructed notions of health and wellness proposed by humanistic age studies research. From this analysis, I argue that the Health Literate Care Model presents an opportunity to reframe discourses of aging and health and wellness inside and outside of the healthcare system. The curriculum of aging that the model reinforces emphasizes independent, autonomous patients working alone on their own health, absolving the healthcare industry of any unequal power differentials that the closed system of health care may sustain.

Fig. 1. “Health Literate Care Model: A Universal Precautions Approach.” Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Interactive graphic available athttps://health.gov/communication/interactiveHLCM/

To address this, I re-imagine and theorize one component of the Health Literate Care Model—community care coordination—that coordinates both health and social support services within a community (AHRQ). Community care coordination expands the focus of health and wellness beyond the clinical setting and into the communities in which patients live and work. To coordinate care across contexts, healthcare and social services professionals, caregivers, and others need spaces to write and interact. Using examples from a community-engaged, action research project (a community care collaboration project with team members including myself and professionals from a senior health clinic, a legal services clinic for older adults, and social services organizations), I then present strategies for networked writing to support interdependence and the building of interconnected care throughout the lifespan.

The Rhetorics of Health Literacy in the Health Literate Care Model

In 2013, the Assistant Secretary for Health and Human Services, Howard Koh, and a research team proposed a new healthcare delivery model for healthcare providers in the US called the Health Literate Care Model (Fig. 1; Koh et al. 357). This model grew out of the Chronic Care Model, widely adopted in the 2000s, and weaves into that older model health literacy strategies for “patients’ full engagement in prevention, decision-making, and self-management activities” (Koh et al. 357). Coinciding with the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), this new model supports certain incentives under that legislation, such as the creation of patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations. These are team-based approaches to care that integrate medical practice across a team of providers and other sources of support for the patient (see Fig. 1).

While a team-based approach to care is laudable and a step forward from clinic-focused medical models, the model’s adoption of the term “health literate” continues to pose ambiguity. The model refers to “health literate” systems, organizations, and teams, as well as patients and family (see Fig. 1). What does it mean for all of these entities to be health literate? The Health Literate Care Model’s co-authors describe it this way:

As noted in the Affordable Care Act . . . engaging patients in their own health care fundamentally relies on health literacy—that is, their ability to obtain, process, communicate, and understand basic health information and services. Unfortunately, relatively few people are proficient in understanding and acting on available health information to fully engage in their own care. . . . We then propose a new Health Literate Care Model based on “health literacy universal precautions”—that is, the need for health care providers to approach all patients with the assumption that they are at risk of not understanding information relevant to maintaining and improving their health. (Koh et al. 357-58)

Koh et al.’s description of health literacy is technically narrow (a set of skills) and yet expansively broad (skills across reading, writing, speaking, listening, cognition, decision-making, etc.). Anne Wysocki and Johndan Johnson-Eilola describe this seemingly contradictory phenomenon of defining literacy in their essay, “Blinded by the Letter: Why Are We Using Literacy as a Metaphor for Everything Else?”, in which they write, “Too much is hidden by ‘literacy,’ we think, too much packed into those letters—too much that we are wrong to bring with us, implicitly or no” (349). They elaborate in arguing that “[w]hen we speak of ‘technological literacy,’ then, or of ‘computer literacy’ or of ‘[fill-in-the-blank] literacy,’ we probably mean that we wish to give others some basic, neutral, context-less set of skills whose acquisition will bring the bearer economic and social goods and privileges” (352). Koh et al. posit that a set of enumerated skills bring health and wellness. Yet, Koh et al. are invoking a system that implicates many more stakeholders beyond the patient. In fact, in the Health Literate Care Model, as much or more of the burden lies on changing providers’ skills. Health literacy, then, is the wrong term to use.

