Abstract

This article theorizes the development of a hybrid literate identity—one of both reader and writer. That is, prior to the emergence of social and digital media, the act of meaning-making in models of audience and writing developed in or emerging from the social turn in composition were more heavily dependent on the writer. Based on analysis of wiki talk pages, I describe a model of writing that accounts for “readers-as-writers.” Consequently, this article builds upon audience scholarship to develop a “hypersocial-interactive model of writing” to help us to better understand possible reader and writer roles in digital writing environments.

Keywords: audience; authorship; collaboration; collaborative writing; digital writing; literacy; literacy sponsorship; participatory culture; wiki

Contents

Hypersocial-Interactive (Wiki) Writing

Readers-As-Writers in the Hypersocial-Interactive Model

Introduction

It is becoming abundantly clear that a shift in literate identity parallels developments in new media as people both young and old move into online communities populated with writers. Indeed, we all are increasingly called upon to write in a variety of contexts and to a variety of audiences, and how we teach and discuss audience should account for the emerging ways meaning is negotiated via the newly possible reader/writer relationships that we encounter through new media. Wikis are one location of literate activity where we can observe what is in the words of Andrea Lunsford, “a literacy revolution the likes of which we haven’t seen since Greek civilization” (Lunsford qtd in Thompson). Informed by my use of a discourse analytic approach (Gee) to examine roughly 120,000 words of written collaborative talk by more than 500 Wowpedia community members about the writing of 12 featured articles, I offer sample case studies that strongly suggest the need for a new model of audience.

Like other rhetorical concepts in the discipline, audience occasionally surfaces as a major concern; accordingly, conceptions of audience shift with changing scholarly epistemologies. Current models, developed in and emerging from the social turn in composition, remain essential to our understanding of audience and specifically important to the model I suggest in this essay. As Martin Nystrand, Stuart Greene, and Jeffrey Wiemelt note, we have increasingly viewed texts as sites of interaction and described writing and reading processes as fundamentally social activities. This insight remains central to our understanding, as at each juncture we refine our conception of audience, more and more decentralizing the writer as the sole arbiter of meaning. Yet the case is that, more often than not, audience continues to be consigned to what I call “writing-about” or “responding-to” frameworks.

That is, our audience scholarship most often indicates that, from the writer’s perspective, audience is something written to and for; similarly, from the position of audience, readers can become writers by responding to and writing about what others have written. For example, in their oft-cited landmark 1984 article, “Audience Addressed/Audience Invoked” (AA/AI), Lisa Ede and Andrea Lunsford made strides in offering a model for defining audience that accounts for its “richness” (156) by placing past models of audience into two rubrics that represented composition and rhetoric’s central perspectives: audience addressed and audience invoked.

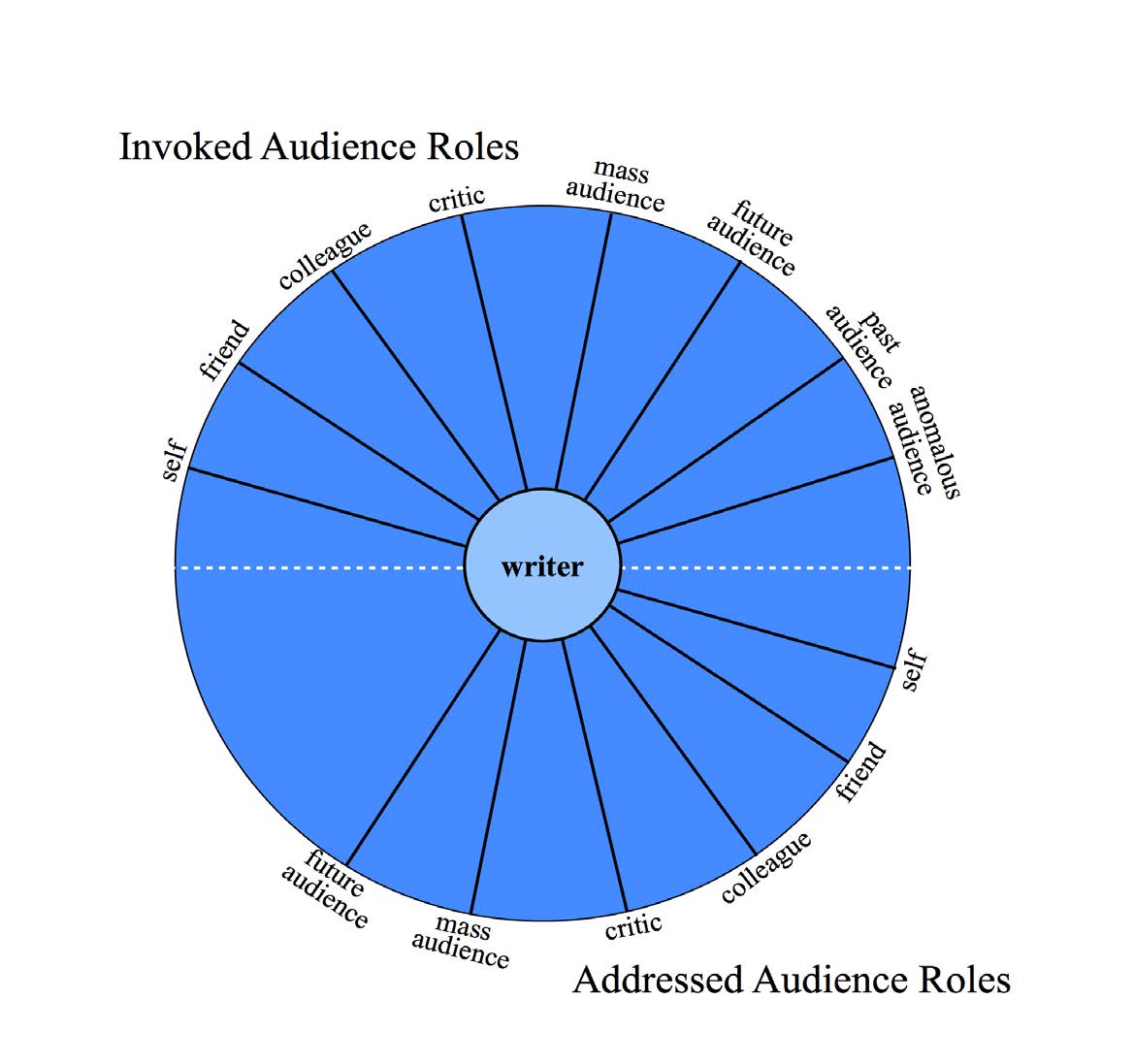

While ultimately complicating both perspectives to synthesize a concept of audience that accounts for the various roles audience might take on, Ede and Lunsford’s representation of audience emphasizes a writer who “both analyze[s] and invent[s] an audience” (163) and “establishes the range of potential roles an audience may play” (165-66). Even when writers respond to readers, writers interpret suggestions and may choose to incorporate them or not. The writer still has ultimate authority over the text. The writer is literally at the center of attention (see Figure 1). With all the possible audience roles available to readers, meaning still primarily moves from the writer through the text to the reader.

Figure 1

Ede & Lunsford's Concept of Audience

Copyright 1984 by the National Counsil of Teachers of English. Used with permission

Copyright 1984 by the National Counsil of Teachers of English. Used with permission

In the late 1990s, Robert Johnson worked explicitly to counter such writer-centric models and to describe an alternative strategy to ensure writer/reader convergence, specifically within the context of technical communications and usability testing. Johnson explains that in his “Audience-Involved” model, users can play a vital role in the process of writing technical documents (e.g., instruction guides).

