Abstract

This article explores how the children of immigrants queried and enacted the immigrant bargain narrative in their orientations to literacy and schooling at an afterschool program in New York City. The Mexican American elementary school students in this study expressed a common “immigrant bargain” narrative, a working-class immigrant family story of parents’ past and present sacrifices redeemed and validated through their children’s future academic merits (Louie 23; Smith 123). Language differences, transnational movements, and family histories affect how the children of immigrants imagine their parents’ migrations and their own transnational identities and literacies. Their identities as students, for example, compelled them to perceive their academic work ethic as repayment for their parents’ sacrifices, doubled with sometimes unreasonably high academic expectations for literacy achievement measured by merit. Literacy mentors and educators unfamiliar with the immigrant bargain should be attuned to its power for autobiographical writing, expressing both what motivates and constrains family migrations and second-generation students in their own academic goals. Afterschool program organizers, youth mentors, and school counselors especially should consider how the narrative builds confianza, or trust, and offers space for encouraging a transnational orientation to literacy in dialogue with immigrant families’ academic motives, goals, and preferences.

Keywords: emergent bilingualism, immigration, translanguaging, translingual literacies

Contents

MANOS, The Mexican American Network of Students

Writing about Opportunity En Confianza: A Translanguaging Event

Introduction

This article draws from six years of longitudinal qualitative research into how emergent bilingualism affected family literacy practices at the Mexican American Network of Students (MANOS) K-12 afterschool program, a grassroots, immigrant community program in New York City.1 Focusing specifically on the writing of three second-generation Mexican American mentees at MANOS, I will describe how the commonalities of the immigrant bargain narrative established these students’ views about goals and the merits of education. The immigrant bargain describes an intergenerational class-based expectation that working-class immigrant parents’ sacrifices be redeemed and validated in the future through their children’s achievements in US schools (Smith 194). The immigrant bargain is a transnational migration narrative that legitimizes language-minoritized, first-generation parents’ high hopes that their children learn English and work hard in school while also exposing second-generation youths to their parents’ immigrant and language minority status in the US mainstream. When understood with empathy and genuine respect for rich and strong family values, the power of the storyline can potentially prompt educators to organize literacy assignments seeking autobiographical and community “funds of knowledge” while aligning potentially diverging academic aspirations among immigrant families (González, Moll, and Amanti 277).

Language differences, histories, and family lives impacted how MANOS mentees perceived their life circumstances in New York City in relation to their parents’ circumstances in Mexico. Marisol, Nansi, and David, the three MANOS mentees of focus in this article, shaped their understanding of migration and transnational identities in relation to education in Mexico and in the United States, but for their literacy practices, their dual range of perspectives did not decrease all constraints. Immigrants develop a dual frame of reference, or “bifocality,” in which they “constantly compare their situation in the ‘home’ society to their situation in the ‘host’ society abroad” (Vertovec 974). Through immigrant bargain sacrifice narratives, second-generation youth both identify with how hard life can be for their parents while also comparing their own struggles to that of their parents (Kasinitz, Mollenkopf, Waters, and Holdaway 21). The immigrant bargain and the promise of the self-actualized American dream understood as upward mobility within a meritocracy both predicate an intense work ethic with promises for future success. MANOS parents tactically employed the immigrant bargain to reaffirm their authority in educational matters for their children, promoting family involvement in this way. Literacy researchers, mentors, and educators unversed in the immigrant bargain’s power for probing the bifocality implicit in the narrative must recognize how the intergenerational story both motivates and constrains students to establish attitudes and goals toward US schooling as they envision their families’ transnational trajectories.

The diversity of perspectives and literacy uses associated with immigrant bargain is impossible to capture in a single writing event. For instance, the immigrant bargain is completely different for 1.5-generation students, those born abroad but raised in the United States who share characteristics of both first and second generation (Harklau, Losey, and Siegal 4). Nevertheless, this sample of three MANOS students gives qualitative detail to local literacy practices with transnational frames of reference. Ethnographic research into literacies of transnational communities contributes to theories of localizing intergenerational situated activities and practices among communities negotiating textual agency across languages, ideologies, institutions, and nations.

Literacy researchers must challenge the individualizing trap of meritocracy. Assessed through examination or achievement, meritocracy is a system of individual advancement through structure. The individualist rhetoric of meritocracy combats all notions of literacy as a social practice for community building and instead affirms an all-out competition where rivals allegedly have an equal opportunity to literacy and upward mobility. A critical literacy approach opens literacy events to reading the gaming of merit, making explicit the structured inequalities of the meritocratic system while also challenging dominant literacies and the status quo.

The immigrant bargain is a story about what motivates students, about the stories of family and sacrifice. When implicit messages about the immigrant bargain become miscommunicated in families, however, meeting parents’ expectations can create aspirational pressures for children. Afterschool mentorship, though, offers one way of realistically aligning the trajectories of parents and children while brokering communication between generational, linguistic, and cultural differences, and what echándole ganas (moving forward) in an individualist meritocracy means among communities. My contention in this article is that writing about the immigrant bargainbuilds dialogues of intergenerational confidence, of confianza, for community building and local literacy engagement by recognizing the dignities of students’ “hybrid” literacy repertoires and identities (Bartlett and García 50). As a community fund of knowledge, confianza “provide[s] children with contexts for learning that are dynamic and built around multifaceted relationships” (Monzo and Rueda 74). For literacy teachers, a culturally sustaining pedagogy engaging these storytelling practices could potentially reshape how we think about writing assignments that involve and sustain immigrant family histories and literacy narratives, increasing access to collaboration and meaningful involvement with homework or enacting agency in the making of the family story. These migration narratives support intergenerational bonds between children and elders because the stories of adult sacrifice involve helping the young.

