Abstract

Contact zones are useful for literacy research because they foreground the contexts that recent decades of literacy studies scholarship have deemed essential: history, orality, language difference, and power, with an emphasis on interaction rather than divides. While literacy studies has demonstrated the importance of these contexts for understanding literacy, there is not yet a model that organizes them into a framework for research. Compositionists have paved the way for understanding contact zones not just as spaces to observe and describe but also as spaces in which challenging learning and instruction can occur. In a contact zone, different languages interact through writing, reading, speech, and other expressions because of historical circumstances and with greater and lesser privileges afforded to them on account of these historical circumstances. A literacy contact zone approach calls for researchers to account for the oral, linguistic, historical, and differential power contexts for the literacy phenomenon under investigation.

Keywords: contact zones, literacy research, conceptual framework, contexts

Contents

Contexts and Models in Literacy Studies

From Great Divides to Contextual Dynamics: Literacy Studies Research on History and Orality

Introduction

The past few decades of literacy studies research have shown that literacy is inextricably related to history, speech, power dynamics, and language ideologies. However, few widely used conceptual frameworks for literacy research articulate these principles. To address this gap, I propose employing the linguistics concept of contact zones as a conceptual framework for literacy research because it foregrounds the contexts that have proven essential to literacy studies scholarship. These contexts are language diversity, history, orality, and power at more targeted and wider-ranging scales of focus. Mary Louise Pratt famously described contact zones as “social spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination—such as colonialism and slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out across the globe today” (Imperial Eyes 7). This concept of contact zones has been used to theorize the political and power disparities present in sites—such as texts (Pratt) and classrooms (Lu)—where such influences might not be visible. A literacy contact zone framework for research would orient investigations of literacy in sociolinguistic and history-rich contextual understandings that assume asymmetrical power dynamics. Contact zones also have the benefit of several decades of debate in the field of composition, which has revealed the limitations and affordances of the concept for learning environments. As a model adopted from linguistics, contact zones are relevant to the often interdisciplinary and multi-sited research in literacy studies scholarship.

Contact zones, re-infused with their linguistic origins, articulate a concrete context in which literacy and literacy instruction exists and where language difference, orality, history, and power dynamics are at the forefront. They thus call for researchers to account for these contexts when studying literacy. In the humanities, contact zones originated in contact language and linguistic analyses. Pratt developed the idea of contact zones into an analytical tool for literary and comparative studies, and it quickly spread to other fields of study. Composition scholars have paved the way for understanding contact zones not just as spaces to observe and describe but also as spaces in which counterhegemonic learning and instruction can occur. I draw upon the work of Pratt and composition studies, which treat contact zones as a metaphor for observing other discursive phenomena, but I also connect contact zones to its even more concrete meaning for linguistics research in language contact and creolization. In a linguistic contact zone, different languages interact via writing, reading, speech, and other expressions. These interactions are inextricably connected to economic and geopolitical forces and have greater and lesser privileges afforded to them on account of these historical contexts.

This essay begins by tracing studies that have established essential contexts for responsibly understanding literacy. I argue that these seminal works particularly highlight the importance of history and orality contexts, which are two of the contexts I propose taking up in a contact zone framework for literacy research. I next turn to composition studies, where scholars have teased out useful lessons and cautions about using contact zones as a metaphor for writing classes. This section brings to light what compositionists have revealed about the significance of language differences and power dynamics, which are the third and fourth contexts I attribute to a contact zone framework. A final section provides a brief glance into three literacy contexts in which a contact zone analytical frame illuminates potential blind spots in the complex situations surrounding literacy and literacy instruction: UNESCO’s website, a popular literacy campaign in Nicaragua, and the languages of schooling in Haiti. By building this model of contact zones with history, orality, language difference, and power dynamics as central contexts for forging literacy research, I aim to capture important contributions from different disciplines to the study of literacy. I further hope to reinvigorate the concept of contact zones by emphasizing its sociolinguistic roots, in which contact zones represent actual spaces of language and other exchanges rather than metaphors of interaction and conflict.

Contexts and Models in Literacy Studies

Scholars have examined literacy through the lenses of language difference, orality, history, and power dynamics since the late 1970s. Rather than propose a new approach to literacy research, I argue that a contact zone framework brings together the analytical insights that have been successful in the field of literacy studies. That is, insights about literacy ranging from identifying research methods for teachers to better understand their students’ language backgrounds to distinguishing between the effects of schooling and literacy are only revealed through careful attention to linguistic, historical, oral, and power-dynamic contexts. Shirley Brice Heath carefully documented the oral language practices and differences of Trackton and Roadville Carolina residents when she was tasked with advising elementary school teachers to work with a newly integrated student population in Ways with Words. Sylvia Scribner and Michael Cole studied literacy instruction among the Vai in Liberia. They performed tests for certain cognitive functions and determined that schooling had a greater impact than literacy on abstraction, memory, logic, taxonomic categorization, and perceived objectivity of language. Robert F. Arnove and Harvey J. Graff’s edited collection of literacy campaign research attested that the desire to transform and reform a population through literacy instruction dates back at least to the Protestant Reformation’s push to provide biblical instruction in the contemporary standard German language rather than Latin. Today’s mass literacy campaigns contain similar appeals to the “power” of reading and writing—and even mathematics and computer programming —to overcome social, political, and geographic exclusion as well as economic inequalities.