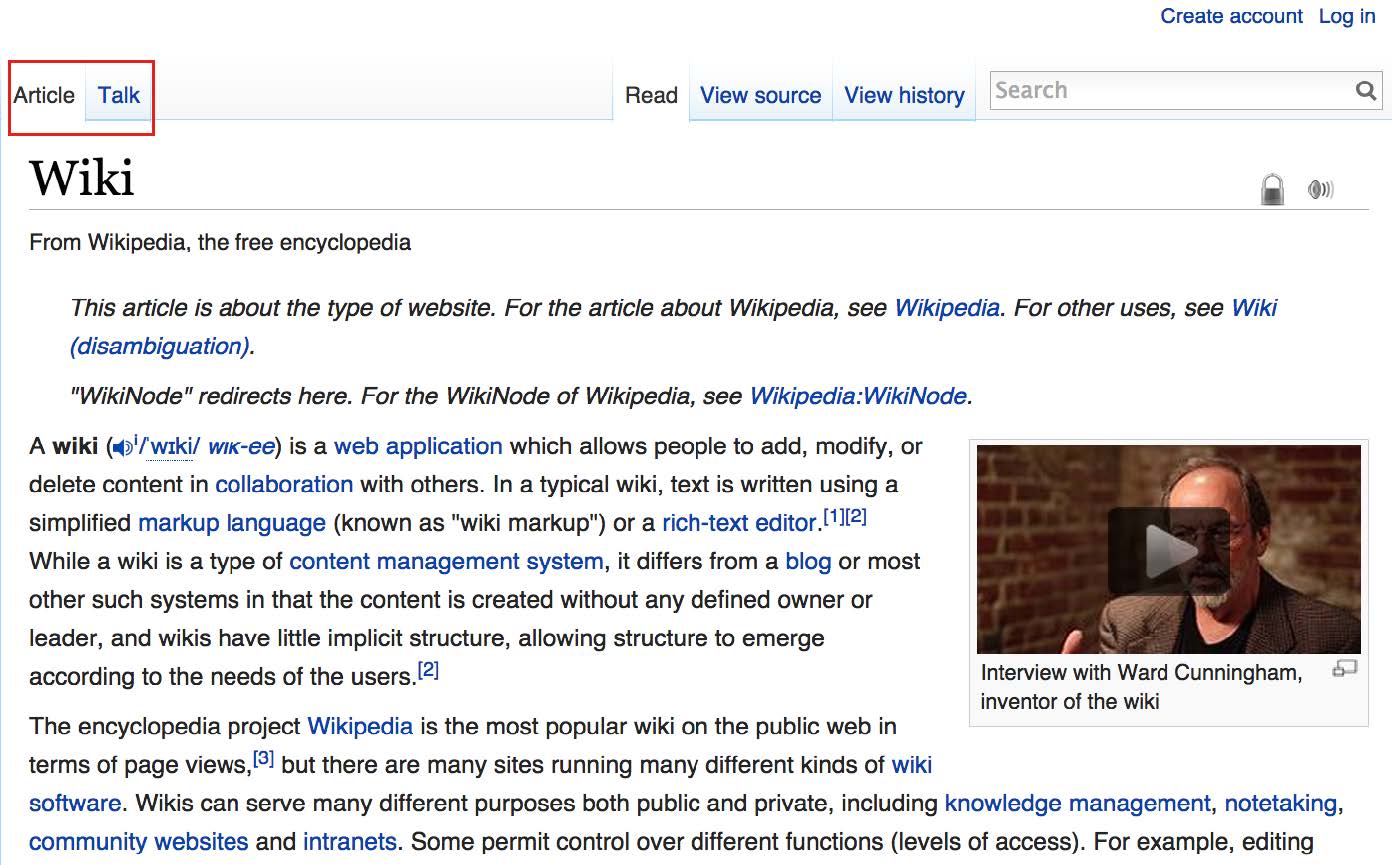

With the development of new writing technologies, allowing for new kinds of texts and new kinds of relations between readers and writers, come new literacies and new literate identities. What my research of wikified-writing shows is that reading and writing on Wowpedia shares features of Johnson’s model; it is certainly not writer-centric. On the contrary, Wowpedia often involves a process of learning to be both reader and writer of articles through a process of enculturation that for the most part happens on “Talk” pages, the tab nested behind the “Article” page we see when visiting Wikipedia, for instance (see Figure 2). Consequently, the conditions of this wiki-mediated writing calls for a model of writing that can be used to describe and theorize audience as it manifests on wikis—one that is not constrained by the legacy of print. In other words, wiki writing (or writing similar to it) may soon become commonplace, and writing researchers and teachers need a way to explain how readers and writers interact with each other and create meaning.

Figure 2

Wiki article tabs; “Talk” page tab.

The site of my study, Wowpedia.org, is a geographically-dispersed writing community that works on researched encyclopedic wiki articles regarding the fictional Warcraft universe that appears in video games, novels, comics, and table-top RPGs.1 There are of course varying degrees of collaboration on particular wikis; here, when I speak of wikis generally, I speak of those familiar to most, those which “anyone can edit” (Wikipedia; Wowpedia). As a site to study literacy activities, Wowpedia’s strength—beyond its importance as an artifact of “participatory culture” (Jenkins et al.)—is that it offers a relatively narrow focus on all things Warcraft, whereas Wikipedia, for instance, presents challenges due to its size and scope; in addition, Wowpedia has a significantly smaller number of contributors than Wikipedia.2 With its common goals, content knowledge, lexis and genres, and participatory mechanisms, Wowpedia can be classified as a discourse community (Swales), whereas it could be argued that Wikipedia may be made up of many topically focused discourse communities. For reasons such as these, I do not claim that the patterns of collaborative writing on Wowpedia are generalizable, even though many of the community’s practices were borrowed and adapted from those first appearing on Wikipedia, as many encyclopedic wikis have done since Wikipedia’s inception. Nonetheless, Wowpedia is a particularly rich case of a wiki that follows what we might call the editable-by-anyone tradition.

Wowpedia’s community is one in which more experienced contributors and various types of administrators play more or less strong roles in the editing process, often asking questions about edits made and offering suggestions for edits. As I will show below, these administrators often work hard to make space for newcomers to become writers, while also working to make newcomers effective collaborators; in effect, they act as literacy sponsors (Brandt, “Sponsors”). Furthermore, in closely attending to the impact of modern writing technologies, we can observe how Wowpedia’s contributors play roles in what Deborah Brandt has called the rise of mass literacy: “We have always assumed that writers would be few and readers would be many. But there’s lots of evidence now that writers are becoming many” (“At the Dawn” n.p.). Therefore, as more and more people participate in online writing spaces, we might assume there will be more and more opportunities for people to become literacy sponsors. This idea of literacy sponsorship, while not the focus of this article, clearly has connections to the literacy practices on Wowpedia. For Brandt, sponsors are “any agents, local or distant, concrete or abstract, who enable, support, teach, and model, as well as recruit, regulate, suppress, or withhold literacy—and gain advantage by it in some way” (19). In this way, sponsorship with regards to Wowpedia can at the very least be traced back to include Wikipedia and the development of the Mediawiki platform Wowpedia uses; the GNU general public license under which Wikipedia originally published and Wikipedia’s more recent use of a Creative Commons license; and Ward Cunningham, the programmer who developed the first wiki for collaboration activities.

Naturally then, wikis are built on a foundation of technological “affordances” (Gibson) that facilitate collaboration, while the collaboration of users is framed by a particular community’s social structures and conventions (Barton, “Is There a Wiki”; Hunter). Based on noted technological and social foundations of wiki writing in various online communities and classrooms, several scholars over the last decade have noted that wikis blur the boundaries between writer and readers (Barton; Cummings, Cummings and Barton; Hunter; Purdy; Vie and deWinter). This is exactly the kind of partnered writing to which Lunsford and Ede refer to when speaking of their own collaborations, seen in the light of what digital, networked writing allows:

We have come to see that what we thought of as two separate strands of our scholarly work—one on collaboration, the other on audience—have in fact become one. As writers and audience merge and shift places in online environments . . . it is more obvious than ever that writers seldom, if ever, write alone (“Among the Audience” 46).

Lunsford and Ede clearly acknowledge that people can play both roles (and in my reading they imply holding both roles at the same time). What is lacking, however, in our discipline’s audience scholarship—even that on digital writing cultures—is a consideration of author and audience and writer and reader beyond either/or positions, i.e., writing-about or responding-to frameworks.

“What is lacking, however, in our discipline’s audience scholarship— even that on digital writing cultures—is a consideration of author and audience and writer and reader beyond either/or positions, i.e., writing-about or responding-to frameworks.”

Those who have written on the subject of wikis find these frameworks still operating as the warrants for composition and rhetoric’s disciplinary assumptions regarding authorship, audience, and collaborative writing—which continue to form the basis for writing instruction (Barton,“The Future”; Cummings and Barton; Cummings; Hunter; Garza and Hern; Lundin; Purdy; Vie and deWinter). As a whole, these scholars explain that many of the practices on wikis such as Wikipedia align with what we value in the teaching of writing, for example, an emphasis on peer review and collaborative processes of knowledge construction and text production. Further, wiki writing destabilizes student-as- writer/teacher-as-audience roles (Barton, “The Future”; Cummings; Vie and deWinter). Therefore, it is argued that wikis allow students to develop richer views of writing as a social act in ways conventional composition instruction does not because wikis can challenge writers accustomed to writing in contexts with more tightly controlled text production.

For example, James Purdy and Rik Hunter both show how wiki communities such as Wikipedia and WoWWiki encourage readers to contribute to and improve ongoing and pre-existing articles— a situation in which engaged readers also become co-writers (“When the Tenets”; “Erasing ‘Property Lines’”). However, our models of audience and research on the nature of those collaborations have yet to reflect the nature of the new reader/writer relationships on these sites. Such theorizing requires analysis of actual discussions between wiki contributors and how they impact readers becoming writers. It is in contributors’ talk about writing where we can appreciate most thoroughly how audience works in a space in which individuals can on their own take up the reins of co-author in a context in which anyone can edit. At stake is developing a more sophisticated understanding and theory of audience to keep pace with the development of digital literate identities.

In this article, I develop a hypersocial-interactive model of writing to account for the literate identity I see emerging from the confluence of technological- and social-empowerment of individuals, i.e., readers-as-writers. A reader-as-writer can make meaning not just in the process of reading but also by interacting with readers and writers to physically change a preexisting text written by others, thus exemplifying how “writers and audience merge and shift places” (Lunsford and Ede 45).

For audience scholarship, wikis are clearly not the only digital space where we can observe increased writer/reader interaction (e.g., comments and discussion on blogs or peer review feedback on fan fiction websites), but I contend that these cases of readers-as-writers at work on Wowpedia reflect a hybrid identity on the farthest end of the spectrum from that of the romantic idea of individual authorship. Therefore, in my view, wikis offer a most profitable opportunity to revise our theories of audience, which have yet to catch up with this particular writing activity. In brief, a wiki-based writing project and community of writers can afford an audience with more active, collaborative potential in the process of meaning-making.