As the writing produced by three MANOS elementary school students demonstrates, literacy projects that explore students’ abilities, aspirations, imaginations, and community social consciousness are culturally relevant for transnational communities. The projects by MANOS mentees scrutinized New York City’s connections to Mexico, and Mexico’s to New York City, reflecting on values about education in both nations. Afterschool and family literacy program organizers, youth mentors, and school counselors especially should consider how the transnational immigrant bargain offers a space for intergenerational dialogue with immigrant parents about forming academic motives and goals with rather than for children, even despite the monolingualized, academic power of English.

MANOS, The Mexican American Network of Students

The informants in this article participated in a larger six-year ethnographic research project at MANOS. The three students were among the 22 participating MANOS mentees, in addition to 11 volunteer mentors and 10 parents of Mexican-origin at the MANOS community-mentoring program in New York City.2 MANOS offered evening afterschool homework tutoring services six hours each week free of charge. MANOS was located in the damp basement of a Catholic church in one of the city’s outer boroughs. For ten years, the grassroots program mediated between local Mexican immigrant families and the larger Mexican community in New York City, as well as between families and local institutions, primarily New York City public and charter schools. MANOS operated as a safe space for immigrant parents to discourse with one another about school policies and experiences, as well as to participate in their children’s educations openly in their home language. MANOS mentors not only aided mentees with homework in English and Spanish, but also simultaneously helped parents navigate the educational system, offering bilingual “institutional networks of support” for immigrant families (Louie 161), subsequently moderating stresses on parent-child relations and facilitating parental involvement in children’s educational endeavors.

Research data for the entire project consisted of the following: digitally recaptured images of texts produced by MANOS mentees, parents, and mentors; photographs; and transcripts from semi-structured and structured in-person and written interviews. Over the course of six years of research at MANOS, I collected over 3,000 pages of field notes and interview transcripts, 85 minutes of video footage, 160 hours of audio recordings, 500 photographs, and 300 photocopies of student homework.3 I categorized transcribed interview and homework sessions, field notes, and essay and creative writing assignments as texts. I categorized photographs and homework copies as artifacts. From the families, I also requested and collected as many pieces of writing as possible, treating these as literacy artifacts in order to examine both the varied occasions for formal and informal literacy practices in the families and the different genres represented. With certain pieces of writing, I conducted group interviews with participants involved in compositions about their recollections of the events surrounding the makings of specific texts. I categorized video and audio data according to situated moments of literacy practices. I digitally recorded homework tutorials involving mentors, parents, and children. From each of these categories of artifacts and media, I triangulated interviews and texts and analyzed them according to narrative units I defined as “translanguaging events” (Alvarez 327), bilingual communicative situations involving communication about a text in practice. Translanguaging events are narratives that represent emergent bilinguals engaging their bilingual repertoires in social situations. Such moments of translanguaging occur as dynamic bilingual enactments of translanguaging in shared situated contexts for literacy in communities (García 119). Translanguaging events are illustrative of the potential to “read” situations as narratives for theorizing literacy practices. The translanguaging event later in this article shows students creatively and critically strategizing articulations of the immigrant bargain.

The theme of the immigrant bargain became more present during translanguaging events as I noticed elements of it reported to me by youth during homework sessions. For this reason, I decided to investigate how the immigrant bargain affected youth and parents at MANOS. The single translanguaging event I focus on in this article illustrates students writing about the immigrant bargain while also articulating transnational social inequalities. Responding to a photograph of students at a poorly funded school in Mexico, MANOS students compared education and opportunity there with the United States, while exploring their own situations and experiences with social inequality in New York City.

Confidence and Community

A wealth of mentorship research (Hirsch, Hedges, Stawicki, and Mekinda; Rhodes; Rhodes and Lowe; Suárez-Orozco, Suárez-Orozco, and Todorova; Smith) argues that dedicated commitment between non-familial adults and youth can have positive impacts on the academic outcomes of children and adolescents, especially in low-income urban areas. MANOS mentors helped bridge relationships between the local Mexican families and the traditional, English-dominant schools, despite existing without any direct connection to any school. MANOS brokered several connections, first among the ethnic enclave and next with mentors from around the city, all geared toward maximizing the potential for the contact both in time and commitment. Time and commitment were what truly created a sense of validation and support, but also confianza, a sense of trust, of confidence resulting in the ease of two-way discussionsabout schools and the community (Zentella, Building 179). Confianza was the social glue that maintained the integrity of the MANOS program and was indeed validated in the friendships forged between MANOS mentors and families. A bond of confianza on MANOS’s part meant that informed parents were a requisite for educational success—the better informed the parents were, the more likely they were to become further involved in establishing consistent educational expectations with their children and sharing mentorship.

My inquiries about why Mexican-origin students in New York City weren’t achieving as highly as their immigrant classmates began with examining the systems of merit and assessment, then finding potential points of intersection between school and family behavior codes. The system of meritorious work ethic, I realized, mirrored similar ethical arguments in the immigrant bargain narrative among MANOS families. MANOS parents, children, and mentors brokered and negotiated the immigrant bargain as opportunity narratives between families and in the community, which sometimes required thinking about merit from a larger perspective.

As a researcher witnessing the bilingual aptitude and eagerness for learning in the MANOS community, I questioned popular local accounts about what supposed educational achievement gaps for Mexican-origin youth in New York City really measured. According to Kurt Semple’s 2011 New York Times article “In New York, Mexicans Lag in Education,” two-fifths of Mexican students in New York City would not graduate high school and only one in twenty would pursue college educations. Compared to New York City’s major immigrant groups, Mexicans seemed to be faring the worst educationally as “41 percent of all Mexicans between ages 16 and 19 in the city have dropped out of school.” Semple argues the roots of the problem are undocumented immigration status and lack of parental involvement. He writes, “Many Mexicans are poor and in the country illegally. Parents, many of them uneducated, often work in multiple jobs, leaving little time for involvement in their children’s education.”