As research in literacy studies continues to draw upon and impact work in multiple disciplines, several prominent scholars in the field have called for new organizing models. The argument I make here for a contact zone framework for research recognizes the exigency for advancing best practices in literacy research with a concept that can renew the focus on important contextual details related to literacy and issues of power. Some of the more recent models for literacy with a similar aim include David Barton’s ecological literacy, Fernandez’s rhizome, and Jan Blommaert’s grassroots literacy.These concepts have made headway towards disrupting simplistic patterns of analysis, and I propose a contact zone framework with a similar result in mind but with a particular interest in making the contexts of literacy research both conceptually concrete and interactive rather than fixed.1 The inaugural issue of Literacy in Composition Studies (LiCS) showcased scholars from across literacy- and composition-related fields and methodologies who surveyed research questions and tensions that came before and pointed towards future inquiry. Each of the symposium and symposium response articles stressed the importance of context, whether that referred to location in or outside of school, national borders, history, ideology, or power. Their discussions emphasized several of the contextual focuses this article proposes to highlight with contact zones, including power, history, language and literacy diversities, and avoiding exaggerated divisions like literacy/orality (see especially Graff; Viera; Flannery; Parks; Trainor; and Qualley). Steve Parks called for “a different model” for characterizing literacy’s dynamic embeddedness (43). Donna Qualley moved most clearly towards a framework that avoids “the mental inertia,” which occurs, as she explained, “[w]hen our terms and concepts no longer function as threshold concepts, portals that enable further movement” (50-51). Qualley suggested that Hilary Janks’s “four orientations” offer some guidance for scholars of literacy and composition. These are domination, access, diversity, and design (Qualley 51). By keeping these orientations equally in sight, researchers can combine the expertise of both literacy and composition studies. (Qualley extended Janks’s warning that leaving out one orientation skews the balanced picture of literacy). This is a promising direction that articulates a clear set of tensions emerging from research insights and also pushes back against scholarly blind spots. I wish to continue this conversation in LiCS about seeking productive frameworks that can jar researchers out of conceptual theoretical ruts and “divides” related to literacy by exploring what sets of tensions emerge, what “traps” can be avoided, and what connections can be created between literacy and composition studies if we take contact zones as a framework for literacy research.

Recent research in literacy studies has reinforced the importance of place—geography, physical location—for interpretations of literacies. Two studies in particular have sought to renew attention to place as an important context for understanding literacy in school achievement and in implementing learner-centered pedagogy in Tanzania. These educational researchers emphasized tensions similar to contact zones under different conceptual models. Jerome E. Morris and Carla R. Monroe argued that studies of educational achievement by African-American students must consider the “race/place nexus” and, in particular, understand “the South as a critical racial, cultural, political, and economic backdrop in Black education” (21). They demonstrated that closer attention to language patterns, “geographies of opportunities,” historical migrations, and factors that shape regional identities lead to richer understandings of education research. They also implored scholars to “ground their studies in comprehensive analyses of the social contexts in which student achievement occurs” (31). Literacy contact zones demand precisely this sort of grounding, building upon best practices in literacy studies scholarship. Morris and Monroe’s “race/place nexus” highlights some of the tensions that Lesley Bartlett and Frances Vavrus developed with their “vertical case study” conceptual framework for research. The vertical case study entails a three-part analysis, which includes, “a ‘vertical’ attention across micro-, meso-, and macro-levels, or scales; a ‘horizontal’ comparison of how policies unfold in distinct locations; and a ‘transversal,’ processual analysis of the creative appropriation of educational policies across time” (Bartlett and Vavrus 131). While the name “vertical case study” is a bit misleading given the equally important “horizontal” and “transversal” components, this framework invites research strategies as robust as Morris and Monroe’s call for more in-depth discussion of region and identity. A literacy contact zones framework insists on a similar attention to multiple levels of context, comparison, and history but also accounts for interaction, a distinction I develop below. Keeping these models of richly contextualized literacy investigations in mind, I offer contact zones as a framework for understanding the complex contexts in which literacy exists.

From Great Divides to Contextual Dynamics: Literacy Studies Research on History and Orality

Among the most lasting legacies of literacy studies scholarship are ongoing projects to reject arbitrary divides. In the late 1960s and 1970s, scholars began to earnestly reject exaggerated claims about the separateness between literacy and orality that overstated literacy’s singularity among other unhelpful assumptions. They urged instead for investigators to see literacy in two overlooked contexts: history and orality. Researchers in anthropology, history, and linguistics sought to complicate the “great divide” between literacy and orality, especially as conceived in the 1960s by Jack Goody and Ian Watt. Kate Vieira has since noted that Goody and Watt themselves were responding to the challenges that writing posed to traditional divides between anthropological and sociological research. To Goody and Watt, discussing literacy and non-literacy could address the political backlash to the terminology of “primitive” and “civilized” (Vieira 26). Brian Street offered his concept of “ideological literacy” in response to studies by Goody and Watt, Walter Ong, David Olson, Eric Havelock, and others who claimed that literacy had significant impacts or “consequences” on the human psyche. Arguments such as those made by Goody and Watt claiming, “one invention, the invention of writing, . . . changed the whole structure of the cultural tradition” (67) fell under Street’s “autonomous” model of literacy. Such arguments relied on a notion of literacy as superior to orality and as having universal “consequences” on persons and societies who become literate apart from the contexts, beliefs, and meanings ascribed to literacy. As an alternative to this, Street proposed a view of literacy as “ideological,” which highlighted “literacy practices as inextricably linked to cultural and power structures in society and [encouraged researchers] to recognise the variety of cultural practices associated with reading and writing in different contexts” (“The New Literacy Studies” 433-34). With a similar concern, Harvey J. Graff looked at archival data in nineteenth-century Canada and further disproved such “consequences” of literacy, proposing instead the existence of “literacy myths.” Recognizing myths and ideologies points us towards more nuanced understandings of the connection among different literacies and their social, historical, political, cultural, and economic contexts. Contact zones point in even more direct ways to specific contexts that literacy researchers have sought to make central to literacy investigations. Furthermore, a contact zone framework focuses on the interaction of elements that have historically been separated by scholarship, including orality/literacy and local/global/translocal components related to literacy.