A more accurate term for the work the Health Literate Care Model seeks to do can be found upon returning to Duffy’s rhetorical construction of literacy. He asks us to consider, “how is literacy implicated in our constructions of identity, perceptions of reality, and exertions of power over one another?” (5). It is important to remember that health care in the United States today is a three-trillion-dollar, for-profit industry, and that the “crisis” of the economic model—that older adults purportedly put more stress upon—does not have to be in crisis, and certainly is not in other countries (Rosenthal 244). This crisis is a construction framed in the public discourse of health care as an economic problem (Segal 119), and also framed as the increasingly aging and expensive U.S. population destroying health care. As Elisabeth Rosenthal, editor of Kaiser Health News, argues,

Every other developed country in the world delivers healthcare for a fraction of what it costs here. They use a wide range of tools and strategies that line up with each country’s values, political realities, and medical traditions. Some set rates for healthcare encounters. Some negotiate prices for drugs and devices on a national level. Some have the government administer payments. Some mandate transparency. (243-44)

Rosenthal’s argument re-emphasizes how America has chosen to frame our healthcare debate in terms of financial crisis as a strategy for control of that debate. Unfortunately, one result of this framing is that aging (and the correlated management of increased chronic illness) is painted as contributing to that crisis to the detriment of younger Americans.

The low health literacy of older adults is implicated as a convenient explanation of this crisis. However, the invocation of poor health literacy of individuals is also designed to mask the increasingly bureaucratic imbroglio of American health care. There are very few people that do not have difficulty navigating the American healthcare system, so much so that an Institute of Medicine discussion paper redefined health literacy to be both related to an individual’s competencies and to the complexity of the system (Brach et al.). As Ruth Parker argues, the “roots of health literacy problems have grown as health practitioners and health care system providers expect patients to assume more responsibility for self-care at a time when the health system is increasingly fragmented, complex, specialized and technologically sophisticated” (278). Rather than expanding an already problematic notion of literacy, I assert that the fragmentation and brokenness of the American medical-industrial complex should be the focus of the national health care discussion, and the use of the term literacy turns us away from doing precisely this. The deficit to be attended to is the system’s, not the individual patient’s.

Literacy is currently used by healthcare researchers and professionals as a term for privilege, or lack thereof, across economic, political, social, and technological barriers to access to care. This is where health literacy meets health equity, which is defined as “the absence of systematic disparities in health (or in the major social determinants of health) between groups with different levels of underlying social advantage/disadvantage—that is, wealth, power, or prestige” (Braveman and Gruskin 254). The lenses of health equity and the social determinants of health help us to move beyond a biomedical focus on health literacy, or one that focuses on a patient’s competency or deficiency in skillset or abilities. Instead, the focus is on improving health and wellness outcomes through addressing what may in fact be the primary roadblocks for many to become or stay healthy—lack of healthy food, transportation, housing, education, and other cultural and social (nonmedical) factors. The social determinants of health are largely socially situated and not individually determined, and much like those in New Literacy Studies, scholars who research health equity ask questions related to the “larger structural, systemic, and global forces that shape local contexts” (Duffy 10). These are questions of equity that the invocation of literacy obscures.

These lenses of health and equity and the social determinants of health also help us move beyond ageist notions of linearly-declining health and health literacy, and towards a postmodern, reflexive, and critical vantage point, aligning conversations in health with those in critical gerontology and age studies (Katz 19). Health inequities can exist at any age and are often intersectional in scope. Biological factors alone do not determine what may be needed from health care. Indeed, caregiving may be necessary at multiple times and places throughout the lifespan. This is why caregivers are of every age, as are those cared for. A positive psychological view, for example, challenges the notion of decline as we grow older, and points to older adults as caregivers as nurturing of empowerment, strength, and growth (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi). What is important is to achieve a cultural acceptance of caregiving and support for caregiving throughout our lives.

The word literacy obfuscates the social determinants of health and the social justice-oriented, activist work that is inherent to improved health and wellness for groups historically disadvantaged by systems such as the medical-industrial complex. As Wysocki and Johnson-Eilola write, “the word [literacy] keeps us hoping—in the face of lives and arguments to the contrary—that there could be an easy cure for economic and social and political pain, that only a lack of literacy keeps people poor or oppressed” (355). They end on a note that brings us back to caregiving: instead of skill development of individuals, we should look at how we build spaces and how we all might best participate in these spaces together (Wysocki and Johnson-Eilola 366). How might we all work together—across the lifespan—to promote a culture of care as we age?