Hypersocial-Interactive (Wiki) Writing

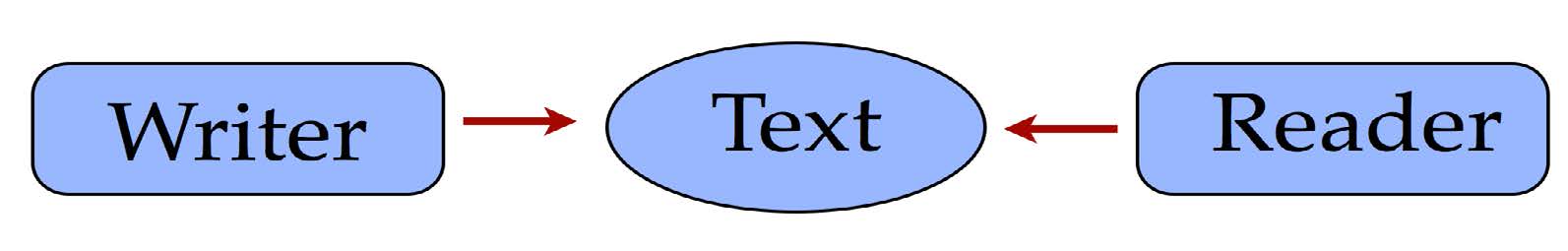

Figure 3

Johnson's Audience-Involved Usability

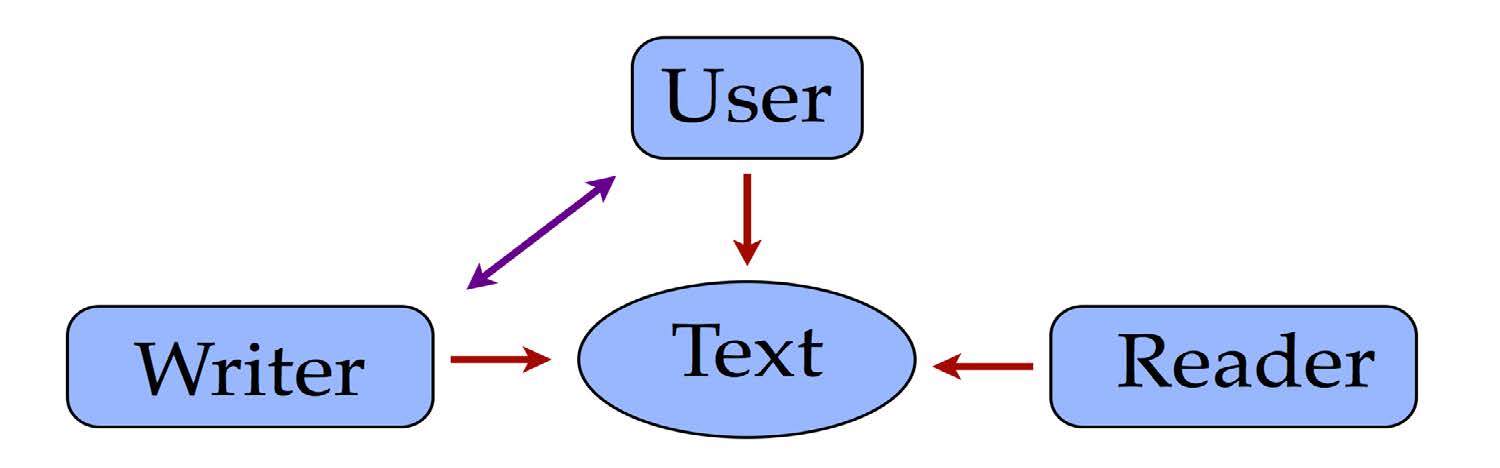

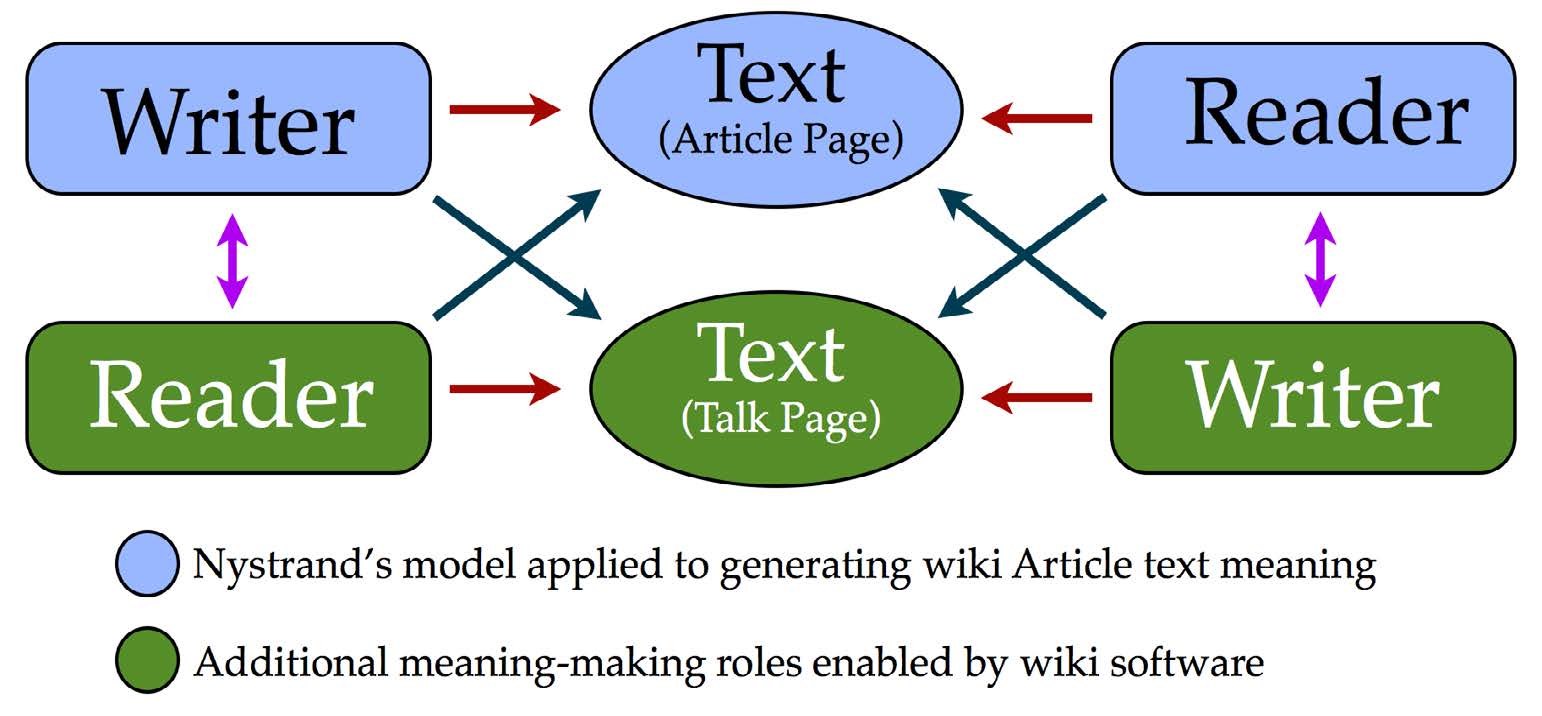

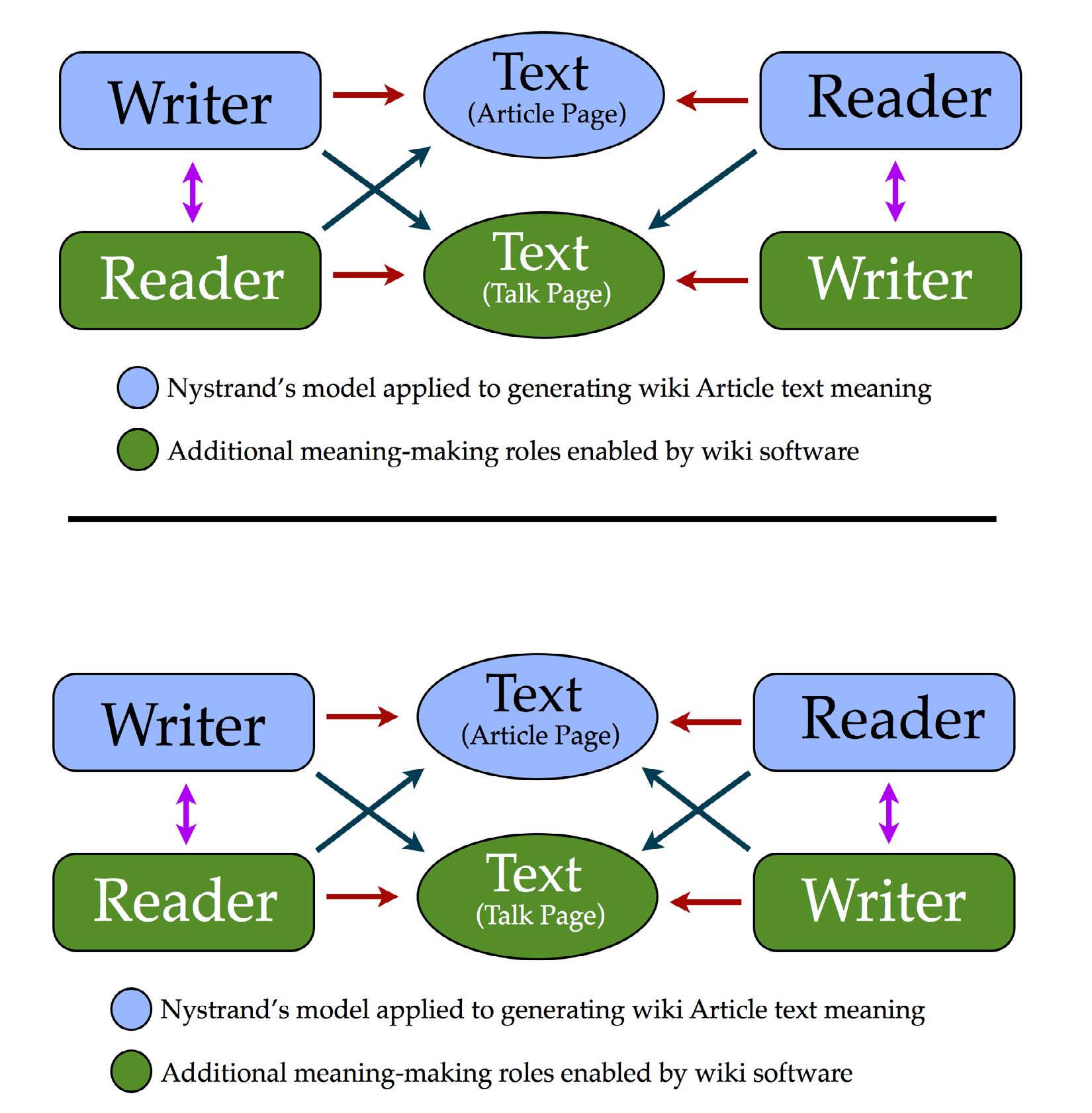

Through my focus on audience, I propose a conceptual model of writing that builds upon the models of Ede and Lunsford, Nystrand, and Johnson (see Figures 1, 3, and 4). However, in constructing my hypersocial-interactive model of writing, I want to rely more heavily on Nystrand’s social-interactive model of writing because it seems the most promising from which to develop the concept of readers-as-writers. Nystrand’s model places the text (i.e., the site of meaning-making) in between writer and reader positions. For Nystrand, the text becomes a site for interaction between readers and writers from which meaning arises, even though he and Himley explain,

[w]riting is obviously not interactive in the behavioral sense that writers and readers take turns as do speakers and listeners. [. . . ] All language—whether written or spoken—is interactive in the abstract sense that its use involves an exchange of meaning, and the text is the means of exchange (198).