Semple’s statistics are compelling, but his rhetoric is demeaning and also misguided. The dropout statistic, unfortunately, is actually higher. Semple also doesn’t account for differences between Mexican-origin and Mexican American students in New York City. Sadly, according to New York City Census data analyzed by the Center for Latin American, Caribbean, and Latino Studies Latino Data Project, 48.6% of Mexican-origin people age 25 or older did not graduate high school in 2010 (Bergad 39). These 2010 numbers further aggregated, however, reveal that 15% of US-born students of Mexican origin do not graduate high school (40)—a staggering 33% achievement difference between Mexican immigrant and Mexican American youth.

Children born in the United States to immigrant parents fared significantly better than newcomer students; however, Semple’s article lumps both groups together. The numbers themselves are a bit misleading, since presumably the first generation would have had partial education in Mexico or perhaps would not have interacted with US schools. Nevertheless, the low high school completion rates of newcomer Mexican immigrant youth are deeply troubling on their own. Semple’s rhetoric about parents’ involvement clearly becomes his focus for blame, reinforcing the meritocracy paradigm, placing blame in the wrong place and evoking a dangerous stereotype of inept parenting. As the immigrant bargain narrative proves, attrition is not a cultural or familial problem but is due to more systemic social constraints such as racism, poverty, and irregular legal status.

Semple, like too many others, blames parents for student performance, and also for migration, without recognizing that the playing field was not equal for Mexican immigrants of all ages, parents and children, and that within families parental involvement is not the problem. The immigrant bargain naturally played out in all families, but within the Mexican communities, the immigrant bargain’s pressures for upward social mobility drew on the parental sacrifice and work ethic. This of course was where the need for MANOS mentors in the community became important: to mentor potential disconnects in Mexican families, by aligning narratives and offering access to resources for educational opportunities and shared community strengths.

Without a doubt, immigrant families face educational predicaments, largely stemming from the negotiations between home minority languages and that of the dominant institutional language. The support and cultivation of English literacy through the MANOS program emphasized the community’s efforts to engage with the dominant institutional language while maintaining the integrity of the language they used to communicate in personal relations. One element that was shared across all the MANOS community’s stories of migration and individual educational travails was a common narrative of family survival and perseverance. In English and Spanish, MANOS students were familiar with these tales. The compositions of MANOS mentees Marisol, Nansi, and David demonstrated that familiarity and illustrated how social class and language were deeply intertwined. The translanguaging event and its resultant texts vividly illustrated how these MANOS mentees voiced the immigrant bargain and a schooling orientation favorable to making their parents proud. Within the city’s Mexican communities, the immigrant bargain’s pressures for superación, upward social mobility, found few models from which to draw (Gálvez22). This was of course where the need for sponsoring mentors in the community became an important resource to rectify disconnects in Mexican families, by aligning experience with superación aspirations and offering trust as resources for educational mentorship communities.

Thirty-three-year-old María and her four children had been members of MANOS for two years. The family had moved to the east coast six years before, after living near her sister’s family in California for ten years. María’s younger brother lived in a Little Mexico barrio in New York City and he convinced her that work opportunities and treatment of immigrants were better in New York than California. She was born in a rural area of Morelos, Mexico, which she noted was the reason why she had only two years of formal schooling. Her father died when she was young, and her mother supported María and her six siblings as a migrant farm worker throughout the central and northern Mexican countryside, following harvest seasons. María noted that she and her siblings also worked to contribute to the family income. She immigrated to the United States when she was sixteen years old. She worked cleaning offices and apartments in Manhattan.

María’s first language was Mixtec, an indigenous language to Mexico. She learned to speak Spanish in Mexico growing up, but Mixtec was the language of her small home community in Morelos. During her twenties, she learned to read and write Spanish in California where she simultaneously had been learning more spoken and written English. Her children were soccer enthusiasts, and her daughter Gina demonstrated a remarkable commitment to helping her mother. Gina always translated bills, report cards, and, generally speaking, anything written in English deemed important. “Because I have to help her, because for some of the stuff in English she don’t have anyone to help her. And she helps me too,” Gina said during an interview.

María mentioned to me that she wished she would have had the opportunity to go to school like her children, but she had to work at an early age to help support her widowed mother. As a child, her family lived as migrant farm workers in Mexico for several years, before María and her sister and brother migrated to the United States. She recounted, with tears in her eyes in front of all her children during an interview that “mis propios paisanos se burlan de mí por el simple hecho de no saber escribir mi nombre, pero yo nunca tuve la oportunidad de ir a la escuela, y solamente hablo un dialecto” (My own Mexican people look down on me for the simple fact that I don’t know how to write my own name, but I never had the opportunity to go to school, and I speak only a dialect). The dialecto she described was her home language Mixtec.

For María, it seemed natural that she would experience discrimination against her Mixtec roots abroad, but it made no sense to her to receive similar treatment from Mexicans experiencing similar discrimination from the United States mainstream. Mixtec speakers face structural racism in the linguistic market of Spanish in Mexico and the United States, and this was one reason why she referred to her language as a dialect. Her family’s economic conditions limited opportunities to study, despite her intense desire to attend school. Her children—also in tears—had heard this story before. All were mindful of the hardships their mother lived through as a girl, her educational history, and the social and language challenges she still faced in New York. María’s children, like most MANOS mentees, were sensitive to the narratives of their parents’ educational hardships. They also understood that their parents rhetorically used their personal history narratives in order to teach their children important lessons about living responsibly and studying hard. Parents used the immigrant bargain to teach their children about the difficulties of life and migration and as a means to pressure them. The pressure was certainly effective, as the tears in the room proved.