In order to work together, the discussion of health literacy must change to reflect the roles that all stakeholders play in the construction of a culture of care, particularly given the importance of caregivers across the lifespan. An older adult may have a caregiver, may be a caregiver for an aging spouse, or may perform caregiver duties for grandchildren or other family members in the home. A greater understanding of interdependence of older adult patient and caregiver, as well as the broader caregiver experience, is necessary to build this culture of care. For example, in Shelby Garner and Mary Ann Faucher’s study of family caregivers of older adults, they find that consistent themes emerged related to caregiver challenges, including scheduling of appointments, medication adherence, being perceived as interfering, and having to constantly problem solve (68-69). One participant in their study noted, “Combat. I have to gear up my weapons, lie low, and approach the obstacles I face and fight” (69). Garner and Faucher argue that “identifying and understanding the perceived challenges and supports experienced by caregivers is imperative for development of policy, programs of care, and crafting communication between the health care provider and the family caregiver” (63). Garner and Faucher’s study highlights the dissonance between what I witness in the waiting room—the families and networks of support surrounding the older adult patient—and the perception of a solo older adult patient navigating the health care system alone, or alone in concert with their physician. Health care as we age involves a revolving door of actors, from family members to specialists to community resource providers, and we need a framework for literate health practices that includes these actors.

Paul Prior’s concept of writing as literate activity provides an important foundation. To Prior, writing is “situated, mediated, and dispersed. . . . Literate activity, in this sense, is not located in acts of reading and writing, but as cultural forms of life saturated with textuality, that is strongly motivated and mediated by texts. Given this perspective, it becomes particularly important to examine the concrete nature of cultural spheres of literate activity” (138). In the context of older adult patients, Prior’s definition illuminates three sets of dichotomies (see Table 1) and the importance of resolving each of them by replacing the left-hand column with the right-hand column, or a more expansive, adaptive socio-cultural approach to literate activity in the health care context. The first dichotomy is between a skills-based literacy approach and a literate activity approach to health (similar to all patients yet disproportionately experienced by older adult patients due to their perceived drain on the health care system). The second dichotomy exists between a biomedical model of aging and a positivist view that incorporates the cultural and social worlds of older adults. The biomedical model focuses on what might be measured in the clinical setting, while a positivist view of aging reflects the social and cultural dimensions of the older adult patient, including home and community contexts. Finally, it is not surprising that the first two left-hand column positions in Table 1 (individual patient and biomedical model) would align with models of healthcare economics, in that what is specifically measurable in the clinical setting is also quantifiable in the health care system. Literate health activity would instead frame a health care model that takes into account care inside and outside of that system, and focus on value to patient rather than cost of clinical care. Health literacy is a convenient rhetorical framing to sustain the biomedical, for-profit model of health care. For this reason, it is critical to bring literacy studies scholarship to the context of health literacy.

Table 1. Differing Approaches to Health Literacy for Older Adults: Health Literacy Versus Literate Health Activity.

Health literacy |

Literate health activity |

Focus on individual patient |

Focus on collective and distributed action |

Focus on biomedical models of aging |

Focus on culture and social worlds of older adults, includes home and community |

Cost-based; focus on for-profit model of medical-industrial complex |

Care-based, focus on value to patient |

A literate health activity approach also makes space for a humanistic approach to aging and acceptance of interdependence in the care of older adult patients. The participant-caregiver in the Garner and Faucher study referred to her involvement with health care “combat” (69) in part because there is no belief in or space for her involvement in her parent’s health decision-making. The assumed relationship is expert doctor/compliant patient, so the advocate caregiver must be rocking the boat. This is in direct opposition to aging studies research that indicates that older adult patients who choose caregiver assistance have more comprehensive medical visits and feel more supported (Prohaska and Glasser). With an acceptance of distributed health literate activity (in conjunction with greater appreciation for shared decision-making practices more broadly), a more robust understanding of the distribution of labor across collective actors would replace a battle with a collaboration.