Before looking at other studies of literacy in oral and historical contexts, I want to note that Street’s rejection of direct and reliable “consequences” for literacy potentially creates a new divide between “autonomous” and “ideological” literacy models. Unlike orality and literacy, whose division leads us to ignore the interrelation between them, the distinction between autonomous and ideological paradoxically asks investigators to understand that literacy is actually always ideological while proposing “autonomous” as a model for (falsely) decontextualized literacy. Linguistic anthropology faced similar conceptual and terminological limitations in the 1990s, when observers were too quick to accept complex notions of “culture” and “language” as the results of neutral or “natural” processes. Reflecting on the emerging response to this trend, Kathryn A. Woolard and Bambi B. Schieffelin suggested that to counter the “naturalizing move that drains the conceptual of its historical content”, language theorists should embrace “the term ideology [which] reminds us that the cultural conceptions we study are partial, contestable and contested, and interest-laden” (58). Street offered a similar intervention but introduced the term “autonomous” to label an inaccurate treatment of literacy characterized by viewing literacy out of context. In Street’s words, “[t]he skills and concepts that accompany literacy acquisition, in whatever form, do not stem in some automatic way from the inherent qualities of literacy, as some authors would have us believe, but are aspects of a specific ideology” (Literacy 1). When authors make claims about literacy’s impacts apart from contexts and beliefs, they are also under the influence of ideology: “[t]he ‘autonomous’ model is […] constructed for a specific political purpose” (Street 19)2. In spite of such claims, then, autonomous discussions of literacy do not escape the ideological contexts that inform all interpretations of literacy.

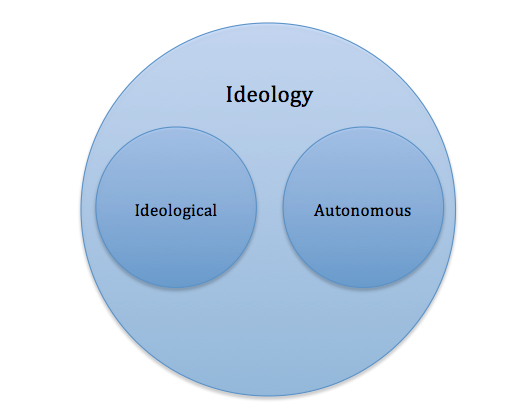

In Figure 1, I illustrate what Street’s conceptual framework entails. Bruce Horner captured the complexity of this theoretical move: “the autonomous model is powerful in claiming an autonomy for literacy that hides its ideological character, purporting to offer literacy as an ideologically neutral phenomenon” (1). Horner continued: “[b]y contrast, what Street calls the ‘ideological’ model of literacy takes the ideological character of all literacy and its study, and hence takes conflict, as inevitable givens” (Horner 1). Subsequent studies have found Street’s “ideological” literacy model useful for framing an interrogation of beliefs about literacy (see recent works by Budd et al. and Camangian). Like most scholarship on literacy since Street, Graff, Heath, and others challenged these unquestioned beliefs about literacy, a contact zones framework acknowledges that all views of literacy are ideological. Rather than discuss autonomous literacy as distinct from ideological literacy—since Street and Horner tell us that both are ideological—a contact zone analysis engages history, orality, language difference, and power as contexts for literacy to help researchers delve into the specific workings of ideologies. If we look historically at literacy, what Street described as ideological literacy is the only responsible way to characterize the various uses, concepts, and pay-offs literacy has held throughout history.

Figure 1. Visualization of Street’s ideological and autonomous literacy.

Since Goody and Watt, a number of important studies of literacy in specific contexts have highlighted the erratic uses and values of literacy historically, all of which point to the ongoing relationship between literacy and orality and ultimately the importance of attending to history. Old Testament scholar David Carr has demonstrated that for ancient Israelites, literacy could not be entrusted with the important task of transmitting religious teachings to future generations in the ancient Near East. Though it appears logical, by today’s understanding of written records, that such texts could effectively pass on teachings, Carr asserted that for the Israelites, “[w]ritten copies of texts served a subsidiary purpose . . . as numinous symbols of the hallowed ancient tradition, as learning aids, and as reference points to insure accurate performance” (18). Writing did not supplant orality in the ancient Near East, and thus literacy was only necessary as a subset of learning skills focused more on memorization. This correlates with William V. Harris’s research in ancient Greece and Rome. After taking into account a variety of “economic, social or ideological” and political “forces” in the ancient Greco-Roman world, Harris argued that such “vital preconditions for wide diffusion of literacy were always absent” (12). Further, Harris suggested, “In most places most of the time, there was no incentive for those who controlled the allocation of resources to aim for mass literacy” (13). Studies of medieval uses and treatments of literacy by Michael Clanchy, Joyce Coleman, and Ruth Finnegan also offer evidence of the persistence of orality and halting adoption of writing in specific historical contexts.

These early examples of emerging roles for writing remind us that literacy did not supplant but rather interacted with and depended upon orality. Literacy had to gain use-values in every context in which it eventually thrived. If researchers look for both, they will find literacy interacting with speech in instruction, reading performances, and everyday negotiations of texts’ meanings and contexts. A contact zone framework calls for attention to both history and orality. Language contact occurs because of socio-historical events and happens through verbal exchanges. If literacy is viewed as embedded in contact zones, then researchers must search beyond accepted beliefs about writing and literacy instruction. Looking at oral and historical contexts raises questions of interaction rather than division: why does a particular literacy, genre, or text hold significance for a group of people?

Even with this brief glance into the early involvement of literacy in people’s lives, we can recognize a stark contrast between the somewhat ambivalent entry of literacy into these ancient and medieval societies and today’s widespread enthusiasm for literacy. Unlike ancient and medieval incorporations of literacy into religious and practical contexts dominated by non-written approaches, literacy has become a quality valued not just for specific activities in context but as a status so desirable to philanthropic groups and individuals that it mobilizes global initiatives. Studies by Mary Jo Maynes and Harvey Graff have shown that by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, literacy took on more lofty and abstract notions. Indeed, literacy was sufficiently isolated from immediate contexts and particularities by the 1960s that scholars could publish serious studies about the role literacy played in bringing about democracy and modern notions of reflectiveness and critical thinking (Goody and Watt; Ong; Havelock). Of course, literacy’s meaning always depended on the values and associations of literacy with notions like “progress” held by institutions and communities (Graff). The longer history of literacy should give scholars pause before isolating literacy from its current and historical oral surroundings.