The MANOS parents by and large all subscribed to the immigrant dream of upward mobility for their children, as sponsored through educational success and persistence. Immigrant parents attempted to strike compromises for responsibly maintaining their children’s high motivation for their schoolwork, persuading their children to take their studies seriously by invoking the immigrant bargain. According to Robert C. Smith, such a bargain occurs in most families—immigrant and nonimmigrant alike—but for immigrant families, the “life-defining sacrifices of migration convert it into an urgent tale of moral worth or failure” (126). The second-generation successes justify the first-generation’s sacrifices, but failures produce a “burden of shame” in family economies of “moral worth.” Smith claims, “children understand the implication that their parents, who overcame long odds, would have done better, and they judge themselves harshly” (126). The potential for shame, as Smith argues here, stems from children comparing themselves to their parents and not meeting their expectations or, alternatively, for not valuing their parents’ struggles and being sinvergüenzas, or shameless.

Vergüenza, or shame—being either with or without shame—organizes intergenerational power dynamics in Mexican and Mexican American families, maintaining conservative patriarchal relations of belonging (Díaz-Barriga 258). The power dynamics of vergüenza for immigrant families, however, speaks to a family struggle and group work ethic, and the sinvergüenzas are those who don’t pull their weight. The pathos of the immigrant bargain and its rhetoric of vergüenza obliged MANOS mentees to value hard work, to “grow up” and affect (even temporarily) a certain level of emotional and intellectual maturity while being mindful of their parents (Orellana 21). Yet for MANOS families, the immigrant bargain did not disempower parents or restructure family relations. MANOS parents still retained power in their families, even in the midst of competing English discourses that sometimes undermined their authority. Rather, MANOS parents tactically employed their migration narratives to empower their children and to legitimize their expectations that they work hard in school. The MANOS parents’ messages about vergüenza and education rang loud and clear, and for the MANOS mentees the stories moralized a family-oriented work ethic.

As with any message, however, the immigrant bargain may be interpreted differently than intended and is dynamically impacted by power structures. Though first-generation parents use the rhetoric of the immigrant bargain to motivate their children, some immigrant youth interpret the immigrant bargain as confirmation that, in order to be successful, they must not be like their parents, and they experience a pressure for assimilation and mobility that encourages them to dis-identify with their parents and their families (Portes and Rumbaut 113). As noted in Semple’s Times article, the public realm further encourages dis-identification with parents as reactive youths note the public’s perceptions of their parents as immigrants. Second-generation youths who ascribe to these nativist perceptions choose to differentiate their ethnic identities away from their parents and see themselves as parts of mainstream society, abandoning the strengths of their families. The strengths of intergenerational learning can promote academic motivation and translanguaging literacies that connect to the real practices and contexts of students navigating the immigrant bargain.

Writing about Opportunity En Confianza: A Translanguaging Event

All the MANOS parents surveyed in this study had faced life struggles their children had yet to completely fathom but which their children had glimpsed in family narratives. As they aged, children became more familiar with the stories of their parents’ migrations from Mexico. At early ages, nearly all MANOS mentees could offer accounts of their parents’ lives in Mexico, their difficult migrations, and their economic hardships in the United States. These migration narratives of the parents supported an intergenerational bond between children and elders because the stories of adult sacrifice involved helping the young. MANOS mentees appreciated the sacrifices the migrating generation had performed in order for the next to gain a better footing in the United States, and, subsequently, in life.

Several of the MANOS mentees had traveled to Mexico to spend time with family during school vacation months. All the parents in this study hailed from small towns on the outskirts of larger cities and maintained connections there. During summer months, it was not uncommon for some MANOS youth to visit for several weeks. For these youth who traveled to Mexico, the contrasts between what they identified as rural homeland and urban New York City were compelling: “New York is crowded, and over there isn’t a lot of people next to each other. And then Mexico there’s animals like donkeys. And it’s very, very hot,” said 11-year-old Luis about his parents’ village in the Mexican state of Puebla. Teenager Sara said of her parents’ village further west in Puebla that “there’s a lot more poor communities. And I feel like we live in a better situation than they do, and it’s sometimes—like—wow, you really don’t see that a lot. The Mexicans over there think that we’re lucky we live in a big city, that we have lots of opportunities, and that we have nicer clothes.”

When speaking of Mexico, whether having been there or not, MANOS mentees constantly emphasized its social conditions, especially what they deemed as its poverty in relation to the United States. Whether having first-hand experience with life in Mexico or not, however, the MANOS youth all internalized a comparative transnational framework for understanding the social relations between Mexico and the United States, even to the differences between clothes and wealth. They also became aware of how these relations played as the backdrops in ongoing family narratives of migration and their social class positions within the American mainstream. The “third-world” poverty in Mexico, compared to the urban poverty in el norte (the north), New York City, led MANOS parents to juxtapose their lives’ stories with their children’s, rhetorically embedding children into their transnational family narratives of superación. MANOS mentees sometimes subscribed to these narratives, regarding themselves as individual links in immigrant family chains of class progress, and sometimes questioned them. Social aspirations encoded into these stories moralized their parents’ obstacles as sacrifices for better lives for future generations, but aspirations also compelled them to bargain their positions in families and their work ethics. For students, thinking and writing about such bargains involved in these familial sacrifice narratives parse how second-generation students consider how difficult life could be for immigrants while also opening spaces for building trust and opening dialogues with students and communities.

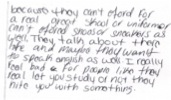

In order to practice their writing, Carlos, MANOS’s program director, invited a group of three MANOS elementary mentees, born in the US to immigrant parents to respond to an image from the Spanish language newspaper El Diario de México (24 Oct. 2008) about children at school in Veracruz, Mexico (see Figure 1). There was no accompanying article for the image. The caption emphasizes the hope of children in Xalapa despite what appears to be minimal institutional support. Judging by the handwritten English caption added by Carlos, the image and text either communicate a sense of hope amid suffering or project a sense of thankfulness for schooling in the United States.

Figure 1: MANOS mentees responding to image of Mexican school.