A Community Literacy Studies Model for Networked Caregiving

A humanistic approach to aging and interdependence in the healthcare setting requires a cultural shift that requires dialogue across differing epistemological positions. Community literacy studies offers a framework to intervene in the discourse of health literacy and to present an explicit move away from the biomedical model of both literacy and aging as individual skills/abilities or a lack thereof and toward a collective, distributed set of mediated actions to give and receive care. The Health Literate Care Model recommends “health-literate” community partnerships across clinical and community contexts. This is often called community care coordination, or working in a team with medical and non-medical professionals and caregivers to coordinate care. This recommendation is an extra step above what was previously recommended under the Care Model, which was to encourage individual patients to take these steps alone.

In the context of older adult patients, this is invisible labor that would often be performed by the same caregivers that I meet in the waiting rooms of clinics. These caregivers often are given a handful of brochures for free services as they leave with their relative or client, and it is up to them to attempt to apply and receive the services on their own time, rather than have an integrated approach whereby the clinic could streamline application and referral processes, and better support caregivers. A more networked and collaborative approach to care is a significant cultural shift for clinical practice, and for this reason, the ACA contains incentives to attempt this relationship building and practice transformation. This is a new and controversial activity, as it takes time separate and apart from the fee-for-service care that healthcare clinics and hospitals typically provide. For example, if a provider spends an hour on the phone with Meals on Wheels to ensure that a patient is eligible for services, that is not an hour that can be billed in the same way that a patient visit can be billed. Further, information technologies such as the electronic medical record do not facilitate data sharing outside of a siloed healthcare system. This is why the ACA (and some health insurance plans) incentivize this work—because under the current system, the healthcare provider loses time and money to try to work with caregivers rather than delegate work to them.

These incentives create an opportunity for a networked, caregiving-focused community literacy project. Healthcare providers, patients and caregivers, and human services professionals have very different vantage points when it comes to health care delivery, but all would agree that health care delivery is a site of struggle (or “combat,” to continue the metaphor) in the United States today. From waiting room to nursing station to ivory tower, all agree that coordinating care inside and outside of the clinic is close to impossible. What all stakeholders are looking for—across institutions and communities—is a space in which to communicate with one another. That is, where can providers, caregivers, and community-based professionals work together? Linda Flower’s rhetorical model of community literacy allows us to envision strategies for literate action (discovery and change) that simply cannot be envisioned within the rhetorics of health literacy. Flower describes community literacy as:

an intercultural dialogue with others on issues that they identify as sites of struggle. Community literacy happens at a busy intersection of multiple literacies and diverse discourses. It begins its work when community folks, urban teens, community supporters, college-student mentors, and university faculty start naming and solving problems together. It does its work by widening the circle and constructing an even more public dialogue across differences of culture, class, discourse, race, gender, and power shaped by the explicit goals of discovery and change. In short, in this rhetorical model, community literacy is a site for personal and public inquiry and, as Higgins, Long, and Flower (2006) argue, a site for rhetorical theory building as well. (19)

A community literacy rhetorical model offers an opportunity for older adults to advocate for resources necessary for healthy aging. For example, caregivers, as well as older patients like the older adult participants in interviews conducted by Philippa Spoel, Roma Harris, and Flis Henwood, have the ability to push back against deficit notions of aging and advocate for services that may be necessary to comply with healthy living recommendations (141). A health care professional may not be aware that the infrastructure simply does not exist for a particular patient to be well; for instance, she may prescribe more exercise to control a condition such as obesity, yet without hearing about constraints from a patient or caregiver, may make the recommendation and blame a negative outcome on a patient’s deficient health literacy. A care coordination plan instead requires that inquiry across difference take place so that caregiving is distributed across home, community, and clinic, and so that caregivers are visible in the equation of care.

In sum, the Health Literate Care Model is problematic in its adoption of the rhetorics of health literacy but is still an opportunity to begin considering what a rhetorical model of an interconnected, networked system of care may look like. Despite its problematic characterization of patients as operating at a literacy deficit, the model also emphasizes the role of the system in making itself more transparent and more supportive of patients. The Health Literate Care Model begins to envision networks of care that are not tied solely to payment/profit; specifically, the community care coordination piece of the model is a first step towards an understanding of health and wellness beyond the biomedical model of health, or framing health through the testing, diagnosis, and treatment we receive in the clinical setting (Segal; Stone; Engel). Community care coordination extends the work of clinics and health professionals to build their care planning together with communities and caregivers.