Nystrand’s model, then, is ideal for exploring wiki writing where the potentiality of interaction in behavioral and abstract senses exist.

In Nystrand’s work (and that of Nystrand and Himley), writers and readers go through processes of assuming knowledge and expectations and predicting purposes: “Meaning is said to be a social construct negotiated by writer and reader through the medium of text, which uniquely configures their respective purposes” (66). In this model, when writers fail to anticipate all of the readers’ needs, discourse might fail to have the intended effect or be misinterpreted. The smaller the sphere of convergence between writer and reader understanding, the better.

Figure 4

Social-Interactive Model of Writing

Reprinted from Written Communication, 6.1, Martin M. Nystrand "A Social-Interactive Model of Writing," 66-85,

Reprinted from Written Communication, 6.1, Martin M. Nystrand "A Social-Interactive Model of Writing," 66-85,

Copyright 1989, with permission from Sage.

In this social perspective, the success of writer/reader interaction remains largely the responsibility of the writer. That is, because writers and readers are not present in the same space and/or time, writers must work to get “in tune with their readers” and “recognize where to elaborate, where to abbreviate, where to paragraph, and so on. [T]he character and conduct of discourse are governed by the conversants’ expectations for understanding one another” (Nystrand and Himley 199-200). Writing as communication, then, depends on “reciprocity” (Nystrand and Himley 202). Readers can make assumptions about a writer’s purpose, and writers can make assumptions about readers’ knowledge and expectations: “Texts have meaning not to the extent that they represent the writer’s purpose but rather to the extent that their potential for meaning is realized by the reader” (Nystrand 76). Therefore, according to Nystrand and Himley and their contemporaries, social context matters to a great degree, and an effective sense of audience develops from a writer’s membership in any number of discourse communities (Gee; Johns; Swales); successful communication emerges from writers’ and readers’ matching or overlapping memberships that allow for “mutual frame[s] of reference” (Nystrand 79). These transactional frames are the foundation upon which reciprocity is built, and the principle of reciprocity undergirds how we currently conceive of and teach audience. However, in Ede and Lunsford’s and Nystrand and Himley’s social perspectives, writing remains to a large degree what Kenneth Bruffee calls “a displaced form of conversation” (“Collaborative Learning Mankind” 641). Writing is largely in the hands of individual writers because writers and readers most often make meaning of texts in separate places and times. Readers are left with limited power to write about or respond to the texts they encounter.

A smaller sphere of convergence in meaning-making is just what Johnson tries to establish with his audience-involved model. User testing acts as a mechanism for the negotiation of meaning between writers and users. By physically being made a part of the writing process, users “challenge the role (and power) of writers as it encourages a reciprocal and participatory model of writing unlike that usually explained in general composition and rhetoric studies” (362). My understanding of where Johnson finds fault in models such as Ede and Lunsford’s is that meaning-making is still seen from the writer’s point of view (363). Readers are largely virtual as opposed to actual, as in his model, and lack power to affect text production or build reciprocity. He asserts that we need to understand the production of discourse from the perspective of “an actual living, breathing figure” (363). That is, audience has been for the most part kept at a distance from the writer; “they are only written or spoken to, not with” (Johnson 363, emphasis added).

For the most part, I believe Johnson gets this right with his model of writing. The strength of Johnson’s audience-involved model is that it includes the active participation of users in textual production (I also think it fair to extend his model to peer review readers in collaborative writing groups, for instance). And because audience is present and active in his model, we can easily see a connection between the audience-involved model and wiki writing. Meaning is negotiated between writers and actual readers, but wiki-writing simply affords deeper interactiveness and the capacity to take on the identity of reader-as-writer.

Nevertheless, Johnson’s model is ultimately limited by the fact that even with user-testing, there is a virtual audience of users/consumers/readers who will eventually engage with a text after user-testing is completed, and these readers (at the time of Johnson’s article, at least) do not ordinarily have easy access to the writers who might then revise a text. Users might respond to or write about a text by sending letters or emails or even posting feedback on a product’s or company’s website or Facebook page, but this would not promise (timely or immediate) change in the text of a confusing user manual, for instance. The audience-involved model, therefore, hits the same snag as those models Johnson critiques. As George Dillon puts it, “the meaning of the text is not on the page to be extracted by readers; rather, it is what results when they engage . . . texts for whatever purposes they may have and with whatever knowledge, values, and preoccupations they bring to it” (qtd. in Kroll 178). At the end of the day, in the audience-involved model writer and reader go their separate ways, and the writer remains at the helm of text production and steps away from writer/ reader involvement once the text is circulated, that is, published.

As my work shows, readers play a larger role in making meaning on Wowpedia, and the hypersocial-interactive model of writing (Figure 5) is attuned to this new condition of literacy. Therefore, it maps well onto Nystrand’s process for the text-mediated exchanges of meaning between writers and readers. Nystrand’s communicative process is, on Wowpedia, augmented through the practice of more or less rapid mass collaborative talk (between actual readers and writers) and a reader’s ability to edit previously existing text written by others. As mentioned above, many have discussed this ability of readers to edit, but little has been said about the actual process of knowledge construction as it plays out behind the scenes on talk pages.

Figure 5

HyperSocial-Interactive Model of Writing (as observed on wikis)

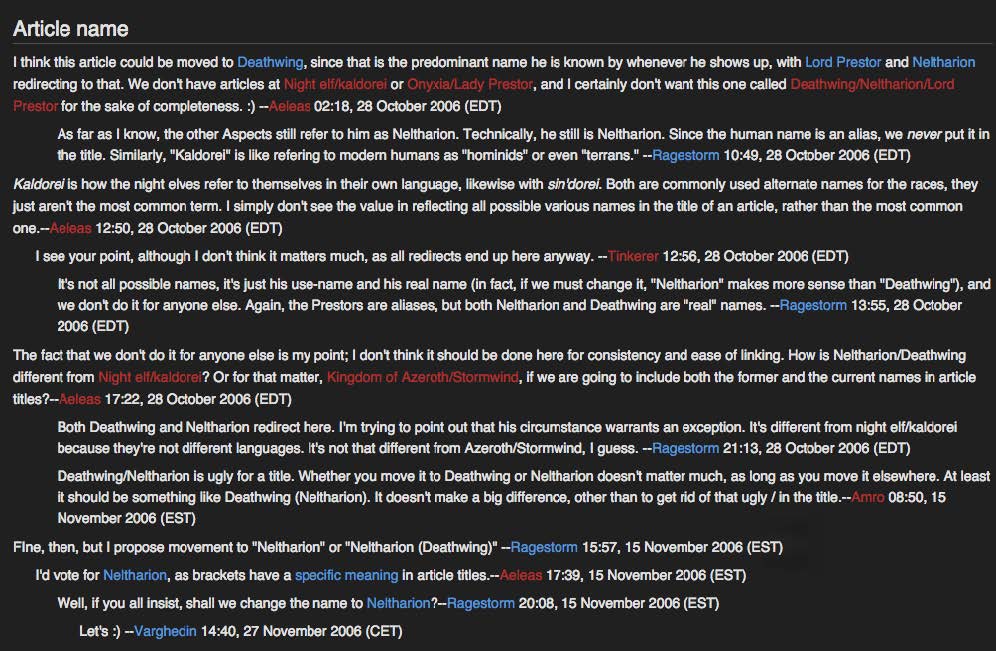

On wikis such as Wowpedia (e.g., Wikipedia), these pages gives us access to contributors’ collaborative talk: commenting on writing, taking up the reins of writing, and interacting with other readers and writers. Nested behind each article there exists a page dedicated to talk about improving articles. The talk page (see Figure 6) is a space where readers and writers discuss what is, could be, or should be in articles. This talk—this writing about writing—is not so different from previous audience activities. Indeed, Wowpedia talk pages are not so different from the marginalia in the medieval codex, described by Jay Bolter: “The center of the page contained the more ancient and venerable text, while the margins offered explanation and commentary added by one or more scholars” (683). As with these marginal notes (written by numerous people over centuries), talk pages are sites of “interpretive material” (Bolter), for example, offering a reading of or judgment on the article.

An important difference, however, is that talk pages also allow for multiple readers to work collectively through problems of interpretation in an article’s text at the same time and in the same space—also interacting with those who have taken on the role of writer—in order to ask questions about the content of the article or a sources used3. Further, as in writing groups, writers can interact with readers by asking for feedback before or after making changes to the article and by reporting having made changes to an article. Talk pages, then, are where readers and writers interact and generate (and negotiate) meaning.

