Composing Literary Arguments in an 11th Grade International Baccalaureate Classroom: How Classroom Instructional Conversations Shape Modes of Participation

by George E. Newell, Theresa Siemer Thanos, and Matt Seymour

Abstract

In U.S. secondary schools there is an overriding emphasis on formulaic approaches to argumentative writing instruction in English language arts that tends to trivialize disciplinary norms of argument and evidence because of institutional pressure to bolster students’ test performances. This paper seeks to provide an ethnographically-informed framework for understanding for whom, how, when, and to what extent it is possible for students to participate, through writing, in the study of literature as the central disciplinary content of English language arts. The corpus of data used in this study of an 11th grade International Baccalaureate (IB) classroom (26 students) consisted of classroom instruction (video-recordings and field notes) that occurred across an initial instructional unit (September 8th to November 3rd). Of particular importance is a summative writing assignment, teacher interviews and collaborative data analysis (with video clips), student interviews about instruction and their writing, samples of student writing, and related documents. We also analyzed two essays written by the two case study students in response to a writing assignment that the teacher, described as an IB “literary commentary with an unspecified topic” that she reframed as a literary argument. Discourse analysis of a series of events within instructional conversations revealed that rather than prescribed forms, the teacher offered “possible” writerly moves for her students’ arguing to learn. Consequently, her students enacted their writerly moves in a variety of patterns suggestive of disciplinary ways of knowing in English language arts rather than in a pre-set formula that they had learned in previous grades. In order to trace how the students enacted modes of participation (procedural display and deep participation) in disciplinary activity (literary argumentation) as writing practices and shifting writer identities we also conducted a multi-phased and multi-layered analysis using procedures based off of previous intertextual analysis scholarship and backward mapping processes. |

Keywords: literary argumentation, US English language arts classroom, community of practice

Contents

Two Students, Two Modes of Participation: Learning to Write a Literary Argument

The research reported in this article was funded, in part, by a grant from the US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, through Grant 305A100786 The Ohio State University (Dr. George Newell, principal investigator). We gratefully acknowledge support from the Center for Video Ethnography and Discourse Analysis and the Department of Teaching and Learning both at The Ohio State University, College of Education and Human Ecology. The opinions expressed within this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent views of the Institute of Education Sciences, the US Department of Education, or The Ohio State University.

“Academic Literacies” sees reading and writing as practices that are shaped by ideologies, identities, and institutional power relations that may either afford or constrain students’ participation in disciplinary knowledge (Lea and Street 156-57). For example, in US secondary schools, because of an emphasis on supporting students’ test performances shaped historically by autonomous notions of reading and writing, there is an overriding emphasis on formulaic approaches to argumentative writing instruction in English language arts. The ideology of the autonomous model for teaching and learning argumentation and argumentative writing tends to trivialize disciplinary norms of argument and evidence (Applebee and Langer), ignore the experiences and knowledge of adolescent writers, and focus attention on objectifiable text features and structures (Prior and Olinger). When arguments are reduced to forms where students are asked to drop content into pre-determined slots, it is no wonder that scholars such as Todd DeStigter have questioned the usefulness of the large presence of argument in the US secondary English curriculum. However, when teachers embrace a more dialogic view of argumentation, they leverage the unique social experiences and practices within a particular context as “keys to understanding the human condition and the social, cultural, and political conditions of people’s lives” (Bloome, Newell, Hirvela, and Lin1).

This article is an effort to provide an ethnographically informed framework for understanding for whom, how, when, and to what extent it is possible for students to participate, through argumentative writing, in the study of literature as the central disciplinary content of English language arts. Although Mary Lea and Brian Street and other scholars often reference “participation as learning,” we explore this construct in some detail by examining how differing modes of participation (Prior) evolve out of differing opportunities. We also (re)frame the teaching and learning of argumentation and argumentative writing as a social practice, always embedded in socially constructed epistemological principles rather than a technical and neutral skill (Street).

The Context for the Study

The ethnographic and discourse analytic case study reported here was part of an eight-year, US Institute of Education Sciences (IES) funded research project on teaching and learning of literature-related argumentative writing in high school English language arts classrooms. We have collaborated with 61 classroom teachers in urban and suburban schools in central Ohio in the US Midwest. Among the array of approaches that we observed over the eight-year period were alternatives to traditional approaches; however, we are now looking with particular concern for what students are learning to do in and through writing in these classrooms that include writing practices for addressing a range of purposes and audiences. Arthur Applebee and Judith Langer offered a challenge to teachers “to provide students with a rich understanding of the rhetorical context implicit in such writing, and of strategies for addressing such tasks effectively without reducing them to a formula” (181). In turn, we have challenged ourselves to study how, when, and under what circumstances this is possible in teaching argumentative writing that allows for flexibility and choice in what students write and how they write it.

We note that argumentative writing is not monolithic and that even though people might use the same term—argumentative writing—they are not necessarily referring to the same thing. Simply stated, teachers and students might define argumentative writing as the taking of a position and advocating for that position competitively through argumentation (warrants, evidence, counter arguments, etc.). Alternatively, teachers and students might define argumentative writing as the exploration, learning, and advancement of an idea not in competition with others but in cooperation and dialogue with others who might have begun with a different perspective. Understanding that engaging in argumentative writing is pluralistic has implications for how the teaching and learning of argumentative writing might be framed as social practices.

As an extension and further exploration of previous studies of teaching and learning argumentative writing as social practice in English language arts classrooms—described in George Newell, David Bloome, and Alan Hirvela’s Teaching and Learning Argumentative Writing in High School English Language Arts Classrooms—this article considers how students in a high school International Baccalaureate (IB) Literature classroom learned to write by participating in a particular “community of practice” (Lave and Wenger). The purpose of this study is to explore an IB teacher’s instructional approach for teaching literature-related argumentative writing, an approach that did not specify a particular form or formula that students needed to use. Instead, the teacher’s instructional conversations and instructional activities helped students learn to make the moves—ways of taking action—that constitute literary argumentation (VanDerHeide).

Our project was directed by two questions: (1) What were the key events of an instructional unit during which students’ modes of participation were made manifest through intertextual tracings? (2) How were the students’ modes of participation revealed in and fostered by speaking and in writing when making literary arguments as revealed through intertextual tracings?

Theoretical Framework

In contrast with the dominant “skills” view, we have adopted an “ideological” view of literacy, in which literacy not only varies with social context and with cultural norms and discourses (regarding, for instance, identity, gender, and belief)—what might be termed a “social” model—but also that its uses and meanings are always embedded in relations of power. It is in this sense, we suggest, that literacy in general and teaching and learning argumentative writing in particular can be seen as ideological: they always involve contests over meanings, definitions, boundaries, and control of the literacy agenda. For these reasons, it becomes harder to justify teaching only one particular form of literacy when the learners already will have been exposed to a variety of everyday literacy practices (Lea and Street).

We also take a situated, emic view of what counts as “good writing,” grounded in theories of writing as social practice within a broader theoretical framework of social constructionism in which languaging and languaging relations are central to how people act and react to each other (cf., Bloome, Carter, Christian, Otto, and Shuart-Faris; Gergen; Newell, Bloome and Hirvela). In our view, rather than formulas and recipes, what fosters “good writing” in a classroom is interactionally constructed during instructional conversations in which the teacher and students are acting and reacting to each other as well as to the content and form of the written texts. Following the work of David Bloome, Stephanie Power Carter, Beth Morton Christian, Sheila Otto, and Nora Shuart-Faris, Discourse; Roz Ivanič; Paul Prior; and Brian Street, we view writing as languaging knowledge and learning embedded in particular social events with all of the complex social and cultural processes involved in human relationships.