Carlos read El Diario every day on his commute to MANOS from his day job, and he sometimes contributed articles about his activism for the newspaper. When he saw the image, he said it reminded him of schools in rural Mexico he attended before emigrating from rural Puebla, and he wanted MANOS students to see students like themselves in different conditions, an intentional and explicit appeal to the immigrant bargain rhetoric of superación narratives. He cut out the photo, pasted it on a piece of paper with the message “A Role Model School” above the image, and added a subtext below it asking for “Reflections,” with the question, “What would you do to become a better student?”

Carlos maintained the original caption printed by the newspaper on his improvised assignment. The caption for the photo reads:

Sentados en el piso a sobre ladrillos, los alumnos de esta escuela en Xalapa, Veracruz, estudian la primaria, sin importar las incomodidades, pues su deseo de superación es mayor. Tampoco hay pizarrón, pero sí una maestra que imparte los conocimientos. Estos estudiantes son ejemplares, asegura la profesora.

Sitting on the brick floor, the students at this school in Xalapa, Veracruz study, not minding the uncomfortable conditions because their desire for achievement is greater. They don’t have a chalkboard, but they do have a teacher to impart knowledge. These students are exemplary, assures the teacher.

Carlos made photocopies and distributed them to the students at MANOS one evening while they worked on their homework. He interrupted different homework sessions as he distributed the photocopies.

“What would you do?” he said to the groups of mentees, parents, and mentors.

The image produced intense reactions from everyone, but since homework was the priority, Carlos told them to keep their photocopies, and people who wanted to talk about the image could do so in a group discussion after they finished their assignments.

Since I had finished tutoring a younger mentee with her homework, I volunteered to organize the response group. With what Carlos had produced, I envisioned a writing activity. I gathered writing materials when Carlos approached with three MANOS mentees.

“¡Ya vámonos!” he said.

I led the group of three mentees to a circle of desks in a corner to work on writing about the image and its text. I knew the students well, fifth grader Marisol, age 11, and fourth graders Nansi and David, ages 10 and 9. They had been taking part in my larger MANOS study.

When the group of MANOS mentees thought about how to respond to the image of students in Xalapa, they weren’t exactly sure what to write about. We read the text in Spanish together aloud, and we collaborated on a translation with quick negotiation, as it seemed the students had fewer questions about vocabulary than about the location Xalapa. They also asked if they had to answer the question that Carlos wrote as a caption. As I didn’t want to limit students to that question, I told them to write and just let the picture tell them what to write. Looking at the photocopy again, I realized that the question was in English, and the caption in Spanish. I realized the question implied an English response. I realized I had to add a caveat about bilingualism.

“In English or Spanish, use both or either one to answer it.”

My “both or either one” was indicative of my open orientation to the informal assignment recognizing the confianza of the space and moment for translanguaging, for using all the available tactics in the students’ bilingual repertoires. Mentees collectively interpreted an image from a Spanish-language periodical portraying the educational conditions of poverty among a group of smiling students squatting on the brick floor of their classroom in an alternative space. The MANOS mentees were free to answer the question en confianza, meaning in the formthey found most suitable for the situation. This of course included and encouraged language mixtures and creations that were part of their everyday literacy practices.

Nansi asked if she had to write an essay.

Marisol and David groaned.

I told all the three mentees they could write how they wanted, but just to write their ideas about the image, and write it as nicely or as badly as they wanted; en confianza, it was only practice. The only catch, I told them, was that they would have to read what they wrote aloud.

“In English?” asked David.

“English or Spanish,” I said. “Inglés o español.”

“Vamos a leerlo después de terminarlo” (We will read it after we finish it), said Marisol.

The following figures were the results produced by the students and which they read aloud after writing for approximately twelve minutes (MANOS was soon closing that evening, and we needed time to hear each version). Nearly all of the students wrote personal responses to the image that delved into the rhetoric of the immigrant bargain, narratives of family superación, and differences in educational opportunities in Mexico and the United States. The juxtapositions of Mexico and the United States illustrated and reaffirmed the bifocality of reference for these MANOS mentees.

Figure 2 is the first text from MANOS mentee Marisol. The transcription to Marisol’s response in Figure 2 reads:

This picture affects me by getting educated the right way. I am glad that I go to a good school. If I was rich or had money I would change everything. I would bring chairs and tables books and a lot of supplies so they get educated more. There happy that they getting educated because some people don’t get educated. I feel like we got opportunities because we’re in the USA, and we don’t care about school and the kids in the picture are happy and there sitting on the floor getting educated. Ellos les estan echando ganas y nosotros si estamos ahi no le echamos ganas. (They are making the effort and if we were there we wouldn’t make the effort.)

Figure 2: Response to Figure 1, composed by Marisol.

Marisol wrote that “I feel like we got opportunities because we’re in the USA, and we don’t care about school,” making a forthright comparison between the youth in the photo and youth in the United States. For her, the youth in the photo seemed happy with their meager schooling conditions. She reverted to Spanish to further clarify and summarize her point: “Ellos les estan echando ganas y nosotros si estamos ahi no le echamos ganas” (They are making the effort and if we were there we wouldn’t make the effort). The comparison between “there” and “here” and the resources that provoked a sense of appreciation for what one had was another common hallmark of how the immigrant bargain was legitimated by parents to their children, and how it figured in social class dynamics in conjunction with nation status. Her final sentence in Spanish more or less summed up the idea that “we”—those born here—don’t appreciate what we have, and we should work harder, like these students who have little. This was the message of many MANOS parents. Her audience in Spanish would get the overall point of what she had interpreted in more detailed English: class comforts deaden one’s sense of appreciation for privilege. Though the public school she attended in the neighborhood was in no sense one of the best schools in New York City, Marisol felt she couldn’t complain when examining the school in Xalapa from the image.