One significant call for change in our conceptions of literacy and scope of research was Deborah Brandt and Katie Clinton’s article “Limits of the Local.” As their title suggests, Brandt and Clinton challenged the trend that emerged in response to the universalizing gestures in scholarship by Goody and Watt, in which researchers sought to document local literacies or literacies in more targeted contexts. In this critique, the authors attempted to disrupt an emerging “great divide” between local and global contexts for literacy (338). To do so, they reconfigured Street’s term “autonomous” to describe not the elision of context from a discussion of literacy but autonomous literacy as a “transcontextual” component of literacy that spans multiple locations. They proposed “to grant the technologies of literacy certain kinds of undeniable capacities—particularly, a capacity to travel, a capacity to stay intact, and a capacity to be visible and animate outside the interactions of immediate literacy events” (344). Seeking the transcontextual “thingness” of literacy is an intriguing move for literacy researchers to make insofar as it enables a view of contexts for literacy that feature interactions between peoples, media, ideologies, and other exchanges within and across communities. However, in highlighting the ways literacy is infused with specific and immediate uses and practices as well as more wide-ranging significances, Brandt and Clinton raised questions about this new autonomous literacy’s relation to Street’s original configuration. Is autonomous literacy decontextualized or transcontextual? Does literacy have to lose its contextual meanings in order to travel? Street himself urged those who used Brandt and Clinton’s work to examine “distant” literacies rather than autonomous ones. In “Limits of the Local: ‘Autonomous’ or ‘Disembedding’?” Street argued that “[t]he features of distant literacies are actually no more autonomous than those of local literacies, or indeed than any literacy practices” (2826). In other words, literacy already has a transcontextual “thingness,” or meanings that do not wholly derive from an immediate or “local” context. Rather than assign literacy a transcontextual label, we might ask what seems to hold true about literacy practice, literacy’s relationship to orality, and literacy’s perceived value across contexts? Such questions highlight interaction within context—central features of a conceptual space like a contact zone that is defined by speakers of different languages communicating using varieties of resources. The focus on interaction again avoids pitfalls of the second “great” divide that Brandt and Clinton identify in literacy research between “local” and “global” contexts and phenomena. As with orality and literacy, “local” and “global” are terms that describe different features of social experiences. Differences related to literacy and geographic spaces do exist, but “global” and “local” have become exaggerated categories that prevent more dynamic understandings of circulations and scales related to literacy.

To demonstrate the limitations I find in the above concepts, I will turn briefly to a narrative that illustrates a belief about literacy that, while not supported by research, nevertheless had real consequences for the people involved. In March 2015 I interviewed a primary school teacher in southern Haiti as part of my research on literacy volunteer preparation. My interview questions focused on what the interlocutor thought would best prepare someone from outside of Haiti to work with Haitian teachers. I ended each interview with questions about the number of children who attended school in the area, how many of their parents might have attended school, what people in the area read and wrote, and so forth. This particular teacher shared a story in response to my question, “if I were an adult living in this area, what kind of things would I need to be able to read and write?” After offering some examples of landowners throwing away deeds and difficulties conducting and documenting vending at the market, she told me about her mother, who was a highly regarded servant for a woman in the nearby city. That woman’s sister lived in Miami. When the sister came to visit them in Haiti, the sister was impressed with the servant and wanted to take her, the interlocutor’s mother, to Miami. Here is our interpreter’s explanation of what happened next:

But she couldn’t or she didn’t [take the mother to Miami] because she didn’t know how to read and write. So that’s—that has a major impact on her. […] She said that that was a big loss for her. That was probably the biggest loss because everybody wants to travel. […] She [the interlocutor] said even herself, then she wouldn’t be born here she would be born—. Yeah, yeah, she said she doesn’t regret that she’s Haitian, but she would’ve been born in a different country. Because of that, then, the husband of the lady at whose house she was a servant decided to sell her. (Primary schoolteacher, Personal interview)

Not being able to read and write for this interlocutor meant that her mother missed an opportunity to travel and perhaps even relocate to the United States. Insufficient literacy in this case truly changed the life of the mother, who even lost her job as a result of the interaction with the Miami-based relative of her employer. There is much to unpack here.

This story may appear to demonstrate Brandt and Clinton’s view of autonomous aspects of literacy that can be “transcontextual.” Actual travel—a politically significant 650-mile trip across the Caribbean—is linked directly to literacy, but literacy does not work here as Brandt and Clinton suggest, with “a capacity to travel, a capacity to stay intact, and a capacity to be visible and animate outside the interactions of immediate literacy events” (344). What is traveling and influencing travel is a belief about literacy—a literacy myth through which the sister from Miami equated some level of skill in reading or writing with the ability to succeed as a domestic employee. I don’t think we can characterize this story as representing autonomous understandings of literacy in Street’s definition of autonomous: “broad generali[zations],” “assum[ing] a single direction” for “literacy development” and “individual liberty and social mobility,” or as “isolate[ing] literacy as an independent variable and then claim[ing] to be able to study [or know] its consequences” (Literacy 1-2). The belief that literacy was a stipulation for bringing this Haitian worker to the United States as a personal employee is heavily dependent on context —even if this was an excuse for other reasons this person had to deny taking the worker to Miami. Indeed, the two sisters clearly differed in their views about whether literacy was necessary for a domestic worker though they appear to have shared similar appreciation for this worker’s other qualities. Configurations of power across class, nationality, and gender are central to this context (it is intriguing that the storyteller attributes her mother’s dismissal by the husband of her employer to the rejection by the Miami-based sister). History is equally important, including the relationship between Miami (and the U.S.) and Haiti, the geopolitic that contribute to Haiti’s current political and economic situation, and the different social values of work and vocations.3 As another example at the end of this essay will demonstrate, language difference and orality are particularly important for understanding literacy in Haiti. However tacit and unspoken such contextual factors may be, I do not take this story’s literacy myth or belief to constitute the denial of context or ideology.