Many of the classrooms we studied using ethnographic methods and perspectives over eight years took up an “argumentation as learning” perspective to the teaching of literature. Argumentation as learning within English language arts asks students to consider complex and multiple definitions of knowledge and ways of knowing and to recognize that insights into an understanding of the human condition and their own lives are continuously evolving (Bloome, Newell, Hirvela, and Lin). This framework is grounded in the idea that knowledge is discursively constructed over time and that discourse processes, social actions, and communicative practices shape what counts as knowing and doing within a particular group (Gergen; Prior).

Accordingly, arguing to learn can be seen as the ability to participate more effectively in written genres of a wider range of communities of practice (Applebee). One way to conceptualize this social action through language is with the term “writerly move,” or action mediated through language (Harris; Bazerman). Grounded in Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger’s view of learning as participation, Prior has described two modes of participation (in a graduate school context) as “procedural display” and “deep participation.” These modes “involve ascending levels of access to and engagement in disciplinary activity” (Prior 100) such as learning how to make a literary argument in a high-level IB English high school classroom. An important implication for understanding “learning to write” is to avoid relying on single idealized pathways or trajectories of expertise. Instead, we embrace what Prior has pointed out from Lave and Wenger that “forms of participation in communities of practice are diverse, multiple, always peripheral, and that there is no core to such communities” (102). This idea shapes the general argument that we are making about learning to write within a social constructionist framework.

Methods

Design of the Argumentative Writing Project Study

Teachers were recruited to the study based on recommendations of school district administrators and teachers associated with the local National Writing Project affiliate. Our project was designed as follows: each academic year, seven to thirteen teachers were recruited to participate in the project; the summer before each academic year, the teachers participated in a three-week summer workshop on the teaching of argumentative writing. The content of the summer workshops was based on the concept of argumentative writing as inquiry and learning (cf., Newell, Bloome, and Hirvela). The workshop consisted of discussions of academic articles and sections of George Hillock’s Teaching Argument Writing and the writing of arguments by the teachers in response to essays and exercises (such as the “slip or trip” exercise in which readers must examine a picture for clues as to whether a murder suspect is lying and then write a “report” to the police chief warranting their claims). During the last week of the workshop, teachers individually developed curricular and instructional plans for teaching argumentative writing. Although teachers shared ideas with each other, no attempt was made to standardize their instructional plans or how they conceptualized argumentative writing as inquiry and learning. At the end of the workshop, members of the project met with each teacher to discuss research procedures for the upcoming year.

A member of our project was assigned as the lead researcher for each classroom to conduct an ethnographic and discourse analytic case study of the teaching of argumentative writing across the ensuing year. During the academic year, we observed and video-recorded an average of at least two class sessions per week (depending on what was happening in the classroom, observations and video recordings might be conducted every day for a few weeks, while at other times not for a few weeks). We also conducted teacher and student interviews, collected classroom documents and student work, and debriefed with the teachers frequently. Monthly meetings were held with the teachers for them to share their experiences teaching argumentative writing with each other.

Research Site and Participants

The study took place in the 2014-2015 academic year (the data presented later is from the autumn 2014 semester). The site of the research study and the source of our data for this article was an 11th-grade IB English classroom located in an academic magnet school in a major urban school district in the state of Ohio in the US. The school has a reputation for academic excellence and various options for participation in both Advanced Placement (AP) and IB programs across a range of content areas. Please note that the constraints of The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board only allow us to use pseudonyms for all references to the teacher and the students. The teacher, Ms. Hill, self-identified as African American, female, and having twelve years of English language arts teaching experience at the time of the study. She had taught IB English for three years. At the time of the study, Ms. Hill had just begun a master’s degree in English education. At that time, the class was composed of 22 students who self-identified as white (16), African American (2), Somalian American (2), Latina (1), and Asian American (1). The majority of the students also were enrolled in other AP and IB courses. According to school policy, Ms. Hill and her students would work together for two years, 11th grade and 12th grade.

Case Study Students

Out of the students who agreed to be regularly interviewed, Ms. Hill chose four focal students whom she believed represented different kinds of experience with and knowledge of writing literary arguments. For purposes of this study, we selected only two students: Gary (white, male), who was one of the stronger readers and writers in the class and was a frequent contributor to whole-class discussions, and Catherine (white, female), who often contributed to class discussions but struggled with reading and writing. She revealed to us that she felt “a bit intimidated” by some of her peers in the IB classroom. However, she said she wanted to use the school year with Ms. Hill to learn how to be a better writer and to get a high-level IB diploma.

Our selection of Gary and Catherine as case studies was purposeful in that we were especially interested in developing “telling cases” of deep participation and procedural display (Lea and Street, Prior, respectively). To be clear, we are not proposing these two modes as a classification of “good” or “poor” writers. Although the two modes—deep participation and procedural display—are a limited heuristic, we think they capture important patterns of school-based disciplinary socialization that Lea and Street treat as necessary but not sufficient. Rather than treating disciplinary practices and genres as relatively stable and as unproblematic for students to reproduce once learned, academic literacies enabled us to understand Gary’s and Catherine’s argumentative writing practices “as more complex, dynamic, nuanced, situated, and involving both epistemological issues and social processes including power relations among people and institutions, and social identities” (Lea and Street 228). Specifically, we examined Gary’s and Catherine’s argumentative writing practices by considering when, how and what adaptations they made.

The 11th grade IB English class was embedded in a “humanities” program, an advanced or “high level” IB option students could self-select for the study of literary analysis. The course description on the IB website states:

The course is organized into three areas of exploration and seven central concepts, and focuses on the study of literary works. Together, the three areas of exploration of the course add up to a comprehensive exploration of literature from a variety of cultures, literary forms and periods. Students learn to appreciate the artistry of literature, and develop the ability to reflect critically on their reading, presenting literary analysis powerfully through both oral and written communication. (Retrieved from http://www.ibo.org/)

We include this quote not only to highlight the academic demands of the course, but also to point out that Ms. Hill took the course description seriously, as the criteria implied in the quote above were reinforced by an IB assessment regimen consisting of “two essay papers, one requiring the analysis of a passage of unseen literary text [literary argument], and the other a response to a question based on the works studied” as well as “a written assignment based on the works studied in translation, and [performance] of two oral activities presenting their analysis of works read.” This testing regimen shaped a great deal of Ms. Hill’s instructional conversations with students. However, rather than separating test preparation from her concerns with engaging her students in new argumentative writing practices, before an IB test she took limited time to review and practice the format. She also used the testing regimen to teach students to be reflective about their reading and writing performances (using rubrics across the school year) within the larger institutional context of the IB testing program that included a range of oral (e.g., “formal oral commentary and interview”) and written assessments (e.g., “literary commentary”). As background, it is important to note that two years earlier, the students’ ninth grade English language arts course was their entry into formal, academic writing. Ms. Hill described the writing instruction in the ninth grade as an “introduction to the five-paragraph theme” and “a kind of academic boot camp to tear you down to build you back-up as a student” (interview, 18 Sept. 2014). In other words, Ms. Hill challenged her students’ notions of what counted as good argumentative writing, including practices that had been sanctioned within the school context, and engaged them in discussion of and practice in arguing to learn while also embedding various requirements of the IB assessment within their discussions and writing.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

Following Street as well as David Bloome, Judy Klaman, and Matt Seymour, as ethnographic researchers our approach to data collection and analysis is to hover just above classroom events; that is, we observe events in their immediate contexts. It is in the events that teachers and students employ a range of practices that privilege some discourses and as well as some students over others. In this section, we describe our approach to data collection and analysis as a part and parcel of a logic of inquiry guided by these assumptions.