“If they came to MANOS, they would be happy, too,” she said. “Because here we have desks too and teachers to help us.”

MANOS mentees often referred to homework mentors as “teachers,” and here was one instance when Marisol saw their pedagogical assistance as institution-like, at least with what she recognized as a lack of infrastructure with the Xalapa school. What struck me about Marisol’s text was the use of Spanish as coda at the end of her writing. At the end of her text, she code-switched (Zentella, Growing Up 41, 81), producing a translingual text which is something she wouldn’t be encouraged to do in standardized essay examinations at school. Marisol clearly took bilingual liberties because of her awareness of audience for this composition. Her call to action voices a rallying cry within the immigrant bargain rhetoric, envoicing the words of parents arguing for recognizing privilege and repaying their gratitude through hard work and vergüenza. In her coda, she ends the last phrase with the first-person plural nosotros, transitioning from the first-person singular “I” throughout the text. In Marisol’s last phrase, she pinpoints her authority to speak as expert in this negotiation because it’s something she has lived. Through her sense of authority in writing on the subject of the immigrant bargain and her authority to effectively communicate bilingually with her audience, Marisol enacts meaning as she maximizes the interaction with her full translanguaging repertoire both on the page and in her performance.

When Marisol arrived at the last sentence of her composition and her use of Spanish, Nansi asked for clarification as to whether what she just read was a translation or written. Marisol showed Nansi her written text, and Nansi was impressed that Marisol knew how to write Spanish so well.

After Marisol, the group moved to MANOS mentee David, age 9. Figure 3 is the text he composed. The partially damaged text reads:

They are happy because they are learning somting and they want to be somting on ther life and i feel like if i was the president i will send mony to Mexico so tha they could buy tables and chair and books so the kids could learn somting on there life. I think some kids don’t have the mony to buy clothes and feel sad that in New York they have olat of things and they think that got every fucking money in the world and i hate when they are making fun of other kids that don’t hafe money [damaged portion of page missing].

Figure 3: Text responding to Figure 1, composed by David.

Fourth-grader David’s response drew some linguistic controversy to the study group. David’s composition provoked the greatest response from his audience because of his use of the swearword “fuck.” He first read his response in English, watching to see how I would react when he arrived at the expletive. Four additional sets of eyes did the same after he said it. I nodded and asked him to continue. He did so. David’s language choices—particularly marked language choices—expressed a certain kind of force or ownership of the narrative, and I didn’t want to censor that. I knew David, and he was not a student prone to swear in front of me.

After he finished it in English, David read it over and translated sentence-by-sentence into Spanish, with some help from Marisol and Nansi. When he translated his composition, he didn’t use a Spanish equivalent for “fuck.” He used the English expletive, because the emphasis was the same for him in either language. Marisol and Nansi laughed as he said it and immediately looked to see how I would respond again, perhaps in disbelief that I didn’t censor David. I wanted to learn from him, and I didn’t want to waste an opportunity for our group to engage his text.

As for the swear word, I let the mentees know that I understood that word was used around them and that they would use that word amongst themselves. They also had to understand, though, that using it at the improper time could be offensive to audiences.

David nodded and said, “But I get mad about this stuff.” He justified his use as natural during the informal stage of writing, but also as an emotional response to the content of his composition.

I assured the MANOS mentees I wasn’t going to get anyone in trouble and I would permit the word in this composition because it wasn’t a school assignment. For school, this would not be permissible, I said.

“Well, I know that,” David said.

The use of “fuck” in David’s composition effectively utilized the informality of the writing exercise. And as a rhetorical move, he complemented it with the pathos of arguments behind the severe class antagonisms found most distasteful in the social relations between the wealthy and poor in the United States. Again, he offered a solution to the issue when he hypothetically positioned himself as a politician or an individual endowed with the institutional power to make social changes. But when David reached the point of class antagonism, just like with Marisol, the final sentence resonated with a burst of pathos: of a young person who couldn’t stand to witness social inequalities between two people who were—by all measures—equal. David chose to use New York City as one example of wealth and he contrasted this with what he saw in the image. To take this informal writing an additional step further—again beyond the informal and the impromptu—I would have encouraged David to use his writing to question why real politicians allowed such schools to exist for poor children.

When David finished reading his composition and after he demonstrated the freedom in the informality of the assignment by finding room to swear with impunity, he aired his grievance a bit further when I asked what rich students he was referring to.

“The ones that have a lot of things. They show off and make kids feel bad.”

“They bring nice cell phones to school,” Marisol said.

Cell phones and clothing signified wealth and status among the MANOS mentees at their schools around the neighborhood, as they did with MANOS students who travelled abroad to Mexico. Though expensive electronics were not permitted at any of their schools, the mentees reported that students brought them to school anyway, mostly to show, especially just off school grounds before and after school.

David explained that he had recently seen a few older students bullying his classmates outside his school. The image touched a nerve. I asked if he thought students at that school in Mexico also had their own ways of bullying.

“No, I don’t think so because they don’t have books or paper.”

Social status was only operational in the United States then, or in ways particularly identifiable and salient through the semiotics of consumer goods like cell phones or name-brand clothes and shoes owned by some and not by others. Poverty was an equalizer in this sense, but it must be remembered that a photo juxtaposing one of the elite educational classrooms of a private school in the Lomas de Chapultepec neighborhood of Mexico City would have possibly reframed things in an interesting way for the mentees. Within the contexts of their schools, MANOS students didn’t report feeling significantly poorer than their peers, but they knew their families were not as wealthy as some of their classmates’ families.

The group appreciated David’s efforts and we each thanked him for sharing his honesty and using the writing as an opportunity to express his frustrations. Bullying and class differences were something the MANOS mentees identified with and sometimes experienced.