Figure 6

Exerpt from talk page discussion

The distinction I am attempting to draw between Nystrand’s model and my own is that while wiki articles continue to serve as bridges for meaning-making between writer and reader as described by Nystrand, talk pages allow for actual readers and writers to work out meaning together—synchronously or asynchronously on the talk page. This model of writing also includes the power of readers to become writers. In this way, the editability of articles and talk pages add another layer of interactivity for which Nystrand’s model cannot account. It is these social features of collective meaning-making and collaborative editability that the concept of reader-as-writer seeks to represent. This concept, therefore, alludes to prior theories of writing as fundamentally social, even in situations in which writers never interact with actual readers and readers are assumed to make meaning of the texts they encounter; I include hypertext theory in this body of thought. This, then, is where writing on Wowpedia distinguishes itself: not only can readers and writers interact during the meaning-making process but also readers can become writers and cowriters.

Readers-As-Writers in the Hypersocial-Interactive Model

In this section, I offer case studies from Wowpedia talk pages that illustrate how “writers and audience merge and shift places” (Lunsford and Ede 45) on this wiki. On Wowpedia we can find readers navigating their way through rhetorical situations vastly different from those based on print media. Readers are valued by members of Wowpedia not just for their commentary on writing but also for their potential to become co-writers. As I will show, in collaborative writing on Wowpedia, readers can take on the social roles and activities we associate with peer reviewers and writing partners—sometimes on their own and at other times through encouragement and socialization by veteran contributors. In short, the hypersocial-interactive model of writing is my effort to explain a type of reader, a reader-as-writer, who can make meaning not just in the process of reading but also by interacting with readers and writers and physically changing a preexisting text written by others, thus embodying Lunsford and Ede’s observation about twenty-first century writers and readers.

“In short, the hypersocial- interactive model of writing is my effort to explain a type of reader, a reader-as-writer, who can make meaning not just in the process of reading but also by interacting with readers and writers and physically changing a preexisting text written by others.”

Readers on Wowpedia can comment on writing and so take on the role of reviewer much as they do in other contexts, such as blogs and fan fiction sites as well as voluntary and school-sponsored writing groups (Bruffee, “Collaborative Learning”; Gere and Abbott; Nystrand and Brandt; Spigelman, “Habits,” Across). A reader responds to someone else’s writing with praise, negative criticism, questions, and suggestions, and, in doing so, these readers’ talk page contributions are collaborative acts meant to improve articles. Take for example a conversation on the “Medivh” talk page between Lijaka (who had never edited an article on Wowpedia) and Baggins and Sky (who have each contributed over 25,000 edits of various kinds, hold administrative roles, and took part in editing this particular article). Lijaka starts the discussion thread by asking about conflicting information present in the “Medivh” and “Aegywnn” articles:

Hi, I’m not sure which one is correct, but thought I’d point out that on this page it states Medivh’s coma lasted 20 years, but on the Aegwynn page, it states he awoke 6 years later. —Lijaka 18:11, 18 June 2007 (UTC)

[The] Six year reference was in Warcraft 1 manual [a video game]—pages 21, 22, and possible other sources. The 20 year reference was from Cycle of Hatred [sic; this is the title of a novel]? I’d just explain the differences between the two stories somewhere, and add the citations. —Baggins 22:18, 18 June 2007 (UTC)

Considering how poorly blizzard [Warcraft video game developer and publisher] is at keeping their timelines consistent, its [sic] possible that a mistake may have cropped up in Cycle of Hatred [sic] as well. We may never know which case it was. —Baggins 22:22, 18 June 2007 (UTC)

20 year reference is in The Last Guardian [sic; title of a novel]; don’t ask me to find the page. :( —Sky 03:03, 23 June 2007 (UTC)

This is why I tend to avoid using specific dates on article pages, :p . . . Better to mask them with terms like, decades, several years, etc..... —Baggins 15:02, 27 July 2007 (UTC)

Similar to the “users” Robert Johnson describes as giving feedback to technical writers in his audience-involved model, Lijaka here pinpoints an inconsistency between these two articles that might create a problem for other readers. In contrast to the process Johnson describes—a process in which a text’s final draft is published and in most cases cannot be easily updated and republished—a wiki article can be updated easily and quickly as often as needed. That is, if we imagine the “Medivh” article were published in a print or proprietary form, Lijaka would have had to send in an email to the publisher, and then, if the suggestion were accepted, Lijaka would then have to wait for the next edition of the print encyclopedia to see the problem addressed.With wikis, however, the ability to leave feedback easily on an article’s talk page is amplified by the access Lijaka has to all of the articles’ writers—as long as they are paying attention to the talk pages and are willing to respond. In this way, both the wiki as a collaborative technology and the value community members place on feedback contribute to the participatory powers of readers to shape revision.

Moreover, Lijaka easily could have edited both pages and made the articles consistent. However, this technical affordance allowing anyone to edit does not always mean a reader will become a writer. In this case, Lijaka did not. It is not clear why. Perhaps Lijaka held a conventional notion of audience. He or she, as a reader, never thought to make edits to the page. In the end, Lijaka never responds to Baggins’ and Sky’s posts, so it is equally possible that Lijaka simply did not revisit the talk page after posting his/her comment and never saw Baggins’ and Sky’s responses. Regardless of the cause, Lijaka’s lack of participation in writing was not because he or she was constrained by the technology or community—all readers are encouraged to edit. Lijaka remains in a reader-as-reviewer position even though Baggins seemingly invites Lijaka to become a writer (see Figure 7 and note that the missing arrow between “reader-writer” and “text (article)” represents the absence of a reader acting as a writer).

Figure 7

The Reader-as-Reviewer role, in contrast to that of the Reader-as-Writer seen below.

That is, in Baggins’ first post, he uses the modal “would,” and in this context of collaborative writing, we can interpret “I’d just explain the differences between the two stories somewhere, and add the citations” to include the conditional phrase “If I were revising this” or “If I were you.” So Baggins’ response can be read as an invitation to edit, and such invitations permeate Wowpedia’s talk pages, some more obvious than others, as with a high-level administrator’s response to contributor js1006:

A pretty small point, but the term “anti-hero” is being misused here [in the “Deathwing” article] http:/en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-hero. Deathwing is a villain and evil, but as the wiki link shows, that is not the meaning of the term anti-hero. —js1006 15:31, 8 September 2007 (UTC)

Agreed. Remove as needed. —Ragestorm 20:28, 10 September 2007 (UTC)

In this case, as with Lijaka, js1006 does not make the changes she or he recommended. I found many more examples of readers acting solely as reviewers of articles. Despite the fact that (1) we can see more experienced contributors encouraging readers to become writers and contribute writing to articles and (2) the wiki enables users to edit, a reader-as-reviewer doesn’t necessarily take on the role of writer.

A few patterns emerge from examining occasions in which readers-as-reviewers pose questions about or identify potential problems with the content of articles:

- a reader-reviewer is often invited to make revisions;

- a discussion motivates others (but not the original reader-as-reviewer) to revise;

- and discussants come to an agreement that edits need to be made which might or might not result in changes being (1) made, (2) made at a later date, or (3) reported on the talk page.

Readers’ access to writers and other readers seems to create an atmosphere in which response to one another is taken seriously. Suggestions are weighed, sometimes by dozens of contributors over the life of an article, and this type of reader/writer interaction is one example of the type of social role associated with readers-as-writers.

More important to hypersocial-interactive writing, of course, is the ability to become a writer and to revise the writing of others. What I call “at-will coauthorship” distinguishes this wiki collaborative writing from other types. This is strongly encouraged by Wowpedia’s “Be Bold!” policy:

If someone writes an inferior article, a merely humorous article, an article stub, or outright patent nonsense, don’t worry about his/her feelings. Correct it, add to it, and, if it’s a total waste of time, replace it with brilliant prose. That’s the nature of a Wiki.

And, of course, others here will boldly and mercilessly edit what you write. Don’t take it personally. They, like all of us, just want to make Wowpedia as good as it can possibly be. (“Be Bold”)

Indeed, Wikipedia’s co-founder, Larry Sanger, attributes the success of Wikipedia to what he calls “good-natured anarchy” and to the fact that wiki software encourages “extreme openness and decentralization” of labor (310). If a wiki is to grow quickly and cover a wide range of topics, it needs contributors who are free to add or edit content when they see a need. These interventions may include adding a reference, reorganizing sections, reverting incorrect edits or those not in line with community standards, or making the language in articles more neutral (i.e., “Neutral Point of View”)4. But while the community “exhorts users to be bold in editing pages” (“Be Bold”), it is with the understanding that new members may not be familiar with established practices, and so guidance is offered on how to interact with newcomers. What follows is only the introduction of a longer article titled “Don’t Bite the Newbies” that outlines what we might refer to as the rules of engagement:

Wowpedia improves through not only the hard work of more dedicated members, but also through the contributions of many curious newcomers. All of us were newcomers once, even those careful or lucky enough to have avoided common mistakes, and many of us consider ourselves newcomers even after months (or years) of contributing. (“Don’t Bite”)

New contributors are prospective “members” and are therefore our most valuable resource. We must treat newcomers with kindness and patience—nothing scares potentially valuable contributors away faster than hostility or elitism. While many newcomers hit the ground running, some lack knowledge about the way we do things.