Because class sessions occurred two days (Monday and Thursday) per week each for 80 minutes, we were able to video record almost every class session. The teacher focused her instruction during the autumn semester on writing arguments in response to literary texts: a set of Hemingway short stories and Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid. After reviewing the data collected from Ms. Hill’s classroom and in collaboration with her, we identified two key classroom events to analyze. Event 1 occurred an hour into the class session on October 30th, when Ms. Hill distributed what she labeled “Paragraph A” and “Paragraph B,” two essays that students in the class had written in response to Hemingway’s short story, “Up in Michigan.” Event 2 entailed a small group discussion of a thematic analysis that considered connections between “Indian Camp” (Hemingway) and Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid. During this event, one of the case study students, Gary, proposed a broader archetypal framework for interpreting literature, a topic he took-up in his literary argument, while Catherine struggled with what she regarded as a “totally new way to write.” With Ms. Hill, we understood these classroom events as key because during these events Ms. Hill and her students engaged in instructional conversations that explicitly explained criteria for “good” argumentative writing (event 1) and for supporting students’ own topic selection for writing a literary argument (event 2).

The corpus of data used in this study consisted of classroom instruction (video recordings and field notes) that occurred across an initial instructional unit (September 8 to November 3) that concluded with a summative writing assignment, teacher interviews, and collaborative data analysis (with video clips); student interviews about instruction and their writing; samples of student writing; and related documents. For this article, we also analyzed two essays written by the two case study students—Catherine and Gary—in response to what Ms. Hill described as an IB “literary commentary with an unspecified topic” that she reframed, through dialogic interaction with her students, as a literary argument.

In order to respond to our first research question regarding analysis of key events in the instructional unit, the theoretical framework for the procedures used in data collection and data analysis derive from Bloome, Power Carter, Christian, Otto, and Shuart-Faris and are labelled microethnographic discourse analysis. Throughout data collection, researchers, in collaboration with the teacher, asked what are the key events in the classroom that need to be explored in depth in order to better understand the teaching and learning of argumentative writing (Mitchell 238-41). A key event is defined here as a classroom event that is viewed by participants as crucial for students’ acquisition of those social practices that define them as engaging in writing a “literary argument,” that is, a literature-related argument. We need to note that the acquisition of a social practice involves both its situated enactment (the procedures that count as doing that social practice in social situations) and the social and cultural ideologies that provide a social practice with its meaningfulness (cf., Bloome, Carter, Christian, Otto, and Shuart-Faris). A key event may be recurrent, such as a series of instructional conversations on what counts as “literary argument,” or it may be a single occurrence of an event (as per Mitchell’s telling case).

After identifying key events in the classroom, we analyzed video recordings of those key events using procedures described in Bloome, Carter, Christian, Otto, and Shuart-Faris. In brief, the event was transcribed and an utterance-by-utterance analysis conducted of how the teacher and students acted and reacted to each other and constructed meaning and conceptions of argumentative writing. In order to capture how a key event was situated within the flow of classroom activity and learning, classroom lessons both before and after a key event were also analyzed. We also looked for analogous classroom events before and after the targeted key event in order to understand how a social practice (such as using argumentative moves to teach literary argument) evolved over time. As part of the analysis of each key event, we interviewed the teacher and students about the event, how it fit into the broader context of classroom activity, and how they interpreted the meaningfulness of what occurred in the key event.

To respond to our second research question regarding students’ modes of participation, case study students’ written products were examined for evidence of the influence of key events through intertextual tracings (Olsen, VanDerHeide, Goff, and Dunn). We also interviewed students about their writing. We asked students to read their writing aloud and then describe how they composed it. Our goals in these interviews were (a) to understand how each student conceived of the writing task; (b) to trace features of previous instructional conversations; and (c) to find connections to their sources (primary and secondary sources).

In order to trace how students’ enacted modes of participation in writing practices and shifting writer identities, we began our analysis with the students’ final essays. We conducted a multi-phased and multi-layered analysis using procedures (based on previous intertextual analysis scholarship and backward mapping processes suggested by Green and Wallat; Prior; Olsen, VanDerHeide, Goff, and Dunn). First, we constructed a data set of transcribed classroom interactions, curricular materials, and writing from within the instructional unit. Second, we analyzed each essay for connections to the texts and talk over time, marking the traced connections. Third, we used “text-based” interviews in which the students described their writing process; we analyzed these interviews for connections to the essays as well as personal background that were not accessible from the essay (the product) itself (Prior). The tracings among the essays and other texts, and modes, illustrate the actions the students took to participate in the writing practices of the classroom community.

Before describing how we interpreted and understood Ms. Hill’s approach to teaching literature-related argumentative writing and how her students responded, it is worth recalling that we are particularly interested in Streets’ academic literacies model and related work (e.g., Bloome, Carter, Christian, Otto, and Shuart-Faris; Lewis, Enciso and Moje) whose learning theories foreground power, identity, and agency in the role of language in learning processes. Specifically, we are concerned with how Ms. Hill re-locates authority in two classroom events. That is, rather than assuming that the authority for what counts as a “good” argument resides in her own pre-set criteria or in the demands of the IB writing assessments, she and her students socially construct what makes sense through and within instructional conversations. Of course, such a shift is not easy or simple, and, as will become obvious, Ms. Hill and her students engage in moments of tension.

Instructional Context

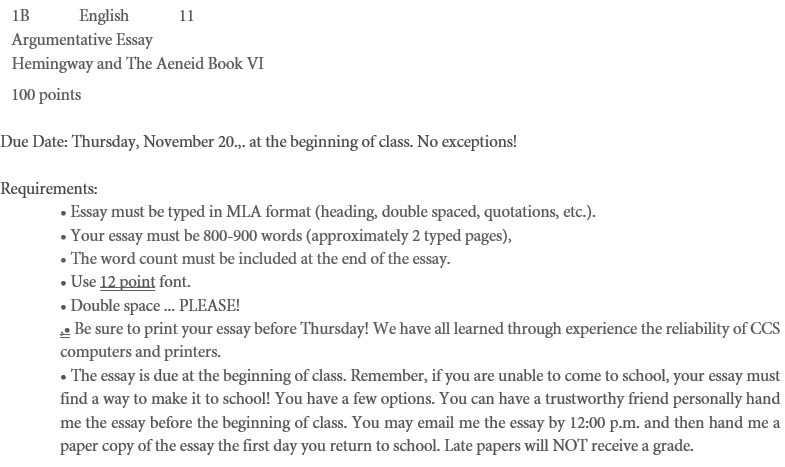

Over the course of the semester from August 28 to November 20, Ms. Hill spent some portion of each of 14 sessions teaching her students both the Toulmin model of argumentation and how to write “an essay on some aspect of Hemingway’s short stories, Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid or a comparison of the two” (See Fig. 1 below.) A key feature of this assignment is the absence of a particular topic or question to consider. In an interview, Ms. Hill reported that the reason for this decision was to introduce her students to the nature of the IB’s assessment of literary commentary: “They [the students] have to choose the topic. The teacher is supposed to be pretty hands-off. And that is part of the struggle. And there are [IB] rules where I am able to read it [essay] but not comment on the paper or able to make very specific comments” (interview, 13 Oct. 2014).