Literacy research needs a new model that articulates the underlying methodological perspectives that the field has developed from multiple disciplines, including attention to history, language differences, orality, and power. Apart from compelling researchers towards rich descriptions of contexts, contact zones can connect literacy scholarship to practice through their applications in writing classrooms by composition studies.

Composition scholars have used contact zones to think about classrooms, curricula, and texts in ways that highlight language differences and power dynamics. Their theorization of contact zones for writing instruction opens additional paths for literacy researchers to apply a contact zone framework to discuss literacy instruction in addition to literacy practices. Contact zones entered academic conversations in the 1990s as a cross-disciplinary concept that was quickly taken up by writing instructors. Mary Louise Pratt drew upon a creole linguistics concept to propose that interpreting travel writing produced in multicultural colonial spaces entailed examining the “arts” of contact zones. Following Pratt’s suggestion in 1991 to “[look] for the pedagogical arts of the contact zone” (40), compositionists evaluated the merits of using contact zones as a framework for thinking about language difference in classrooms, inclusive literature curricula, and hostile viewpoints in student writing (Canagarajah; Bizzel; Miller). This was a robust (and ongoing) discussion that stemmed from the cross-disciplinary orientation of contact zones themselves. For composition pedagogy, contact zones have been a productive locus upon which to resituate and rethink multiple student competencies and language differences in the classroom. Such conversations would be useful for the field of literacy studies, which has been grappling with similar contentions and contradictions regarding diverse language speakers and privileged literacies (Kynard; Young; Canagarajah; Lu and Horner). In addition, compositionists, building on Pratt’s application of contact zones to historical and colonial texts, have shown that contact zones can apply to contexts dealing with legacies of colonialism across the globe, including classrooms in the present-day United States.

Pratt offered her model of contact zones to instructors of literacy as an alternative to what she viewed as a homogenizing model of “community” in instructional theory and practice (“Arts” 34). It was Pratt’s 1991 speech and essay “Arts of the Contact Zone” that commanded composition scholars’ attention in particular. As with her view of literary texts (expressed in a similar quotation above), Pratt argued for a vision of classrooms and school-based writing as “writing and literacy in [. . .] social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out in many parts of the world today” (34). The “literate arts of the contact zone” referred to works from a number of marginalized writers as well as to genres like parody, critique, autoethnography, and transculturation (36). Such writing risks miscomprehension, becoming “unread masterpieces,” and “absolute heterogeneity of meaning” (36). Students enter classrooms with multiple identities, interests, and historical relationships to texts and to one another. To seek homogeneity or “horizontal alliance” in a classroom is to ignore and erase these differences and to subscribe to an academic vision of Benedict Anderson’s “imagined community” in which “universally shared literacy is also part of the picture” (Pratt 38). Pratt encouraged instructors to resist projecting such a leveling community in the classroom by selecting a variety of dominant and non-dominant texts and to search for pedagogies that consider cultural mediation and facilitate multiple encounters with the “ideas, interests, histories, and attitudes of others” (40). With this, Pratt ignited a series of debates and questions regarding the uses and limits of contact zones in classrooms.

For the field of composition studies, contact zones offered a useful language-based concept for generating questions about pedagogy and language difference that engaged issues of history and power. Composition studies in the 1990s featured debates about whether writing classrooms were becoming spaces for instructors to spread “dogma,” “politics,” “ideology,” and their own “social goals” instead of what Maxine Hairston suggested as a preferable focus: “diversity,” “craft,” “critical thinking,” and “the educational needs of students” (698). Calls to separate politics from writing instruction came amidst discussions of new models for composition in multimodal formats, the ongoing challenge of the 1974 Conference on College Composition and Communication resolution to affirm “Students’ Right to Their Own Language,” and renewed outcries about literacy “crises” (Gee 29). The benefit of contact zones since their introduction in composition studies is that they call attention to the complex political and social histories surrounding language difference and remind us that the choices that individuals make in writing, speaking, and design involve unequal access to power.

College writing classrooms became an area where discussions of contact zones facilitated important questions in the theory and practice of composition. In her landmark essay, “Professing Multiculturalism: The Politics of Style in the Contact Zone,” Min-Zhan Lu described a classroom discussion about a piece of student writing that included the non-standard construction “can able” in an essay. Her article shows that Lu achieved several aims of Pratt’s somewhat elusive “pedagogical arts of the contact zone” (Pratt 40) by assigning Haunani-Kay Trask’s “From a Native Daughter” and by assuming (and encouraging) students’ own non-standard usages to be intentional meaning making choices. Lu then invited other students to consider the rhetorical effectiveness of the “can able” usage and asked them to suggest whether the writer should keep it or how to change it for a particular purpose. By bringing this text and its multiple meanings into the classroom for serious critical discussion instead of ignoring or offering a more standard version of the construction, Lu created a space that allowed for multiple voices in writing and for negotiation and dissent—grappling—with how to write and read in a contact zone.