In part, becoming a reader-as-writer requires learning how to use the wiki to read, comment, write, and collaborate. Take for example, Ellethwen, who was new to the wiki at the time she/he reported a problem in the “Lich King” article: “[The images are] all clustered together and on one side. It looks bad, and it’s pushing down text in Internet Explorer” (“Talk: ‘Lich King’”). Again, this is similar to the type of feedback Johnson describes in usability testing, but there’s one pivotal difference. Because newcomers are valued for the contributions they may make to the wiki, Ragestorm, a much more experienced writer, invites the reader to become a writer: “Fiddle around with them, see what you can come up with. Apart from the infobox picture, none of them are wedded to their location.” When Ellethwen conveys her/his hesitancy (“I’m no good with wiki formatting. I’d probably ruin the article. But if you want me to, I can try”), Ragestorm educates Ellethwen about the wiki technology: “The article can be reverted at any time, so experiment a little—and use the ‘show preview’ button to view your changes before they’re actually saved.” Time and time again, more experienced Wowpedians encourage newcomers to contribute to the writing project by taking on the role of writer by teaching newcomers to use wiki technology. But this ad hoc apprenticeship also includes the socialization of newcomers.

This is why Henry Jenkins et al. argue that new media literacies should be taught as “cultural competencies,” or “ways of interacting within a larger community, and not simply an individualized skill to be used for personal expression” (20). Importantly, these online (writing) spaces, as Michele Knobel and Colin Lankshear describe them, involve both “technical stuff ” and “ethos stuff ” (9). Consequently, becoming a member of the Wowpedia community includes becoming a good writing partner, and this appears to come with experience. In other words, when growing numbers of readers become bold writers on Wowpedia, problems can occur if writers have different visions of what the content of an article should be as well as how the collaborative writing processes work. Successful collaboration occurs on Wowpedia when contributors are closely aligned in the ways they go about getting writing done with others (see Hunter). This alignment becomes more visible when we examine breakdowns in communication resulting from contributors not conforming to the same practices—in terms of generic conventions, for instance, as well as within the process of collaboration.

Take the case of a minor edit war that erupted around the introduction of the “Sylvanas Windrunner” article. It started when Raze deleted a paragraph of information from the introduction (see before and after edits in Figure 8). During the next 20 minutes, Sky reverts Raze’s deletion edit; Raze repeats the deletion. This is finally followed by Sky making a talk page post and a final reversion of Raze’s edit:

Yes, it is redundant [the introductory paragraph Raze deleted]. That is the point of the introduction. It is meant to give an overview of an article, or an essay, or what have you. Mind you, not even all of it is “covered below”. It will be readded. —Sky 07:11, 27 July 2007 (UTC)

I personally find the article way too verbose, loaded with unnecessary details and adjectives & adverbs (her valiant efforts?? She fought valiantly against Arthas?). Here’s an example of the proper format [Raze links to an example article on Wikipedia]. It is much shorter and concise. Personally I think we need to follow this standard. —Raze 07:22, 27 July 2007 (UTC)

Then make it closer to NPOV, if that’s the issue. Deleting the introductory paragraph is silly. —Sky 07:26, 27 July 2007 (UTC)5

This excerpt is from a longer conversation in which Baggins, acting as a moderating voice, also explains to Raze the function of introductions in wiki articles as well as the importance of being “careful of removing unique and cited information if it doesn’t exist elsewhere in the article.” While Sky, a more experienced community member, does tell Raze the deletion was “silly” in the heat of the moment, another member more gently instructs Raze regarding the wiki-encyclopedic genre and its conventions on Wowpedia. Of key importance in this exchange is that Sky never attempts to dissuade Raze from editing. Even after admonishing Raze, Sky in fact, tells Raze to “Make it [the introduction] closer to NPOV.”

Although both Sky and Baggins intend to teach Raze about writing in this genre, Raze has also obtained more important experience in how the talk page plays a crucial role in giving writers a space to work out differences and find solutions. This situation and its resulting discussion come about because a reader was able to become a reader-as-writer.

In part, then, problems arise between contributors when they do not follow established community practices, for example, when making changes to articles and reverting edits without using the talk page to discuss those edits with others. In the next excerpt, Ragestorm points this out to newcomer Peregrine:

What the hell? Ragestorm, I’m getting kind of sick of you deleting everything I do on here; there was nothing wrong with my Illidan Stormrage pic there. Why on earth did you go and get rid of it? ~— Peregrine

[. . .]

I was deleting that picture before you came along, and Kirochi did as well. The problem’s not you, it’s the kriffin’ [fucking] article. —Ragestorm 21:18, 2 July 2007 (UTC)

[. . .]

I’m not going to pretend this was handled properly, but I have a tendency to revert immediately, and you have a tendency to not react [respond] to discussions, so here we are. How does that image . . . show Illidan’s “glory?” —Ragestorm 00:24, 3 July 2007 (UTC) [emphasis added]

It’s such a dramatic screenshot, and I don’t think the blue backdrop ruins it. . . . Hm, would creating a page where players could post their WoW Model Viewer screenshots be some sort of violation? There seems to be a rule to revert every edit I do. —Peregrine

Although posting about edits or potential edits is not a formalized rule on the wiki, these types of announcements about revision ideas and intentions open up discussion and assuage the rancor of others. Equally important, asking about potential revisions ultimately serves a significant function for newcomers in that discussions create opportunities to learn more about not just Warcraft as a fictional universe but also writing about Warcraft on Wowpedia. As Peregrine remarks, “There seems to be a rule to revert every edit I do,” implying that this is not the first time Peregrine has experienced edit reversion. But these previous events have not deterred Peregrine from continuing on as a reader-as-writer. Although Peregrine could have easily read all the key guideline and policy articles that direct editing, learning about rules after making edits rather than before is one method of enculturation in an environment where anyone can edit.

Indeed, posting about edits or potential edits was a pattern I found across talk pages and is especially evident with newcomers. Many newcomers took a more cautious approach that conveys an awareness that one is ultimately working with others. These writers posted questions or proposals concerning potential edits and waited for some kind of endorsement before taking action—either from an administrator or the general consensus of those participating in the discussion. Here is an example:

Is there even a point in having this section [of general information on Illidan]? Other characters don’t have it, or at least the ones I’ve seen. Anything in here can be directly included in the article itself. Also there should be synchronicity between articles, if one has it then all should have it or none should have it. To me it ruins the professional look of the article and makes it seem untidy. I’m not going to delete this because its [sic] a major portion but I would like someone to justify it being here. If not then I’ll delete it. —Noman953, 04:15 23 January 2007 (UTC) [emphasis added]

Noman953’s statement concerning reluctance to delete the section in question would seem to contradict the very idea of being bold that is so emphasized in the “Be Bold!” guidelines. However, what he/she announces as the plan of action in fact falls under the “but don’t be reckless!” subsection of “Be Bold!” Noman953 has clearly learned this step of consulting before editing at some time in the past. I won’t go so far as to claim that Noman953 learned this on Wowpedia; what is of more importance is that this announcement falls in line with the accepted behaviors established for collaborative writing on Wowpedia and with a reader-as-writer perspective on audience. Noman953 does make the proposed edits after receiving feedback from more experienced contributors. His discussion with Kirkburn and Ragestorm typifies reader-as-writers’ mass collaborative processes:

Rather than just being removed entirely, it should be rewritten into a short intro prose covering the important points about Illidan. Certainly at the moment it covers far far too much, is inconsistent and invites the addition of pointless factoids. —Kirkburn 04:37, 23 January 2007 (EST)

Agreed. For the record, “Furion” [a Warcraft character] has one of those as well, but we should compress the info into paragraph format, in the same manner as other pages, such as “Tyrande [a Warcraft character].” — Ragestorm 17:15, 23 January 2007 (EST)

Edits are done. —Noman953, 06:56 23 January 2007 (UTC)

Noman953, as a member of Wowpedia for only a few months at the time of this discussion, is acting in the hybrid role of reader-as-writer. First, Noman953 offers feedback on the writing of others and feels it necessary to check with the community of writers before making what he/she considered would be a major edit. Rightly so, it seems, because Kirkburn next advises a particular revision of the section in question, and Ragestorm offers more specific suggestions. Finally, Noman953 reports having made the edits. As we have seen in the Sky and Raze example, the process of Noman953’s contribution cannot be taken for granted. Reporting edits or intentions to edit appears to play an important role in reducing the chances of misunderstandings and tensions between contributors that arise when anyone can edit at anytime. It is one of the social practices of Wowpedia that keeps collaboration running smoothly. Collaborative writing works because Noman953, Kirkburn, and Ragestorm are able to work well together as mutually recognized readers-as-writers.

Overall, what I have observed on Wowpedia aligns with James Porter’s use of a Burkean- inspired example to describe a social view of composition. Instead of a parlor, he uses as his example a hypothetical attempt to persuade university administration about the need for a writing center. He explains,

As a rhetor I might be changed by, rather than change, my audience.......... I bring pre-texts from another realm, a set of assumptions, beliefs, and the like, that are only partially, if at all, functional in this discourse community I may be successful in reshaping or redirecting the community to see the value of a writing center, but I might be changed by that identification. To change my audience, I have to be willing to change, too. I must accept them as writers and see myself as, in part, audience: thus, the roles of audience and writer, these once separate roles of audience and writer, become blurred, coalesce in the notion of the discourse community. (116)

This process of change in ones (literate) identity within a discourse community also appears to work similarly in the collaborative context of Wowpedia. Over time, newcomers more or less come to act in accordance with shared behaviors and practices regarding collaborative writing—often as a result of ad hoc mentoring by more experienced members. Beyond learning to use the wiki software, newcomers learn to more deftly shift between the roles of reader and writer, in effect “reacculturating” (Bruffee, Collaborative Learning 8) to the circumstances of Wowpedia and becoming members of this knowledge community.

Conclusion

Building on Nystrand’s social-interactive model of writing, in which meaning is negotiated by writer and reader through the medium of text, I have devised a hypersocial-interactive model of writing to account for writer and reader roles in meaning-making on Wowpedia. As a result, within this model I develop the concept of readers-as-writers to describe best what I see as new audience roles that are in the words of Knobel and Lankshear “more ‘participatory,’ ‘collaborative,’ and ‘distributed’ in nature than [those in] conventional literacies. [They are] more collaborative than what was possible prior to the development of new media” (9). My hope is that this model of writing might offer value in thinking about audience with current or yet-to-be-developed writing platforms.