Fig. 1. The writing assignment.

Another feature of the assignment was the absence of any prescription for essay structure. For Ms. Hill, early efforts to teach argumentative writing during autumn 2014 focused on form and then by late October began to shift toward using argumentation as means of developing original ideas rather than adhering to a pre-set form. Ms. Hill’s experience during the 2014 summer workshop shifted her approach to writing instruction away from a focus on structural concerns to a concern for ideational issues as she decided to move her students from argumentative writing with a pre-set format (five-paragraph essay) to a more dynamic consideration of format including claim, evidence, warrants, and counterarguments for literary arguments. Put another way, Ms. Hill began to shift toward arguing-as-learning, but this move inserted an element of risk on the part of both her students and herself as their teacher. Perhaps the clearest example of this shift is how Ms. Hill employed certain writing samples during instructional conversations and activities to entextualize (Bauman and Briggs) her notions of literary argument. We noted that Ms. Hill entextualized literary argument on at least three different occasions (October 23, October 30, and November 3) and in doing so demonstrated the importance of generating, developing, and elaborating on evidence using warrants.

However, this shift presented a significant challenge for her and her students, as she had to strike a delicate balance between teaching the form of the writing and the content of the writing. To accommodate IB demands that students develop their own content, Ms. Hill’s approach to the first argumentative writing assignment (literary argument) was to do several lessons on argumentative terms such as claim, evidence, and warrant. To accommodate her concerns about her students’ reliance on the pre-set form of the five-paragraph essay, she did not discuss form. When her students asked about the organization she expected to see in their essays, she reminded them of the single format that they had learned in ninth grade and in tenth grade and suggested that now it was time to try “new forms that weren’t so structured and [to] focus on your ideas.” As we describe, in event 1 and event 2 she also relied on students’ ideas and students’ writing samples as sources for considering a range of ideas and formats for literature-related argumentative writing.

Event 1: Small Group Discussion of Archetypes in Literature

During the session of October 23, Ms. Hill asked her students “to try out an idea” by reading a handout titled “Katabasis: The Journey to Hell and Back: The Descent Motif” that included a general description of descent myths in antiquity and then listed seven “characteristic elements of the Journey to Hell or Katabasis (literally ‘descent’).” Ms. Hill then proposed the idea of analyzing literature by comparing how two or more texts might share a motif, a symbol, etc. She then asked the students, “Do you buy this idea or is it too much of stretch?” Ms. Hill invites her students to critique the motif by asking them to consider how far they are willing to “stretch” its sense-making value. After a brief exchange in which the students expressed conflicting points, she asked them to read through the first two paragraphs of “Indian Camp” and the episode in Book VI of The Aeneid in which the Sibyl guides Aeneas to his father’s spirit. In She then initiated the following brief discussion as a prelude to small group discussion:

Ms. Hill: Do you see any connections here?

Student 1: Both have boats.

Students: (laughter)

Student 2: In both stories they cross rivers… geographical barriers are crossed.

Student 3: The Indians are like the Sibyl that guide a character and ferry across a river.

Ms. Hill: Okay. How many of you think the comparison is too much?

Student 1: Sometimes a river is just a river.

Ms. Hill: Yes. Sometimes a river is just a river. Let’s consider if it is possible to make such a comparison. Get into your [assigned] groups and discuss if you feel, “no way,” or “maybe” and then jot down an example.

Small Group Discussion

In advance of this event, Ms. Hill had agreed to place four case-study students—Gary, Catherine, Raed, and Angela—in a small group so that we could focus our analysis on how students were participating in both whole-class and small-group discussions. Moving between these two participant structures allowed us to trace how various students were participating in learning how to write a literary argument. The small group work lasted about 13 minutes, during which the students compared the two texts for similar imagery, symbols, and themes. Gary, one of the group members, also made the argument that, while the comparison is possible, it is not because the motifs in these two stories are shared or that one author influenced another author but because there are archetypes in all literature. He commented that,

I think there are connections between Hemingway’s “Indian Camp” and Virgil’s Aeneid but it is a connection of archetype between all creativity and not just these two stories. And if you look hard enough, you can find anything if you look hard enough. Those [Dora the Explorer and other examples from popular culture] are some of the examples that I found.

With five minutes left for the small-group discussion, Ms. Hill moved into their circle, and asked, “How is it going?” Raed reported that the group had made the comparison she had requested, and then Gary commented, “You know, the story [“Indian Camp”] has the archetype of the journey across a river but it was not inspired by The Aeneid.” Ms. Hill asked him to explain. The following exchange unfolded.

Gary: We were talking about how literature in general has archetypes [makes a circling motion with his hands].

Ms. Hill: Are you talking about real connections or something silly?

Gary: Okay. We did the comparison you wanted us to do. [Gary shows Ms. Hill a page from his notebook with a list of points of comparison the group developed. Raed briefly summarizes the group’s list.]

Raed: In “Indian Camp” Nick learns from his father and in The Aeneid, Aeneas learns from his father about his future. They are both learning from their fathers.

Ms. Hill: Okay.

Gary: We have come to a consensus … a mutual consensus …

Ms. Hill: Wait a minute. Everyone agrees with Gary?

Raed: [Shrugs his shoulders and smiles.]

Gary: We agreed …

Ms. Hill: Really?

Students: (laughter)

Gary: We think that the comparison is there but the authors did not make the connections explicitly. They were inspired by archetypes. [inaudible]

Ms. Hill: Give me an example.

Gary: In “Dora [the Explorer],” she constantly has to cross a river. [inaudible] I think there are archetypes that inspire all writers…

Students: (laughter)

Raed: [With a smile] He’s convincing. I’m convinced.

A close look at this exchange shows a subtle conversational move that Ms. Hill makes to shift the authority from herself to the discussion, to a stance of “power with.” For example, she asks for evidence for Gary’s claim: “Give me an example.” Authority for reasonableness of an evidence- and warrant-based claim is located not in her authority per se but as a moment in the flow of the argument Gary is making. This approach continued during the whole class discussion when Ms. Hill asked all of the students to consider Gary’s ideas regarding the centrality of archetypes in literature. This shift in the location of authority in both the small group and in the whole class from a person or persons to the dialogic interaction is key to moving from a stance of arguing for one’s claim (i.e., traditionally defined argumentation) to a stance of dialogic consideration in which the power for constructing meaning, is a “power with” rather than a “power over” (cf.,Bloome, Carter, Christian, Otto, and Shuart-Faris; Noddings ).

Event 2: Entextualizing Sample Essays: Toward an Integration of Form and Content

About an hour into class session eight—one week after event 1—Ms. Hill distributed two writing samples that she had labeled “Paragraph A” and “Paragraph B” (See below.) She entextualized (Newell, Bloome, Kim, and Goff) these samples by first excerpting and retyping two of her students’ essays written in response to Hemingway short stories during the summer and then bringing them into an instructional conversation about the significance of evidence and backing in literary argument. Ms. Hill excerpted the samples from her students’ required summer reading and writing assignments rather than from their work during the autumn 2014 semester. The use of “sample” essays from the summer reading/writing assignments to entextualize that for which she wanted her students to be held accountable was quite intentional.