Fourth-grader Nansi Montez composed the text in Figure 4. The partially damaged transcript reads:

That they wish they could have tables and then that they wish that they could have a school to learn or to have better grade or notebook as well. The studonts wish they could have a school like we go on right know. The kids are laugh and sitting on the floor and it might be cold and they are happy to be on skool and than like some people go tosit on the floor like if there poor and can oford a better skool that thats where imagration is and how they real want to change. If I was a govermant of Mexico and I would put tables chairs more teachers so they could learn more about reading, math, science, and computer as well. How [damaged portion of page missing] because they can’t oford for a real great skool or uniform or can’t afored shoos or sneakers as well. They talk about there life and maybe they want to speak english as well. I really feel bad for people like they let you study or not they hite you with something.

Figure 4: Text responding to Figure 1, composed by Nansi.

Like her MANOS fellow mentees, fourth grader Nansi’s text entertained the idea of social change and also how redistribution of resources for schools should be more equitable. She had a vision for what school for the youth in the photo should or could be like, and how she would contribute if she were able to first succeed herself. She also turned the tables on the governments that allowed youth to attend schools in such decrepit conditions. That was something the caption of the actual photo didn’t question. That caption pointed to the heroism of the Mexican youth to suffer and strive to move ahead (deseo de superación) despite constraints. Nansi didn’t look to the victims; she instead looked to causes and she looked to institutions. She also said the students in Xalapa wished they were in the positions of students in the United States receiving an education with more resources. Turning toward the immigrant bargain, we can see the logic at work where those Mexicans living in poverty worked harder than those who live comparatively wealthier. This view led to either a sense of debt to be paid for parents’ sacrifices or a re-evaluation of one’s work ethic in a comparative framework. Nansi points to the image of Xalapa as reason to leave Mexico, as the site “where imagration is” and the motivations for immigrants for opportunity and the dignity of “change.”

After Nansi read her composition, Marisol began a round of applause, followed by David, Nansi, and myself. I asked why she had started clapping and had cheered the rest of us on.

“Because she was the last one, and we all said good things.”

I had to agree. I think Marisol wanted to show support for her friend whom she noticed was a little nervous reading to the group.

I asked Nansi why she thought the children would want to learn English.

“So they could get good jobs and go to college and make their parents happy,” she said.

I reminded her that the children in the photo were in Mexico.

“But in Mexico you have to know English too, my dad and my uncle told me that.”

She confirmed this with David,who was nodding.

“Sí, claro, mejor” (yes, of course, it’s better), he said. He added that being bilingüe (bilingual) was an asset there. According to the mentees, between Mexico and the United States, bilingual speakers of English and Spanish had linguistic capital in each direction, but English, especially its connections to the dominant institutional character of the United States, had more value across borders.

The compositions from the group of MANOS mentees broke down the dual-frame of reference that immigrant youth imagined as class differences between Mexico and the United States. In all instances of the texts produced, these mentees’ projections of poverty in the rural areas mixed with projections of advantage through the markers of US-style schooling. For each of the distinct compositions of the MANOS mentees, the image first called attention to the immigrant ethic that was appreciative for the opportunities available in the United States, in comparison to the limited opportunities of Mexico. Secondly, however, they also pinpointed fundamental social class inequalities that contributed to their own interpretations of meritocracy and living the immigrant bargain’s pressures for superación. The image of school poverty in Xalapa, however, displaces attention from larger social inequities that permit such poverty to exist at all levels of public schooling across the globe. For some of the MANOS parents, the image in the photograph from El Diario is closer to what they experienced in terms of their access to schooling in Mexico. The superación narrative drove many of them to migrate to New York City, and these stories formed the bases of aspirational goals, narratives for echándole ganas, for children and future generations. Echando ganas was the phrase used by Marisol in her composition, and I found that synonym also common to the vocabulary of the transnational immigrant bargain from both parents and children.

Literacy and Mentorship

There were a few mentors at different points during MANOS’s history who criticized the literacy engagement at MANOS as nothing more than tutoring focused on schoolwork. These mentors envisioned a more sustained engagement outside of school without school necessarily being the subject, or at least not the primary subject. The line for them between tutoring and mentoring was firmly distinguished. Yet, these volunteers admitted that it was of crucial importance to help with schoolwork, so they therefore began to blur the line between tutors and mentors. Homework literacy was the common need among families involved at MANOS, and this was what really brought neighborhood parents together in a shared community venture aimed at securing academic support and mentoring. The unique institutional affordances of a grassroots community afterschool program and the potential for mentorship through dialogues and writing about the immigrant bargain narrative complement each other and support students.

Families were thankful to mentors, and mentors were validated by what they saw as a family struggle toward something greater, echándole ganas. Twenty-eight-year-old MANOS mentor Cristina identified with the struggles of immigrant parents and saw them as her own, so she was glad to help out by sharing the experiences she had growing up in similar circumstances as the MANOS families, who were struggling to make ends meet in one of the most expensive cities in the world. She added that the MANOS families were active in their critiques of how MANOS functioned, or that they had a “say” in how things ran. MANOS of course invited parent critique, in order to—as Cristina said—identify the “real needs of the community we serve.” The shared interactions within the community not only opened discussion about educational possibilities and how to navigate schools and afterschool programs, but also on how to take steps toward academic achievement and college attendance.

The educational expectations of immigrant parents and children could be brought into alignment with assistance from trusted mentors. Most MANOS mentors were first-generation college students with sustained involvement with the community who were familiar with its rhetoric of the immigrant bargain. Like MANOS parents, mentors also emphasized the obstacles they faced on the road to college, and the importance that going to college would have for mentees, as well as for their families. Yet MANOS mentors were also familiar with pressures to succeed academically despite limited ability of parental involvement. Nineteen-year-old mentor Leti expressed her position as cultural mediator at MANOS:

As a daughter of immigrants I understand the situation that both the children and parents in this mentoring program go through. My parents always wanted to be more involved in school activities, but the language was a serious barrier for them. At MANOS I provide the help that my parents were never offered. I love most helping out children. It’s important that our youth learn to value education at a young age and become empowered to promote positive change in our world.