For example, we are beginning to see a kind of reading that becomes more interactive in book publishing. While Clive Thompson complains that currently books are “the only major medium that hasn’t embraced the digital age” (50), he suggests that if publishers want to succeed in the twenty-first century, they need to “stop thinking about the future of publishing and think instead about the future of reading” (50, emphasis added). This future is not one that should be focused solely on the digital delivery of ebooks to Kindles or iPads. That’s simply another distribution channel of media consumption. Instead, publishing’s future is one that depends on how it makes reading more interactive through the use of technology to allow readers to interact with other readers as well as writers.

Thompson points to existent technologies that increase reader/reader and even writer/ reader interaction beyond my case of the wiki. In book publishing, he cites Mackenzie Wark’s use of the CommentPress Wordpress theme developed by the Institute for the Future of the Book. Similarly, Kathleen Fitzpatrick, the current Director of Scholarly Communication of the Modern Language Association, made available a draft of her book manuscript, Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy, on the Institute for Future of the Book website. This platform allowed readers to leave comments on paragraphs, pages, or the whole draft as well as interact with other readers and Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick’s goal in opening up the review process was “to reform peer review for the digital age, insisting that peer review will be a more productive, more helpful, more transparent, and more effective process if conducted in the open.” In this way, Fitzpatrick grants greater partial textual ownership to her readers, at least temporarily.

With regard to higher education, several digital technologies are also being developed by universities as part of digital humanities initiatives that will emphasize the importance of collaborative tools for developing students’ new media literacies. To name just one, MIT’s HyperStudio recently received a NEH Digital Humanities Start-Up Grant to develop Annotation Studio, a tool designed in part for collaboratively reading multimedia, which “will help students develop traditional humanistic skills including close reading, textual analysis, persuasive writing, and critical thinking.” In my mind, developing collaborative mindsets for a digital age is just what web-based, mass-collaborative encyclopedia projects such as Wowpedia already do; higher education is playing catch-up.

Case in point: in her 2004 “Chair’s Address,” Kathleen Blake Yancey argues for a “new curriculum for the twenty-first century” that includes moving beyond “our model of teaching composition” which “(still) embodies the narrow and the singular . . . emphasis on a primary and single human relationship: the writer [student] in relationship to the teacher” (308-09). As she asserts, “[i]n contrast to the development of a writing public, the classroom writer is not a member of a collaborative group with a common project linked to the world at large and delivered in multiple genres and media, but a singular person writing over and over again—to the teacher” (310). If the emphasis of writing instruction is that teacher/student relationship and power dynamic, how prepared for writing in other rhetorical situations can our students be?

As a move towards a more effective curriculum, Yancey advocates empowering students to take advantage of digital writing technologies in order to “create writing publics” (321). Given the writer/reader relations writing technologies such Mediawiki, CommentPress, and Google Apps afford, we can help students understand more fully what being a twenty-first century audience means in terms of Yancey's new curriculum. That is, the norm of what it means to be a reader may come to be increasingly participatory, and if that is the case, students need to be adequately prepared to take on those participatory roles.

In my own teaching of new literacies, I have used Wikipedia as a productive venue for students to experience what a contemporary, empowered audience can do. The assumption is that the audience will participate; however, the audience will need to know how to participate. As I have shown above, when collaboration on Wowpedia is successful, it requires more than simply finding the “edit” button, adding content, and hitting “save”; it requires attention to the social practices of the community. Matt Barton sums this idea up well: “Knowing how to change a wiki page is one thing; knowing how to make an appropriate change that will be accepted by a wiki community is another” (“Is There a Wiki” 178). Wowpedia contributors come to share a communal notion of authorship and textual ownership as well as a willingness to see in their readers as potential writing partners (Hunter). It is from this foundation that readers-as-writers emerge.

“[N]ew media writing may soon become commonplace, and writing researchers and teachers can use the concept of reader-as-writers and the hypersocial-interactive model to explain how readers and writers interact with each other to create meaning in a variety of rhetorical situations.”

For example, one of my students, known as BadgerBuddy on Wikipedia, was an early contributor to the Wikipedia article on Henry Jenkins’ concept of “transmedia storytelling” (we were reading Jenkins’ Convergence Culture at the time). When we began these Wikipedia projects in my composition course in 2007, it seemed enough to emphasize possible co-production of articles—either by creating new pieces or revising existing ones. His individual contributions accreted over time; in this case, his initial additions to “Transmedia Storytelling” were first written over the span of one week. The talk page was empty and remained so. My student didn’t report any need to work with Ill seletorre, the only other contributor, perhaps because the article was at such an early stage of development.

However, I later realized the need to pay attention to talk pages in my teaching. In one instance, a student who passionately opposed popular characterizations of pit bulls as dangerous wanted to work on the Wikipedia “Pit bull” article, which already had a long history of edit reversions (see “Edit Warring”) and has a talk page running back to 2003. Essentially, the student saw areas of the article she felt needed to be revised to reflect reality. She cited sources in her contributions, but this didn’t stop her changes from being reverted and deleted with no communication from the responsible contributors. Might she have been able to prevent these changes if she had instead participated in the talk page first? It’s impossible to say, given the tenor of the many impassioned discussions. But she might have least assuaged her own frustrations by taking on the reader-as-writer identity more fully and attempting to engage others in productive conversation (and there are many productive conversations to be found on this article’s talk page).

I have responded by pushing against the idea that writing the article (or revising it) is the main goal. Instead, I emphasize that, in addition to making edits, students should try to interact with other readers and writers by asking questions about and suggesting revisions. Working to build some consensus through conversation is an important part of the writing process.

In these ways, I see wiki writing running counter to more individualistic systems of text production—including the “narrow and the singular” student (writer) and teacher (reader) relationship Yancey criticizes (309-10) as still dominating in our classrooms—and wiki-based writing assignments, especially those taking place on public wikis, can bring students into closer proximity with audience. Those collaborative acts of writing can include just the sort of interactions I have examined in this article (see Robert Cummings for a well-designed Wikipedia assignment). Such assignments can capitalize on a wiki’s collaborative affordances, making more visible what roles students might play in text production and also how they might contribute appropriately to building knowledge. That is, when students write for public wikis, they have the opportunity to examine and often experience the local social practices firsthand.

However, I do not want what I have written to be seen as advocating for wikis as a panacea for teaching the concept of audience. More generally, in writing instruction, collaborative reading and writing supports the development of literacy skills we already value, and the affordances of new media make can make visible the importance of more collaborative mindsets. In other words, new media writing may soon become commonplace, and writing researchers and teachers can use the concept of readers-as-writers and the hypersocial-interactive model to explain how readers and writers interact with each other to create meaning in a variety of rhetorical situations. What I suggest is giving students opportunities to see how various technologies and social conventions shape literate identities, making possible particular social roles and not others. Wikis do this, but so can many other writing technologies. Studying and participating on wikis just happens to be one way to achieve this goal because we can easily observe and experience how already-published-yet- still-editable-by-anyone texts are not the sole or primary medium through which writers and readers negotiate textual meaning. In this way, the hypersocial-interactive model of writing may prove useful for those seeking to account for and examine the social roles readers can play in the use of digital writing technologies. Additionally, it may well facilitate students’ participation in the dynamic and varied writing publics that inhabit the contemporary technocultural landscape of textual production. Future research might also investigate how the author/audience dynamic found on Wowpedia, a popular culture fan-produced site, might play out in settings with higher stakes such as in professional settings—engineering, medical, legal, etc.—that require texts be written by those with specialized knowledge and in which the consequences can be profound. To offer one intriguing example, we can see how even a traditionally hierarchical organization such as the U.S. Army is attempting to leverage what wikis can offer in terms of collaborative knowledge production (Cohen). The Army’s recent employment of MilWiki for its Wikified Army Field Guide empowers soldiers, “from the privates to the generals,” to update Army tactics, techniques, and procedures from the field collaboratively with the understanding that those in the field need the best and most up-to-date information:

As the battlefield changes rapidly, the field manuals must keep pace. Under the traditional process—in which a select few were charged with drafting and updating the field manuals— the manuals often failed to reflect the latest knowledge of Soldiers on the ground. (U.S. Army).

As an Army veteran, I find it interesting that this site has been developed by an organization that is highly dependent on strict hierarchies, yet from what we know of knowledge production on successful wiki projects, the Army must to some degree rely upon distributed participatory design and collective intelligence, whereas in the past only those recognized as experts were authorized to write the manuals. There isn’t much information available about this project, but it “receive[d the] Army’s top knowledge management honor” (Davidson) and was recognized by the White House’s Open Government Initiative. One question we would need to ask is whether contributors to MilWiki take on more collaborative mindsets than those who had previously been charged with writing the field manuals. Another is whether soldiers are interacting on talk pages. Based on my limited knowledge of the project, it models itself after Wikipedia and uses the same software. In addition, the project’s contributors are evidently a mix of “organizational newcomers or subject matter experts” (Davidson). Therefore, we are talking about more than user testing, and the hypersocial-interactive model of writing and the reader-as-writer identity might apply, if somewhat ironically, in this context.

Following the example of the Army’s Field Manuals, in addition to my study of Wowpedia, it is clear that the future of reading Clive Thompson calls for is already upon us. With wikis, readers can easily interact with writers and other readers on talk pages. As I have shown in this article, writing on Wowpedia goes a step beyond what Thompson describes and Fitzpatrick puts in practice. With tongue in cheek, we might call readers-as-writers, as I conceptualize them, the future future of reading. Contributors’ notions of the nature of audience include the virtual and actual as well as the participatory because wiki writing includes readers becoming at-will coauthors of texts written by others. The implications for the future of reading is that these collaborative processes will be much more productive if those involved know how to effectively participate.