Paragraph A

The theme of innocence is portrayed by the character Liz in the short story, Up in Michigan, by Ernest Hemingway. The thoughts and actions of Liz helps the reader to better understand the nature of innocence within the story. For example, Liz feels funny about the fact that she likes the color of Jim’s hair above the tan line. This funny feeling represents a lack of maturity in Liz because if she can’t handle looking at Jim’s arms, how will she be able to handle a physical relationship with him? So, Liz’s reaction to seeing Jim’s arms, represents an innocence that she had with men. Liz’s innocence is revealed again when she expects something to happen between her and Jim when he returns from the hunting trip. “Liz hadn’t known when Jim got back but she was sure it be something. Nothing had happened. The men were just home, that was all.” Nothing could possibly happen between Jim and Liz if the two never held a conversation. This situation proves that Liz has optimism in a futile situation. This means that Liz hopes for something that she does not put any work into, while at the same time, allowing the reader to yet again realize that she presents a sense of innocents when dealing with men. Therefore, the character, Liz reinforces the theme of innocents in the story Up in Michigan by Ernest Hemingway.

During an interview, Ms. Hill pointed out that rather than selecting the “perfect paper,” she wanted to “begin to make them [students] see the bigger picture—claim and evidence and the analysis. They always want to do this picking on words and mistakes someone made in the writing rather than paying attention to the ideas and the analysis.” In the instructional conversation below, after a student reads Paragraph A aloud, Ms. Hill asks for overall impressions of the paragraph.

Ms. Hill: What did you guys think of this, just overall? Yes.

Student 1: There was lack of ideas … Like they were partial but not necessarily completed.

Ms. Hill: What kind of … are you talking about … ?

Student 1: Sorry …

Ms. Hill: So, the evidence you think?

Student 1: Yeah. Evidence.

Ms. Hill: I think the evidence there is good, but maybe another piece [of evidence] would be better. Hanna.

Hanna: Explanation of the analyzing or arguing is not as thorough as it could be.

Ms. Hill: Okay. Huh. Are you talking about the warrants and the backing?

Hanna: Yeah.

Ms. Hill: Alright. Anybody else? Ok, Amy.

Amy: I think the explanations are made kinda informally. It just doesn’t sound as formal as …

Ms. Hill: So just the word choice, right?

Amy: Like the sentence structure.

Ms. Hill: (Shaking her head.) The sentence structure. So, yes. Uhm. Anything else? Margie?

Margie: I thought that some of the sentences weren’t (inaudible), and that …. And rephrase it and make it, like, useful.

Ms. Hill: Uhm. Were some ideas like repeated? Is that what you are telling me?

Margie: Yeah. Okay. So, with this paragraph, really everything that you guys have said is something that I have mentioned. Right? Now, I do think… that we need to give a little bit more credit to the explanation of the evidence.

Ms. Hill: Okay. So. One of the things you guys have said, I actually … And you know that this paper is actually somebody’s paragraph in the room, right?

In this segment of the instructional conversation, Ms. Hill focuses the students on two issues: (1) how the sample demonstrates a well-developed approach to constructing a literary argument with evidence and warranting; and (2) since the sample was composed by a classmate—a point she had made clear before distributing the sample—that their remarks should “give a little bit more credit” to the writer’s efforts. Simultaneously, she languages what constitutes effective use of warranted evidence (“to give a little bit more credit to the explanation of the evidence”) as well as the need to treat one’s peers with sensitivity and understanding (“you know that this paper is actually somebody’s paragraph in the room, right?”). We think this illustrates the use of a writing sample both to teach literary argument and to language relations to build a community of writers willing to support one another’s writing efforts.

Later in the same instructional conversation, Ms. Hill introduced a second sample (Paragraph B below) to consider another feature of the literary argument: the claim or thesis statement.

Paragraph B

In “Father and Sons,” a short story by Ernest Hemingway, a theme of escape and return is prominent. The theme is illustrated through the subject of Nick's relationship with his father, a relationship that is described in two different ways. The first way is described through childhood experiences that Nick remembers sharing with his Father, whereas the second is through Nick’s reflections as a grown man. As an adolescent, Nick often went to the woods behind the Indian camp to escape from his father. He also tried to escape his father's conservative values by having sex with Trudy. But children generally need their parents and almost always return home. Even though Nick could temporarily escape his father, he always returned to the tense relationship. During the story, Nick recalled one of his more hateful memories of his father; when Nick came home from fishing without it and said he lost it, he was whipped for lying. Afterwards he had sat inside the woodshed with the door open, his shotgun loaded and cocked, looking across at his father sitting on the screen porch reading the paper, and thought, 'I can blow him to hell. I can kill him.' Finally, he felt his anger go out of him and he felt a little sick about it being the gun that his father had given him. Then he had gone to the Indian camp, walking there in the dark.

During this segment of the instructional conversation, Ms. Hill shifts the focus to what she believes is a complex claim. Her students’ response to the sample suggests that they are surprised that the claim does not include the three-point structure they had learned in ninth and tenth grade.

Ms. Hill: One thing that I want to say about this. You remember “Fathers and Sons,” right? Uhm. One thing that the writer did very well. I think this would be difficult to write. Because you have Nick as an adult and then Nick as a child. And how do you organize that? Do you know what I mean? So, I thought the student did a great job of that I think that sentence there where it says. Uhm, Let’s see. (Reads from sample:) “The theme is illustrated through the subject of Nick’s relationship with his father, a relationship that is described in two different ways.” Do you see how the writer lets the reader know that we are going to talk about two different things here? That was good I thought. So, what did you think of the claim?

Sandy: If you are referring to the first sentence, it is kinda short but it does mention the theme.

Max: Like last year it [claim] had to have three points. This has just one idea.

Sandy: I am wondering what you want us to do with the claim. Can we say it our own way?

Ms. Hill: Okay. When we are talking about the claim, we are talking about what is the writer trying to prove, right? One thing that I told Mario is that … remember freshman year when [the teacher] used to say “Your thesis needs to be one sentence. The thesis must be one sentence with title, author and assertion or it’s wrong,” right? And be done. We have to teach you format somehow. Otherwise, you will be all over the place when you are trying to write your [literary] argument for IB. So, if you can state your claim in the first sentence or two then you are okay. Are you okay with that?

When Ms. Hill asks, “So, what did you think of the claim?”, an interesting interaction emerges that suggests the students’ legacy of writing instruction requiring formulaic claims (“Like last year it [claim] had to have three points”) that the students had encountered in ninth and tenth grade. In a debriefing session, Ms. Hill discussed this moment: “My comments were probably confusing because I pointed out what was good about the claim. But then I realized that the claim may not work in writing a literary argument for the IB assessment.” Of significance here is Ms. Hill’s emphasis on working through the criteria for what counts as a good claim within the discussion, embracing tensions that are present because of students’ past writing experiences. Ms. Hill stresses a genuine openness to her students’ ideas and opinions as they analyze their own writing practices.