Other considerations of contact zones in the classroom explored both the opportunities and challenges that this concept offered when it was used, following Pratt’s lead, as a metaphor. Patricia Bizzell proposed to arrange English courses around “historically defined contact zones, moments when different groups within the society contend for the power to interpret what is going on” (483). Cynthia L. Selfe and Richard J. Selfe leveraged the colonial critique central to contact zones to teachers and programmers of digital interfaces with the aim of “identify[ing] some of the effects of domination and colonialism associated with computer use” (482). Richard E. Miller prompted contact zone enthusiasts to consider their “competing commitments” to contact zone-style grappling when confronted with student writing and opinions expressing violence or hatred towards a group of people (392). Suresh Canagarajah’s application of contact zones in college writing classrooms considered the role of safe houses and language use in written and online student communication. He suggested that students from historically marginalized communities do not uniformly resist dominant discourses and literacies but that they learn accommodation practices as well. Canagarajah pointed out the differences between the way the students in his “college preview” summer class deployed resistant, vernacular, and multi-vocal writing in the class’s online forum but not in other writing for the course. Despite his attempt to encourage students to use the languages in which they felt most confident in their formal written assignments, Canagarajah saw the students deploy much more typical academic approaches to writing. He posited that students utilized a kind of “fronting” in leaving behind vernacular uses for language they saw as more academic. Both Lu and Canagarajah took seriously their students’ diverse literacies and range of options for writing. Contact zones have been sources of dialogue and debate about what to do with difference in classrooms but have not resolved these concerns. Contact zones do, however, offer a framework for bringing these differences into the foreground and for attending to the historical contexts and “asymmetrical relations of power” (Pratt 34).

Like Miller, Joseph Harris raised important questions and critiques of contact zones. Harris listed his concerns that contact zones emphasize division amongst students and distance students from one another, raise difficult practical questions for teachers, invite superficial encounters, and “romanticize the expression of dissent” (165). Rather than emphasize difference and conflict alone, Harris proposed the city as a model for recognizing difference, one within which teachers could “[urge] writers not simply to defend the cultures into which they were born but to imagine new public spheres they’d like to have a hand in making” (169). A city, unlike a contact zone, invites “allegiance” and gives people who may be very different from one another a reason to work together (163). Harris’s model of a city has several strengths. Like contact zones, cities are inhabited by diverse populations. Unlike communities, which both Harris and Pratt reject, cities and contact zones don’t assume resolution is the end goal of teaching, writing, or classroom discussions. To address these valid concerns while retaining the productive challenges to “[treat] difference as an asset, not a liability” (Bizzell 483), discussions of contact zones would benefit from considering the sociolinguistic origins of Pratt’s concept. Part of the clashing and grappling involves linguistic innovation and incorporation across differences (Nelde; J.G. Heath; Darquennes). These negotiations continue to occur because speakers of different languages continue to interact. Writing and literacy instruction takes place in these dynamic oral contexts, which need not be treated metaphorically—researchers in composition as well as literacy can look for the historical, oral, language diverse, and power differentiated contexts that surround actual instruction and practice.

Contact zones continue to be a relevant and challenging model for understanding the contexts and possibilities of language and literacy differences in composition as well as literacy, but using contact zones as metaphors can be limiting. Ellen Cushman and Chalon Emmons used Pratt’s concept of contact zones to theorize a service-learning course in which their students worked with a local YMCA. Cushman and Emmons defined contact zones somewhat narrowly as a proxy for cross-cultural engagement, using Pratt’s model. The authors’ critiques point to an important limitation of only using Pratt’s definition of contact zones. Cushman and Emmons explained their concern with Pratt’s contact zones, which could cause “[t]exts and class discussion about them [to] become the operative means for providing ‘contact’ with other value systems” (204). While Canagarajah and Lu would view the classroom with students reading such texts as already a contact zone, Cushman and Emmons focused on the texts as creating a contact zone. This more specific application of contact zones to learning environments led Cushman and Emmons to intervene in contact zone theory. They saw the harmful potential for “superficial social interaction” in which readers have little stake in engaging with the “grappling” and negotiation of contact zones produced by texts. As an alternative, they suggested that community engagement created a more immediate context for interaction across social differences and for experiential learning (205). Their title, “Contact Zones Made Real,” reiterates their primary theoretical intervention with Pratt. Linguistic contact zones are “real” in the sense that languages do come into contact with one another, and scholars can use this phenomenon as a lens to better understand literacy. However, as Cushman and Emmons—like Harris and Miller— caution, literacy researchers and instructors should be wary of the pitfalls of using contact zones only as metaphors for cross-cultural encounters.

Though Joseph Harris dubbed Pratt “the patron theorist of composition” for current conversations in the field (161), Pratt neither invented nor is the sole owner of contact zones. “Contact zone” describes a linguistic situation in which different languages interact with and borrow from one another. It is a language-focused and cross-disciplinary concept, which I argue makes it a rich conceptual and methodological framework for literacy studies and perhaps an opportunity for renewed attention by compositionists. It offers an approach to investigating literacy instruction that transcends binaries such as local, global/translocal, oral, and literate. This happens because issues of language diversity, social, political, and historical contexts, and individual agency are just as central to the study of literacy as they are to teaching writing, and a contact zone framework offers a way to view these issues as interrelated. In addition, contact zones facilitate dialogue with other disciplines including composition studies, sociolinguistics, pidgin and creole linguistics, history, literature, comparative studies, and education. Given the productive debate that contact zones have facilitated in composition studies and the linguistic focus that contact zones maintain, studies of literacy in any context can benefit from considering the sets of issues and questions that a contact zone framework would encourage.