Endnotes

1Wowpedia.org is a project fork of Wowwiki.com. In this case, a fork, commonly associated with open source software development, is a legal copying of all of Wowwiki’s content to start a new wiki, as allowed by Wowwiki’s Creative Commons License. Wikipedia, for instance, operates under the same license. This forking occurred in October 2010 after a dispute between the most of the Wowwiki administration—including the wider community—and Wikia, the wikifarm hosting Wowwiki. I am currently investigating this event. In the process of this forking, most of Wowwiki’s administrators and many of its editors moved to Wowpedia. In addition, though my data collection for this article occurred before the forking, all of that content resides now at Wowpedia. Therefore, to avoid confusion and follow the community, throughout the remainder of this article, I will refer to Wowpedia rather than Wowwiki.

2Wikipedia contains more than 33,761,906 content pages and 4.6 million articles in 1100 portals (i.e., categories) to Wowpedia’s 122,993 content pages, including articles. In addition, Wikipedia has 22,482,949 registered users with 130,101 users having “performed an action” in the last 30 days. Wowpedia, on the other hand, currently has 83,389 registered users, while the number of users who have “performed an action” in the last 30 days is 188.

3Although many of the featured articles’ talk pages include more rapid exchanges of asynchronous talk (near synchronous, at times), by “at the same time” I also mean to include any collaboration over minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, and years because members of the community routinely come and go, visiting talk pages, picking up threads of discussion when noticed or of interest. That said, the nature of wiki collaborations is distinctly different than that with codices—due to the fact that articles are never considered final drafts. Discussions and associated article changes may occur over a matter of minutes or extend over months—whereas a codex was in the possession of one person at a time, and therefore, readers could not interact with other readers or, of course, the writer. And, as I have already noted, wiki collaboration involves the ability to edit texts and so differs from, for example, common classroom uses of peer collaboration that focus on readers giving individual writers feedback.

4A “Neutral Point of View” (often referred as NPOV) is a principle that describes an authoring or editing perspective representing views fairly and without bias (or at least attempting to remove as much bias as possible). On Wowpedia, an editor has to assume a neutral point of view when writing articles” (“Neutrality policy”).

5“UTC” refers Coordinated Universal Time, which is, according to Wikipedia, “the primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time. It is one of several closely related successors to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT)” (“Coordinated Universal Time”). In some cases, readers may notice missing timestamps; on Wowpedia contributors who do not sign their comments using four tildes (~~~~), which on MediaWiki automatically creates the signature and timestamp for a comment, may have manually typed in their username or an administrator has added the user’s name to the comment.

Works Cited

Barton, Matt. “The Future of Rational-Critical Debate in Online Public Spheres.” Computers and Composition 22.2 (2005): 177-90. Print.

---. “Is There a Wiki in This Class? Wikibooks and the Future of Higher Education.” Wiki Writing: Collaborative Learning in the College Classroom. Ed. Robert Cummings and Matt Barton. U of Michigan P, 2008. 178-94. Print.

“Be Bold in Updating Pages.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

Bolter, Jay David. Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2001. Print.

Brandt, Deborah. “At the Dawn of (Mass) Writing.” Conference on College Composition and Communication Convention. St. Louis, MO. March 2012. Presentation.

---. Literacy in American Lives. Cambridge UP, 2001. Print.

---. “Sponsors of Literacy.” College Composition and Communication 49.2 (1998): 165-85. Print. Bruffee, Kenneth. "Collaborative Learning." College English 46.7 (1984): 635-53. Print.

---. Collaborative Learning: Higher Education, Interdependence, and the Authority of Knowledge. Johns Hopkins UP, 1998. Print.

Cohen, Noam. “Care to Write Army Doctrine? With ID, Log On.” New York Times 13 Aug. 2009. Web. 1 Sep. 2014.

Cummings, Robert E. Lazy Virtues: Teaching Writing in the Age of Wikipedia. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 2009. Print.

Cummings, Robert E., and Matt Barton, eds. Wiki Writing: Collaborative Learning in the College Classroom. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2008. Print.

Davidson, Josh. “MilWiki Receives Army's Top Knowledge Management Honor.” Army.mil. 1 Sep. 2009. Web. 1 Sep. 2014

“Don't bite the newbies.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

Ede, Lisa, and Andrea Lunsford. “Audience Addressed/Audience Invoked: The Role of Audience in Composition Theory and Pedagogy.” College Composition and Communication 35.2 (1984): 155-71. Print.

“Edit Warring.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. n.d. Web. 1 Jun. 2014. Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy. MediaCommons P, 2011. Web. 30 Sep. 2011.

Garza, Susan Loudermilk, and Tommy Hern. “Using Wikis as Collaborative Writing Tools: Something Wiki This Way Comes—or Not!” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy 10.1 (2005). Web. 1 March 2010.

Gee, James Paul. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. New York: Routledge, 2010. Print.

---. “Literacy, Discourse, and Linguistics: Introduction.” Journal of Education 171.1 (1989): 5-17. Print.

Gere, Anne Ruggles, and Robert D. Abbott. “Talking About Writing: The Language of Writing Groups.” Research in the Teaching of English 19.4 (1985): 362-85. Print.

Gibson, James J. “The Theory of Affordances.” Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology. Eds. Robert Shaw and John Bransford. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1977: 67-82. Print.

Hunter, Rik. “Erasing ‘Property Lines’: A Collaborative Notion of Authorship and Textual Ownership on a Fan Wiki.” Computers and Composition 28.1 (2011): 40-56. Print.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York UP, 2006. Print.

---. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge, 1992. Print.

Jenkins, Henry, Katie Clinton, Ravi Purushotma, Alice Robison, and Margaret Weigel. “Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century.” The MacArthur Series on Digital Media and Learning, 2006. Web. 1 Jan. 2007.

Johns, Ann M. Text, Role, and Context: Developing Academic Literacies. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.

Johnson, Robert R. “Audience-Involved: Toward a Participatory Model of Writing.” Computers and Composition 14.3 (1997): 361-76. Print.

Knobel, Michele, and Colin Lankshear. A New Literacies Sampler. New York: Peter Lang, 2007. Print. Kroll, Barry. “Writing for Readers: Three Perspectives on Audience.” College Composition and Communication 35.2 (1984): 172-185. Print.

Leuf, Bo, and Ward Cunningham. The Wiki Way: Quick Collaboration on the Web. Boston: Addison- Wesley Professional, 2001. Print.

Lundin, Rebecca Wilson. “Teaching with Wikis: Toward a Networked Pedagogy.” Computers and Composition 25.4 (2008): 432-48. Print.

Lunsford, Andrea, and Lisa Ede. “Among the Audience.” Engaging Audience: Writing in an Age of New Literacies. Eds. Elizabeth Weiser, Brian Fehler, and Angela Gonzalez. National Council of Teachers of English, 2009. 42-70. Print.

“Neutrality policy.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

Nystrand, Martin M. “A Social-Interactive Model of Writing.” Written Communication 6.1 (1989): 66-85. Print.

Nystrand, Martin M., and Deborah Brandt. “Response to Writing as a Context for Learning to Write.” Writing and Response: Theory, Practice, and Research. Ed. Chris Anson. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English, 1989. 209-28. Print.

Nystrand, Martin M., and Margaret Himley. “Written Text as Social Interaction.” Theory Into Practice 23.3 (1984): 198-207. Print.

Nystrand, Martin M., Stuart Greene, and Jeffrey Wiemelt. “Where Did Composition Studies Come From? An Intellectual History.” Written Communication 10.3 (1993): 267-333. Print.

Porter, James E. Audience and Rhetoric: An Archaeological Composition of the Discourse Community. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1992. Print.

Purdy, James. “When the Tenets of Composition Go Public: A Study of Writing of Wikipedia.” College Composition and Communication 61.2 (2009): W351-W373. Web. 1 Dec. 2009.

Sanger, Larry. “The Early History of Nupedia and Wikipedia: A Memoir.” Open Sources 2.0. Eds. Chris DiBona, Mark Stone, and Danese Cooper. Sebastopol: O'Reilly Media, 2005. 307-38. Web. 13 March 2008.

Spigelman, Candace. Across Property Lines: Textual Ownership in Writing Groups. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2000. Print. Studies in Writing and Rhetoric Series.

---. “Habits of Mind: Historical Configurations of Textual Ownership in Peer Writing Groups.” College Composition and Communication 49.2 (1998): 234-55. Print.

“Statistics.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. n.d. Web. 16 Sep. 2014. “Statistics.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 16 Sep. 2014. Swales, John. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Boston: Cambridge UP, 1990. Print.

“Talk: Aegywnn.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

“Talk: Deathwing.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

“Talk: Illidan Stormrage.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

“Talk: Lich King.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

“Talk: Medivh.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

“Talk: Sylvanas Windrunner.” Wowpedia: The Free World of Warcraft Encyclopedia. Curse, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

Thompson, Clive. “The Future of Reading in a Digital World.” Wired. Condé Nast. 22 May 2009. Web.

22 May 2009.

“Transmedia Storytelling.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2014.

Vie, Stephanie, and Jennifer deWinter. “Disrupting Intellectual Property: Collaboration and Resistance in Wikis.” Wiki Writing: Collaborative Learning in the College Classroom. Eds. Robert Cummings and Matt Barton. U of Michigan P, 2008. 110-23. Print.

U.S. Army, Department of Defense. “Wikified Army Field Guide.” Open Government Initiative. The White House. Web. 2 November 2014.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. “Made Not Only in Words: Composition in a New Key.” College Composition and Communication 56.2 (2004): 297-328. Print.