Toward Networked Caregiving as Literate Activity

To illustrate how a community literacy model may aid in the re-framing of health literacy toward health literate practices, I return to the community care coordination project in which I am involved in mid-Michigan. This project began as I volunteered at a local legal aid clinic for older adults. A lawyer in that clinic had been in conversations with his clients for over twenty years, conversations in which older adults expressed needs for health and human services (Medicare claim disputes, Medicaid waiver eligibility for long-term care placement, SNAP food assistance, etc.) as well as legal assistance. He then sought to develop better lines of communication across all of these sectors, as well as with older adult clients/patients and caregivers. When I also began working at the community hospital, we sought to network all of these actors into an online platform where screening for resources, referrals, and care plans might be coordinated.

This networked platform in an example of a community computing project. Jeffrey T. Grabill identified community computing as an area of community-literacy study that focuses on “the implications of the interactions between information technologies, writing, and public institutions” (9). An example that he gives, building databases for citizen action, is not unlike how we began this project. Part of the benefit of a care coordination tool for all involved was the creation of a continuously crowdsourced, updated database of available community resources in our area for older adult patients. Currently, no such resource in our area exists, other than a phonebook-style physical directory and face-to-face community resource fairs each year, and these were available to professionals only, not to caregivers or patients.

Community computing as community literacy emphasizes that data democratization is an essential component of activism (Grabill). This project accomplishes this in two ways. The first is the database itself, necessary to search for community resources and visualize the network of what services exist in our region and which do not. This creates a data-driven approach to advocacy, in that we can also see what we lack by which organizations do not appear. Further, a networked technology can show the human services sector what services are being searched for. The data collected from the tool enables new ways of seeing resources and lack of resources for older adult patients in our community. In the ways that the healthcare system wishes to harness that data for cost control and savings, the human services and nonprofit sector can harness it for advocacy, for grant writing, and to make better evidence-based arguments more about resources and supports and their impact.

A community-driven approach is what makes this project a community computing project. While there are proprietary software tools on the market that do similar work as our community care coordination tool, the goal is not to democratize data, but to store, silo, and sell it. The most important aspect of this project for our team is that every community partner can, without cost, participate and use their usage data: number of searches that yielded their agency, number of referrals made, health outcome data, and so on. For organizations that, for example, provide free diabetes management education in rural areas, an understanding of how that education affects health outcomes is critical for their program evaluation, and, ultimately, their sustainability as a free community resource. Therefore, the creation of these networked writing spaces is not only creating space to support the patient, but to support the fabric of the community.

While this networked tool and its use continues to evolve through several pilot studies, I would like to suggest three examples from this project that highlight moves away from the rhetorics of health literacy toward distributed health literate activity for older adults and caregivers. All three aim to uncover Prior’s “cultural spheres of literate activity” in healthcare settings and in homes and communities, such that a more complete and positive view of aging and interdependence might be facilitated in the healthcare system.

1. Feedback from older adults and caregivers as to the creation of spaces for literate activities that reflect their desired experiences

As scholarship in age studies demonstrates, older adults as well as caregivers articulate their lived experience with the healthcare system as marked with frustration, discomfort and stigma, due to lack of trust in healthcare providers with sensitive issues (Greene and Adelman) and to difficulty navigating the complexity of the system (Garner and Faucher). Rather than create a system of communication that reinforces these difficulties, we have sought the feedback of older adult patients and caregivers in our legal and healthcare clinic sites to better understand how they might feel comfortable locating and coordinating resources for care, or having these located and coordinated on their behalf. This feedback overwhelmingly suggests, as age studies scholars Anne Glass and Rebecca Vander Plaats contend, that “social networks and improved health outcomes are strongly connected” (428). Further, while these social networks can be family, friends, faith community, or other personal ties, we might also seek to network caregivers in community, home, and health contexts who are known to one another, rather than sending patients and caregivers home to seek help alone by cold-calling phone numbers on brochures. Because the healthcare system privileges the doctor-patient encounter and relationship, a networked, distributed approach to coordinated care presents a cultural departure but one that better reflects the desires and well-being of older adult patients and caregivers.