Literacy Contact Zones

Set within the contexts of history, language difference, orality, and power differentials, contact zones foreground interaction rather than divides. This emphasis on interaction disrupts some potential misunderstandings of complex literacy situations. This section presents three cases in which attending to the contexts and interactions that a contact zone framework made visible allowed me to pose more nuanced questions about the particular dynamics I was observing. All three cases here involve textual analysis that was a precursor to a larger project I am currently working on in which I use contact zones as an analytical framework for a comparative case study of literacy volunteer preparation in two organizations working in the U.S. South and in Haiti. The first case examines UNESCO’s website and makes visible orality. If literacy is viewed as embedded in contact zones, then much of the language and other cultural circulation takes place in a vibrant oral context. Orality is necessary in linguistic contact zones where languages and cultures are not shared and where pidgin and creole languages emerge from these oral exchanges. The second case points to the major affordance of this framework, as contact zones are by definition the dynamic interaction between the immediate and the wider-ranging uses and meanings of literacy (or the micro and macro scales in Bartlett and Vavrus’s work)4. This example revisits scholarship on a famous Paulo Freire-inspired literacy campaign in Nicaragua. It reminds us that the circulation of literacy must be associated with the ongoing colonizing project when viewed through a contact zone framework. As such, the oral, literate, and ideological practices that are imported must be assessed for their complicity with continued colonization and imperialism. Finally, these immediate and more wide-ranging elements of literacy and orality are not fixed or absolute but rather constantly negotiated, as the third case in Haiti highlights.

UNESCO’s website uses an intriguing combination of immediate and wider-ranging elements of literacy. As an international governmental organization, UNESCO relies on literacy having a “translocal” value in order to make global statements about its necessity. We see the wide-ranging view of literacy clearly in statements such as this: “For individuals, families, and societies alike, [literacy] is an instrument of empowerment to improve one’s health, one’s income, and one’s relationship with the world” (“Literacy”). UNESCO.org also affirms more immediate understandings of literacy in policies: “[a]t the country level, UNESCO encourages the implementation of policies that are relevant to distinctive national contexts, in line with the commitments endorsed by the international community such as the six Education for All goals” (“Literacy: Policy”).This same page offers a bulleted list of different ways of “[p]roviding service while respecting diversity of context,” which include “[l]inking formal and non-formal approaches to education” (“Literacy: Policy”). The immediate contexts of literacy, which are barely visible from the vantage point of UNESCO’s global policy-making, are entirely dependent on the wide-ranging concept UNESCO sets forth that “[l]iteracy is a fundamental human right” (“Literacy”). Though pushing for collaboration with communities and local practices, UNESCO sees literacy as part of the abstract mission for global peace and equality. “Illiteracy,” UNESCO claims, “is an obstacle to a better quality of life, and can even breed exclusion and violence” (“Literacy”).

In spite of the universalizing rhetoric about literacy that UNESCO deploys in its website, viewing the role of immediate and wider-ranging literacy practices through the lens of a contact zone offers additional illumination. Though UNESCO treats literacy as empowering, asking how immediate and wider-ranging literacies will “meet, clash, and grapple with each other . . . in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination” casts a very different light on this mission (Pratt, Imperial 7). In affirming the wide-ranging value of literacy, UNESCO disenfranchises the immediate. It is the wider-ranging view of literacy that UNESCO privileges in setting goals and deciding what to do about the “distinctive national contexts” it encounters: quite an imperial project. Though literacy can contribute to different democratic and gender equality efforts (see Cody; Bartlett), assuming that wide-ranging literacy initiatives can navigate any context and achieve these laudable results leaves little room for local needs and immediate literate and oral practices. Viewing these immediate contexts for literacy as contact zones troubles and exposes the compelling narrative about literacy that UNESCO constructs. A contact zone framework would urge us to consider the negotiations—Pratt’s clashing and grappling. As with colonized groups experiencing unfamiliar languages in a linguistic contact zone, communities who participate in UNESCO literacy initiatives must negotiate wide-ranging values and understandings of literacy, all of which will take place in a dynamic oral environment. UNESCO’s website already leaves room for both immediate and wide-ranging literacies, but without a theoretical model to interrogate the power dynamic between these disparate spaces and literacies, the wide ranging slips into a dominating role. A contact zone framework highlights the interaction of people and interaction within and between components of contexts, such as power and orality. This framework pushes back against fixed views of literacy that often propel literacy campaigns, including UNESCO’s (Arnove and Graff; Street, Literacy). Finally, a contact zone lens foregrounds power dynamics, history, language difference, and orality—all of which are central in creating linguistic contact zones.

In contrast to the international governmental organization, UNESCO, the literacy campaign that accompanied the first year of revolution in Nicaragua appeared to include indigenous languages in its efforts to rapidly increase the national adult literacy rate. Examining the Nicaraguan Literacy Crusade with a contact-zone focus on interactions and contexts reveals additional complications between immediate and wider-circulating beliefs about literacy as well as—once again—asymmetries of power, especially as they relate to language ideologies. Jane Freeland analyzes the Nicaraguan literacy campaign of 1979 and 1980, which was mobilized by the new Sandinista government and inspired by Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Freeland’s article in the International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism calls attention to the rise of the Sandinista government in Nicaragua and its conflicts with the Costeños on the Atlantic Coast. Freeland suggests that scholars do not pay enough attention to the role that language debates played in the Sandinista/Costeño conflict (214). Language became an essential element and even substitute for different ethnicities during this period. With a volatile political backdrop, “linguistic purism” coincided with national support for the anti-Anglo/imperial and pro-Mestizo government, and thus “‘rescuing’ and maintaining language” equated “rescuing and maintaining ‘culture’” (220). The National Literacy Crusade initiated by the Frente Sandinista de Liberación National (FSLN) promoted Freirian conscientization and unity through the national language of Spanish. The united indigenous Costeños, however, demanded bilingual literacy (221), and the Sandinista regime obliged them by designating local groups as leaders of the English language literacy initiative. Costeños were permitted to develop their own exercises based on Freire’s conscientización lessons but were not allowed to generate their own terms or lessons. Though given literacy materials to translate into bilingual English and Spanish lessons, the Creole translators used subtle resistance approaches, such as changing the images accompanying the lesson or using ambiguous terms in English that could support a counter claim of Costeño unity as opposed to the national unity byline of the FSLN.