The evolution in the instructional conversation above from a focus on style and structure to ideas reveals how Ms. Hill is implicitly defining a good literary argument, at least in that classroom event. At a theoretical level, what the analysis of the instructional conversation shows is that it is not in the selection of the writing sample per se that teachers communicate what counts as good writing but rather in the languaging and language relations in which the writing sample is analyzed. Analysis of the instructional conversation also shows that although Ms. Hill attempted to bring the students into a dialogue about the ideas and later the claim in the writing sample, she was unable to do so—at least not during this event. The students focused on style aspects.

Amy: I think the explanations are made kinda informally. It just doesn’t sound as formal as ….

Ms. Hill: So just the word choice, right?

Amy: Like the sentence structure.

Ms. Hill: (Shaking her head.) The sentence structure.

In order to focus on ideas as a key criterion in defining a high-quality literary argument, a criterion reflective of her newly adopted view of argument as exploration and learning, Ms. Hill had to shift to authoritative languaging and languaging relations that allowed her to be explicit about what focus should be taken in assessing a literary argument. She also re-positioned students so that they were aligned with the stance she took. These moves seem necessary in light of her concerns for how the students might perform on the IB assessment that was “always on [her] mind.”

In summary, Ms. Hill’s use of entextualization brings contextual influences together in conversation. That is, as she took students through the challenge of breaking away from a structural focus (the five-paragraph essay) and toward an ideational focus through argumentation, Ms. Hill not only adhered to the academic discipline of literary studies and the constraints of the IB examinations but prioritized social interaction as part and parcel of how and what she is teaching. In doing so, she worked with her students to build relationships that led to support for one another as they work to craft literary arguments. In the next section, we will consider how Gary and Catherine took up Ms. Hill’s efforts to break from a preset essay format.

In this section we respond to our second research questions by describing the process of two case-study students participating in the classroom context described above. Note that before beginning our analyses we acquired the students’ permission to include their writing as well as the content of the interviews we conducted with them. Specifically, we consider the students’ shared experiences as well as writing moments in which we see each of their modes of participation diverge. For each student, we provide an illustration of how one excerpt from each of their essays traces across events, talk, and interactions, and we provide an extended depiction of each student writer, as made manifest across data: their interviews, written work, verbal participation (or lack thereof) in full class conversations and with their peer writing partner, assignment sheets, and the teacher's interview and informal conversations.

Both Catherine and Gary willingly applied themselves to the challenges of the IB English curriculum but with differing levels of confidence. Gary believed he would do well in IB because he “enjoyed the challenge of new ideas,” while Catherine described herself as “a bit nervous about all of the reading and smart students [in the classroom].” We chose to focus on Gary and Catherine because they approached the writing assignment with very different modes of participation: procedural display and deep participation (Prior). Recall that we are less interested in a single idealized pathway or trajectory of expertise. Rather we include Gary’s and Catherine’s efforts to write a literary argument each as a telling case of participation in communities of practice that are diverse, multiple, always peripheral, and without a single (or simple) core to be reached at the end of an instructional unit, a semester, or a school year (Prior).

Catherine: Participation as Procedural Display

After weeks of preparation, part of which we describe above, Ms. Hill gave the students just over a week to write their literary arguments. Catherine explained to us that she “waited till the last minute to get started and then had to work fast.” She had done so because “last [school] year I learned to write a five-paragraph essay and I got good grade [in English language arts] because I knew it. So, I did not take a lot of time. . . . I wait[ed] until the last minute [to write the essay] and then realized how difficult it was [to compare two different stories from differing historical periods and places].” This may explain, in part, why Catherine participated procedurally to display “all the parts of a good essay.” (see Table 1 for an illustration of Catherine’s mode of participation.)

Essay Except |

Originating Event/Text |

Type of tracing |

How tracing used |

Affordance of the trace |

Mode of Participation |

Literature often portrays how a culture deals with certain archetypes. Although “Snows of Kilimanjaro” by Hemingway probably was not based on The Aeneid, they are both written about the same general subjects. The Aeneid was written in 29-19 BCE in Rome, Northern Italy, and possibly Greece. It was based on ancient Roman culture, while Hemingway writes of the same topics from the view of a well-traveled American in the 1930s. The Aeneid and “Snows of Kilimanjaro” both portray the writer’s own cultural belief surrounding death, regret and hell. |

Class Session 10 (10/23/14) Small group work: Reference to opening sentence: “Literature often portrays how a culture deal with certain archetypes.” Interview T-Chart practice from 6th grade |

Thematic |

Repeating |

Catherine relied on writing practices she participated in during previous school years that she assumed that Ms. Hill required: (1) form first with five paragraphs and a three-part thesis statement; (2) prioritize performance for a grade: “I’m not sure what [Ms. Hill] wants me to write." |

Catherine’s participation during the unit was shaped by her concern with form over content: she reported, “not really knowing what I mean but I know she [teacher] wanted us to make some sort of comparison.” This is procedural display. She also admitted to “waiting until the last minute [to write the essay] and then realizing how difficult it was [to compare two different stories from differing historical periods and places].”

|

Table 1: Illustration of Catherine’s Mode of Participation

One feature of the writing assignment that confused and frustrated Catherine was that Ms. Hill did not offer a specific question or prompt, though Catherine knew what texts she wanted to write about. When we asked how she composed her essay, she traced the practice back to sixth grade: “I made a T-chart with the titles at the top (“Snows of Kilimanjaro” in one column and The Aeneid in the other). This is something I learned to do in sixth grade. Then I thought about three ideas for each story. They (teachers) made us develop three ideas in freshman year (ninth grade) —I think Ms. Hill wanted us to do that too.” Based on her success with writing in ninth and tenth grade, she assumed that Ms. Hill “would want to see three ideas.” When Ms. Hill gave the students time to work in pairs to develop ideas, Catherine wrote the following at the top of her notes: “The Aeneid and The Snows of Kilimanjaro both have themes involving regrets, death and hell.” The list of notes that Catherine sketched suggests that she is listing ideas but not developing an argument.

Catherine’s essay included four paragraphs with a total of 872 words—within the limit of 800-900 words prescribed by the assignment. In general, Catherine’s essay introduces her focus on the two literary narratives and concludes the first paragraph (below) with what she described as a “thesis statement”: “The Aeneid and “Snows of Kilimanjaro” both portray the writer’s own cultural belief surrounding death, regret, and hell.”

Literature often portrays how a culture deals with certain archetypes. Although “Snows of Kilimanjaro” by Hemingway probably was not based on The Aeneid, they are both written about the same general subjects. The Aeneid was written in 29-19 BCE in Rome, Northern Italy, and possibly Greece. It was based on ancient Roman culture, while Hemingway writes of the same topics from the view of a well-traveled American in the 1930s. The Aeneid and “Snows of Kilimanjaro” both portray the writer’s own cultural belief surrounding death, regret and hell.

Catherine’s participation during the unit was shaped by her concern with form over content: she reported, “I know she [teacher] wanted us to make some sort of comparison.” We regard this as an instance of procedural display. We use Prior’s extension of David Bloome, Pamela Puro, and Erine Theordrou’s notion of procedural display from “doing a lesson” to “literacy events” that involve talking and text. Catherine’s interpretation and enactment of the writing assignment was procedural in that she decided to use a format (five-paragraph essay) to present three themes—a practice that she had learned in previous school years that Ms. Hill’s approach was attempting to change. Prior, in reference to Lave and Wegner’s terms, might describe Catherine’s practices as “relatively sequestered from participation” as Ms. Hill defined the goals of IB English.