Leti identified with the predicaments of both second-generation children and their parents, which pointed to larger educational issues concerning bilingualism and community engagement. As a mentor, she showed support for families through her cultural sensitivity and empathy. Leti was one member of a team of MANOS mentors who anchored the interplay between family, educational support, and institutional guidance. As Leti indicated, MANOS’s educational outreach model opened lines of communication between volunteer mentors and families about the schools and their opportunities. Culturally sensitive mentors like Leti brokered the immigrant bargain between MANOS families facilitating alignment between the aspirations and goals of parents and children. MANOS mentors also became supportive literacy brokers in the lives of the youth and parents who looked to educational success as a life necessity. They mediated parental expectations, youths’ aspirations, and the realities of miscommunication in families. MANOS mentors cultivated a community through academic participation closely allied to Mexican identity, thereby encouraging a sense of value for the immigrant bargain as a political tool for—and the everyday reality of—immigrant families.

MANOS demonstrated how a safe space outside of a school context promotes open discussion about education for students and mentors to dialogue about the immigrant bargain and schooling. Understanding the emotional and linguistic levels involved in the immigrant bargain deepens the complexity of how adults empathize with second-generation youths grappling with their family migration narratives and academic-professional aspirations. For the children of immigrants, superación narratives are equally self-reflexive projects. Their personal aspirations, however, sometimes come with heavy expectations from the preceding generation. Children use the immigrant bargain as a way to either motivate themselves to try harder or as an additional way to distance themselves from their immigrant identities when plagued with survivor guilt. Unfortunately still salient, this discourse is a historical remnant of an assimilative melting pot American dream assuming that family connections and home languages will evolve or progress toward English as the generations work forward to realize increased opportunities for superación, eventually achieving their aspirations. While this may inevitably be the case, the social pressure to deny the strengths of family happens down at the level of accent.

When examining educational statistics for the children of immigrants, certain trends emerge nationwide. For example, there is increased probability for second-generation children to grow up immersed more in English than their parents’ home language. There is also the greater probability that bilingualism would, by the third generation, lead to monolingual English dominant literacy (Montrul 182; Portes and Zhou 88-89). This intergenerational trend toward monolingualism asks us to consider how immigrant language-minoritized parents remain connected to their children’s educational literacy growth. How can parents maintain high expectations, model literacy practices, and stay as integral and connected through bilingualism if their command of English gets classified as “deficient” by monolingualized educational standards?

However, for 36-year-old MANOS mother Victoria, who had undocumented status, her son’s English literacy took precedence. Learning English, she said, was her nine-year-old son Marcos’s way of defending himself in case something should happen to his parents. When speaking of her reasons for being strong and continuing to work despite feeling tired or ill, Victoria turned to some of the realities she faced as an undocumented immigrant with a son who is a US citizen. According to Victoria she continually reminded Marcos that,

le digo a él que el que de verdad piensa, pues estudia. Dice que quiere ser un buen estudiante. Que va a tener algo. Una carrera, dice. Le digo que tengo que ir a trabajar y tener mucha fuerza porque si voy a trabajar, le digo, entonces puedo darte lo que necesites, mijo. Te apoyaré, le digo. Hasta en este lugar, le digo, a menos que los de migración nos echen pa fuera, y en ese caso, pues nos iremos.

I say to him that the one who thinks, studies. He says he wants to be a good student. That he will have something. A career, he says. I tell him that I have to go to work and have lots of strength because if I go to work, I say to him, then I can give you whichever things you want, my son. I will be here, I say to him. Even here I say to him. Unless immigration kicks us out, and in that case, we will leave.

Marcos flipped through a Spider Man coloring book as his mother said this. In later interviews with Victoria and Marcos, I came to learn more about how Marcos and his family viewed literacy education, and how his mixed-status citizenship from his parents was something he knew a great deal about. Through living in a mixed-status family, Marcos had understood the outlines of immigration and the threat of his parents’ deportation for years. Over those same years the details had become more familiar, and he had become increasingly more knowledgeable of the potential consequences deportation would have on his family. In situations like Marcos’s, the immigrant bargain took on a different guise, not only again between nations, but also distinct in a Mexican variety guised in “illegality” or permission to undertake the American dream in the first place.

For educators, it’s important to understand the complexities of how the immigrant bargain and survivor guilt deepen the familial responsibilities immigrant students face. Educators aware of its importance can connect with students and mentor them in meaningful ways, even if not of the same racial or ethnic group (Louie 170). Finding commonalities among immigrant bargainnarratives for children and parents means sometimes untangling perceptions of how language, social class, and nation affect power relations and constitute social categories and stereotypes. The cross-generational immigrant bargain needs to be approached with sensitivity by educators and agencies dealing with immigrant families, as it is a site of potential conflict among children and parents negotiating their distal and proximal relationships to English and the immigrant bargain. Likewise, school districts should further invest in neighborhood programs like MANOS that perform vital services by mentoring families to meet their academic and developmental needs (171). These services are obviously indispensable and in preciously short supply in New York City’s low-status immigrant communities.

Building on the strengths of students and families like those at MANOS means finding links between the profound resources of universities involved in literacy research, community outreach, multilingual teacher training, and student mentorship programs for future teachers. Building sustainable links could potentially mean longitudinal fieldwork to gain rich qualitative data for literacy analysis and for theorizing pedagogical methods. As the translanguaging event about the immigrant bargain demonstrates, narrating situated literacies as dynamic social practices that broker, shape, react to, and redistribute linguistic power in local communities opens literacy research into richer qualitative detail into the expansive literacy repertoires of students and communities. Finally, connecting research to expressive literacy projects for students turns to the literacy gifts of immigrant communities as sources of pride and identity.