2. Facilitation of dialogue across cost-based health systems and mission-driven community organizations who serve older adult patients/clients

As Linda Flower writes, “the local, intercultural publics of community literacy work by circulating new models of dialogue across difference” (6). In order to change the ageist belief of older adults placing the healthcare system in an economic crisis, as well as the correlated belief that health care is an independent, individual responsibility on the part of the patient, new spaces to dialogue are needed. Community-literacy studies offers a framework to dialogue across those who hold these ageist and individualistic beliefs and those who are focused on a humanistic view of aging that integrates cultural and social dimensions of care and caregiving. The health system and its representatives hold very different beliefs about responsibilities for care in community contexts than mission-driven health and human services organizations. My work, first and foremost, was not to provide any answers about how to write community care coordination, but to create spaces for the dialogue to take place across these very different stakeholders to the conversation. Through public forums, private meetings, conference calls, one-on-one conversations, group emails, and scattered other forms of communication, we began to build a network of professionals and caregivers who could find common ground and begin to see their work, their literate activity, as shared.

3. Explicit involvement by patients, caregivers, and community sources of support in care plans for older adult patients

Creating an alternative to both (1) the rhetoric of a skills-based health literacy of the individual older adult patient and (2) biomedical models of diagnosing and treating the declining health of the older adult body are crucial to the cultural shift to acceptance of interdependence and distributed health literate activity. The care coordination project seeks to find a method for the highly distributed and collaborative work of caregiving that puts on an equal footing clinical care and home and community care. In order to do this, home and community contexts must be made visible in ways that they currently are not in clinical medical practices and electronic medical records. The community care coordination tool creates a more accountable digital space in the clinic where representatives from the home (patient or caregiver), community (health and human services professionals), and clinic (provider) all participate to plan coordinated care together.

Caregiving is often hidden in plain sight across the lifespan. While we care for others in our homes, and others care for us at various points in our lives, we rarely publicize it in the same way that we do our educations or careers. What is more often the case is “this work”—and self-management of chronic illness is indeed work (Arduser) is also unpaid labor for informal caregivers—family, friends, and community members who have other careers but also provide care (assuming the patient has this system of support in place, and many do not). Others have formal caregivers who may be paid but are not visible, permanent members of the home. What the care coordination tool project does is make visible (and quantifiable) the extent of this work to healthcare professionals and other stakeholders, showing them how much of the work to get or stay healthy often falls far outside of the prescription pad, and on the shoulders of those who do not stand to financially benefit. It also renders visible the distributed, networked literate activities of the many caregivers—professionals, relatives, friends, and patients—giving and receiving care across the lifespan. This looks much different than the rhetorical construction of health literacy that currently circulates.

As teachers and scholars of writing, we can create more visibility for caregivers and the complex ways care might be enacted. The community care coordination project is an example of how we might envision a notion of health care that is networked, distributed, and collaborative—socially-constructed rather than individualistic and skills-based. Caregiver relationships demonstrate how interdependent literate care practices truly are. As compositionists, we can support the creation of networks of writing, through facilitating database creation, through technology training, and as advocates for the writing work that is so vital for healthcare and community professionals as well as patients and caregivers to undertake in order to improve patient health outcomes. Building these rhetorical models requires collaboration across industry, community, and the academy, and while that coordination is difficult, it is of great cultural and social value. This resembles other community literacy projects (Grabill; Flower) and community-engaged writing collaborations in the field of composition studies (see, e.g., Rumsey et al.). This work also aligns well with critical and humanistic gerontology’s turn to feminist perspectives of power “by stressing social relatedness, community good, and interdependence rather than individual good and independence” (Minkler 472). For literacy scholars, age studies scholars, and compositionists alike, the networked writing work of community care coordination presents an opportunity to reframe health literacy rhetorics and act for change.