In addition, rather than an argument or an analysis, Catherine’s essay repeats, in summary fashion, ideas that she accumulated across the instructional unit. During an interview, Catherine stated that she was “frustrated with [Ms. Hill] as I don’t know what I have to do to get a good grade.” Put another way, when we traced Catherine’s sources back to the instructional conversations (See event 1 and event 2 above), it was clear that the moves she made, that is, her participation, made it quite difficult to approximate the kind of literary argument that Ms. Hill had in mind: “When I read [Catherine’s] essay, it was a rather simple five-paragraph theme, and I did not understand if she was making an argument. She seemed to write an essay like she would’ve in ninth or tenth grade. I want her to get beyond using the same form all of the time” (interview, 6 Dec. 2014).

In summary, although Ms. Hill approached literary argumentation as an exploration of ideas and experiences that emerged out of reading and discussing literary texts, Catherine relied on a pre-set formula that she assumed would lead to a “good” grade. We employ Catherine’s case to stress that students need time to understand and appropriate the complexities of argumentation as a way of writing about and knowing literature. In English language arts classrooms in the US, argumentative writing is often taught in a single instructional unit (Newell, Bloome, et al.); however, Catherine’s case illustrates why argumentative practices (in writing and discussion) are more likely to be appropriated across an entire academic year or longer. We also believe that Ms. Hill’s approach to literary argumentation (as described above) early in the academic year illustrates the value and challenges of pedagogical moves that proffer and support students’ writing practices that push against formulaic and pre-set structures. Of significance (but not presented in this article) was Ms. Hill’s responsivity to students’ evolving argumentative writing practices over the course of the academic year that included one-on-one conferencing with her students to provide individualized feedback as well as challenges to their conception of what counts as good argumentative writing.

Gary: Deep Participation

Prior defines “deep participation” as not only “open[ing] paths toward full participation, that is, taking up some mature role in a community of practice, but also increase[ing] opportunities to assume privileged roles in a community. Deep participation may be displayed in the roles a person assumes, in her relations to other participants, and qualitative aspects of her engagement in practices” (103). For instance, Gary chose to write on a topic quite different from his peers, relying not only on content from instructional conversation led by Ms. Hill, but “ideas I got from a class that I took in ninth grade.” He developed his ideas for his essay from “Carl Jung 's theory . . . that all humans share basic ideas of archetypes.” However, we traced his developing ideas from event 2 during the small group discussion of a thematic analysis that considered connections between “Indian Camp” and Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid (See Table 2).

As we discussed above, during a small-group discussion, Gary positioned himself as a kind of expert in archetypal analysis, especially when challenged by Ms. Hill to explain his claim that, “[w]e think that the comparison is there but the authors did not make the connections explicitly. They were inspired by archetypes.” We considered this as an instance of relatively “deep participation” in the IB English classroom community of practice not by assuming that he has a contribution to make the field of literary studies (cf., Hamilton’s examination of Frye’s criticism) but by recognizing how Gary has positioned himself relative to his peers and how he engages in discussion with them and with Ms. Hill.

Essay Excerpt |

Originating Event/Text |

Type of tracing |

How tracing used |

Affordance of the trace |

Mode of Participation |

Carl Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist who founded analytical psychology. Throughout his work he introduced and developed the ideas of the collective unconscious and archetypes. He states that “This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes . . . “Carl Jung's theory states that all humans share basic ideas of archetypes. Jungian Archetypes are underlying forms that appear as images and motifs. They include ideas such as the mother, child, and the elder to name a few popular ones. All in all, the theory states simply that all humans share basic ideas and images that connect us. |

Class Session 10 (10/23/14) Small group work: Interview |

Thematic |

Responding |

For Gary’s first draft, he developed an introduction by relying on his response to Ms. Hill question’s that asked Gary (during small group activity) to explain why he thinks an archetypal analysis is more valid that a comparison of two texts. Gary was not concerned with a certain form for his essay as Ms. Hill has encouraged them to find new forms. Gary also generated many intertextual connections to make his argument by alluding to both other Hemingway short stories that he read outside of class and to narratives and characters from popular cultural such as “Dora, the Explorer.” |

With his initial draft, Gary positions himself as something of an expert (relative to his peers) in that he deliberately frames his argument using Jungian notions of archetypes as thematic analysis across two texts. However, in doing so he moves beyond comparison of two text to argue that all literary texts include archetypes. |

According to Carl Jung' s theory of the collective unconscious, Ernest Hemingway writes his short stories with such archetypes in mind as to appeal to his readers. This is found to be true when examining writing or screenplay of other time periods and finding the same archetypes in each. These archetypes allow readers and viewers to connect to what they are viewing. |

Interview |

Thematic |

Responding and Extending |

Gary and Ms. Hill both pointed to this statement as the essay’s general claim. He continues to write in response to Ms. Hill’s questions about an archetypal analysis. He introduces notion of “screenplay” to extend the archetypal to popular culture. |

|

Gary’s Essay |

Originating Event/Text |

Type of tracing |

How tracing used |

Affordance of the trace |

Mode of Participation |

“This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes . . . “Carl Jung's theory states that all humans share basic ideas of archetypes.

|

Conference with Ms. Hill |

Thematic |

Responding |

Gary’s introduction removes general references to Carl Jung and begins with a direct quote. |

With his second draft, Gary’s participation shifts to procedural display after he realizes he will lose points for going beyond word length, being too general with his evidence, and, including works from popular culture that Ms. Hill does not approve of. |

Table 2: Illustration of Gary’s mode of participation.

The first paragraph of Gary’s literary argument includes what he described as “a framework for the analysis that I want to do:”

Carl Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist who founded analytical psychology. Throughout his work he introduced and developed the ideas of the collective unconscious and archetypes. He states that, “This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes . . .” Carl Jung 's theory states that all humans share basic ideas of archetypes. Jungian Archetypes are underlying forms that appear as images and motifs. They include ideas such as the mother, child, and the elder to name a few popular ones. All in all, the theory states simply that all humans share basic ideas and images that connect us.

Rather than considering one or two pieces of literature, as Ms. Hill had recommended when she made the writing assignment, Gary assumed that he would make a much broader claim (italicized) that he states at the end of his introductory paragraph:

According to Carl Jung' s theory of the collective unconscious, Ernest Hemingway writes his short stories with such archetypes in mind as to appeal to his readers. This is found to be true when examining writing or screenplay of other time periods and finding the same archetypes in each. These archetypes allow readers and viewers to connect to what they are viewing.

Using interview data and observational field notes, we traced the content and argumentative moves of Gary’s introduction directly to both event 1 and event 2, which we describe above. During event 1, Gary noticed that, “she [Ms. Hill] gave a choice in how to write our papers . . . I like this so that I can try something new and less boring.” Within event 2, Gary took advantage of his small group discussion as an opportunity to try out his ideas about “Carl Jung' s theory of the collective unconscious” first with his three peers and then with Ms. Hill when she entered the small group to monitor progress.