If the contact zone model enabled a greater understanding of the power dynamics behind UNESCO’s rhetoric, in the Nicaraguan literacy crusade it reminds us that language and literacy practices of the (immediate) disempowered Costeños as well as the incoming (wider-ranging) Sandinista regime are intimately related to negotiations of language ideologies.5 Even Pedagogy of the Oppressed can be used for coercive purposes of erasure when its dialogic ideals are mobilized under the guise of nationalism. The Costeños’ subversive translation of the FSLN’s pedagogical material reads like a description of one of Pratt’s “arts” of the contact zone: “a conquered subject using the conqueror’s language to construct a parodic, oppositional representation of the conqueror’s own speech” (35). As a literacy contact zone, the emphases of history, orality, power, and difference negotiation are just as important in this example as with UNESCO’s website. Freeland discusses the struggle between the Sandinistas and Costeños in terms of power, and a contact zone approach to literacy in this context would also highlight the coercive and counter-hegemonic contentions surrounding literacy. It would be easy to see the National Literacy Crusade as solely concerned with reading and writing. However, underlying the racist, anti-indigenous push for linguistic unity among Nicaraguans is a view of language closely connected to divergent oral and cultural contexts. Freeland points out the slippage between language, ethnicity, and culture that the call for “linguistic purity” encapsulated. A literacy contact zone framework would push us to see the oral (rather than illiterate) linguistic contexts in which such initiatives occur. The intentional double meanings in the pedagogical texts for the Costeños are examples of written and oral transgressions of the dominant discourse and literacy project. These materials are also an example of how such texts and discourses in a contact zone are not either immediate or wide ranging but an ongoing negotiation of both. Though the Costeños are certainly an example of a non-dominant, “grassroots” group of language speakers, this grassroots literacy campaign acts upon them bringing wider-ranging literacies and values about literacy, which they resist with targeted adaptations. A contact zone perspective on this complex situation highlights these tensions.

The literacy organization that I have spent the last four years working with takes college students from the U.S. to Haiti to work with local teachers and communities on collaborative projects. The first project I worked on with this group was to pilot a children’s book initiative with kindergarten through second-grade instructors in central Haiti. The books were intended to provide affordable teaching materials, which are sorely needed throughout much of Haiti, and to specifically support students’ reading in Haitian Creole (or Kreyòl). This final example of an immediate context for literacy contact zones highlights a prolonged contention about language and literacy and is the backdrop for my own research on literacy organizations. The language and literacy situation in Haiti further pushes for greater interrogation of seemingly positive language policies—such as those proposed by UNESCO—amidst complicated historical circumstances. Kreyòl is the language spoken by at least ninety percent of Haiti’s population. However, French maintains its status as the language of power both explicitly in its use in official and administrative documents and through its continued prestige and privilege. Haitian schools teach French literacy alongside Kreyòl beginning in primary school. The complexity of the school language debates is evident when proponents on both sides claim to foster empowerment for speakers of Haitian Creole. Yves Dejean is an outspoken advocate of ridding the school system of French education because Kreyòl is the “native language” and is “spoken by everyone born and raised in Haiti” (204-05). He lists reasons for this stance: that it is not very realistic to implement an effective bilingual education program in Haiti (indeed, this has not proven successful in the past); that Haiti is vastly monolingual in Kreyòl; and that there will still be enough people fluent in French to allow for international communication—this is certainly the case now in spite of under-supported French instruction.6 Alternatively, Valerie Youssef proposes that more effective bilingual instruction is desirable because children are adept at learning languages, two languages are better than one, and Haitians themselves see French as advantageous (188). Are Haitian Creole speakers more “empowered” emphasizing Kreyòl as the language of power and rejecting the French language of their former colonizers? Or are they more empowered by having access to high-quality instruction in both French and Kreyòl? Conversely, is rejecting French as a language of instruction denying Haitian students the ability to acquire a beneficial second language, or is teaching French reinforcing the elitist and even colonial anti-creole language attitudes? In Haiti, literacy’s wide-ranging associations are instantly complicated by a simple question: which literacy?

Here again we can see interrelated literacies and oralities immersed in power dynamics akin to, and even literally amidst, a contact zone. The wide-ranging elements in Haiti are the international French language as well as the abstract value of literacy that fuels academic and nonacademic attention to Haitian literacy. These two wide-ranging components are at odds, however, because of the overwhelming oral, Haitian Creole setting. We can also see from this more immediate context that beliefs about literacy, while dependent on context, still maintain literacy myths. Parents and teachers in Haiti speak of literacy as reducing crime and poverty. As Youssef notes, Haitians want to learn French as well. These are certainly clashes and negotiations between immediate and wide-ranging literacies and oralities, and we must be careful to attend to the specific configurations of power within these dynamics.

Literacy studies scholarship is rich in models and methodologies for investigating literacy. Scholars in composition are also adapting and extending literacy studies concepts, such as Daniel Keller’s case study examination of Brandt’s idea of the “acceleration” of literacy and reading practices among incoming college students. The examples of literacy contact zone analyses I provided focus on historical and rhetorical analysis, but literacy researchers from a variety of disciplines and methodologies, including composition, can benefit from using contact zones as a conceptual framework for examining literacy. Ethnographic, educational, linguistic, sociological, and other social science methodologies also stand to gain from focusing on the contexts that contact zones (and literacy studies scholarship) foreground: history, orality, language difference, and power. Composition studies research extends the view of the contact zone concept into instructional settings, enabling practice as well as analysis through the lens of a contact zone. Even so, compositionists can also reconsider contact zones as a concrete concept that calls attention to the contexts that literacy studies research holds as valuable. Literacy contact zones offer not a new way of viewing literacy but a framework for enacting the rigorous contextualization of literacy that literacy and composition studies encourage. Contact zones offer a much-needed backdrop for literacy studies to consider immediate, wide ranging, and the messy combination of these literacy and oral practices and values. Moving beyond over-distinguishing features such as orality, literacy, local, and global, contact zones enable the complexities and interrelations between these components of literacy to be visible.