Despite the fact that we describe Gary’s participation as “deep,” Ms. Hill was not convinced that Gary’s writing was successful, especially his first draft, which not only exceeded the word limit (1064 words) but from her perspective “he included ideas and references to literature (a list of Hemingway short stories and a children’s television program, “Dora, the Explorer”) that seemed irrelevant to me. He also—you can see my written feedback—was way too general and lost focus.” These are the things Ms. Hill said to Gary when they had met for a writing conference after he had composed an initial draft. In a second draft, Gary’s participation shifted more to procedural display after he realized he would lose points for going beyond word length, being too general with his evidence, and including works from popular culture of which Ms. Hill did not approve as appropriate given the demands of IB writing assessment.

Conclusions

For too long, the teaching of English language arts and written composition in US secondary schools has been dominated by an ideology of literacy with a narrow notion of what counts as legitimate uses of written language and of how written language might be understood and interpreted. Street’s critiques of school literacy are more specific in that he points to an autonomous model of literacy that has provided deficit models that alienate and exclude particular populations of students. However, our work with Ms. Hill and her students offers an alternative ideology grounded in a conceptualization of literacy in general and argumentation and argumentative writing in particular as social. Teachers like Ms. Hill create a classroom climate open to diverse perspectives, and with their students they “fashion” (Bloome, Kalman, and Seymour) literacy practices that students value as part and parcel of their personal, social, and cultural lives both in and out of schooling. Yet, as we have tried to demonstrate here, this way of teaching and learning is complicated by the diverse experiences, ideologies, and histories of both teacher and students.

We began with the question, “how does a teacher’s approach to instructional conversations and instructional activities shape students’ modes of participation in learning how to compose a literary argument in a high-level IB English classroom?” As the study progressed, however, rather than offering a description of a single approach, our study considered what became shifts in the teacher’s epistemology—sometimes emerging spontaneously during instructional conversations. Our analyses also reveal how diverse influences, especially the teacher’s beliefs and understandings of argumentation, were involved in how the teacher and students interactionally constructed processes of entextualization (extracting bits of text from the writing sample) and recontextualization (adapting the bit of writing extracted from writing samples to the texts students were writing). To be specific, a key finding is that it is not just the writing sample per se but how that sample is taken up in the instructional conversation that becomes central to what counts as good argumentative writing and, in turn, what counts is shaped by the teacher’s epistemological beliefs.

Perhaps one of the more obvious ways to make this case is to point out that Ms. Hill, the teacher whose classroom we observed during the autumn 2014 semester, took several weeks to teach literature-related argumentative writing. And this fostered a complex and dynamic process of assessing not just texts but students’ growth and understanding as writers. Our first implication is that the process of entextualization is not a matter of simply directing students to use (or avoid) text structures to improve their writing but creating new understandings about argumentative writing and about the social practice of sharing ideas. As Raed, one of the case study students in Ms. Hill’s classroom commented during an interview, “I can see that [Ms. Hill] wants us to see what is on everybody’s mind.”

“Test prep” and getting an “A” are perpetual concerns in English language arts classrooms, and to an extent these concerns were present in Ms. Hill’s IB English classroom. Such a discourse that includes not only specific forms for writing but also an autonomous ideology may undercut the benefits of teaching and learning extended, complex written literary argumentation (Applebee and Langer). How then is change possible? Our second implication is that entextualization may also provide a powerful means for engaging students in shifting their modes of participation from procedural display to deep participation, possibly offering English language arts teachers an alternative discourse for talking about assessment and about what counts as good writing. In Ms. Hill’s classroom, we observed instructional conversations not only about “test prep” or how to ensure an “A” performance but also an emergence of a metalanguage about how various writers understand a multitude of ideas about good argumentative writing. But even more importantly, we observed a teacher and students complexify argumentation and literary understanding as they wondered about the content and form of sample essays. Entextualizing samples of good argumentative writing as part of instructional conversations seemed to create a metalanguage (Geoghegan, O’Neill, and Petersen) that enabled Ms. Hill to address her expectations about a particular writing assignment rather than introducing a decontextualized notion of “correct” form and/or content. This approach may be especially valuable to students such as Catherine who clearly want to learn new content and genres for writing about literature but found their repertoires and ranges of ideas rather limited to the five-paragraph theme (Johnson, Star, Thompson, Smagorinsky, and Fry).

A general finding from the discourse analysis of the literacy events is that rather than making the writerly moves for argumentation and analysis explicit and mandatory, Ms. Hill offered “possible” moves for her students’ arguing to learn. Consequently, her students enacted their writerly moves in a variety of patterns suggestive of disciplinary ways of knowing in English language arts rather than in a preset formula that they had learned in previous grade levels. Analysis of the writing also suggested their efforts to develop “provisional genres” (Dixon) to capture their tentative understandings of the stories they analyzed. This approach, Hillocks argues, is a deeply contested issue in English language arts (cf., “At Last”). At a theoretical level, what the analysis of the instructional conversations demonstrated is that the selection of the writing sample or an instructional activity per se is not the primary concern but the instructional conversation in which the writing sample or activity is used. In Ms. Hill’s instructional conversations, argumentation became dialogic inquiry (Newell, Bloome, and Hirvela) asking students to keep an open mind and allow claims to evolve as they engaged with others in dialogue and exploration of a topic, identification and examination of data, and consideration of alternative theses in seeking an understanding of the complexity of human lives as mirrored by literature.

Finally, deep participation in a community means something quite different in a high school IB contexts as compared to Prior’s studies of graduate school students. However, we think it is important to consider that students may participate in many different communities of practice differently across time—participation is a social construction that shifts according to the social situation in which participants may interact with one another. For future studies, we think this framework offers a new set of possibilities for a rich and robust understanding of writing development over time in a range of social and cultural contexts, some in school and some out of school.

Works Cited

Applebee, Arthur N. “Alternative Models of Writing Development.” Perspectives on Writing: Research, Theory, and Practice, edited by Roselmina Indrisano and James R. Squire, Routledge, 2000, pp. 90-110.

Applebee, Arthur N., and Judith A. Langer. Writing Instruction That Works: Proven Methods for Middle and High School Classrooms. Teachers College Press, 2013.

Bauman, Richard, and Charles L. Briggs. “Poetics and Performances as Critical Perspectives on Language and Social Life.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 19, 1990, pp. 59-88.

Bazerman, Charles. “Speech Acts, Genres, and Activity Systems: How Texts Organize Activity and People.” What Writing Does and How It Does It: An Introduction to Analyzing Texts and Textual Practices, edited by Charles Bazerman and Paul Prior, Routledge, 2003, pp. 309-39.

Bloome, David, George Newell, Alan R. Hirvela, and Tzu-ing Lin. Dialogic Literary Argumentation in High School Language Arts Classrooms: A Social Perspective for Teaching, Learning, and Reading Literature. Routledge, 2020.

Bloome, David, Stephanie Power Carter, Beth Morton Christian, Sheila Otto, and Nora Shuart-Faris. Discourse Analysis and The Study of Classroom Language and Literacy Events: A Microethnographic Perspective. Routledge, 2004.

Bloome, David, Judy Kalman, and Matt Seymour. “Fashioning Literacy as Social.” Re-theorizing Literacy Practices: Complex Social and Cultural Contexts, edited by David Bloome, Maria Lucia Castanheira, Constant Leung, and Jennifer Rowsell,Routledge, 2019, pp. 15-29.

Bloome, David, Pamela Puro, and Erine Theodorou. “Procedural Display and Classroom Lessons.” Curriculum Inquiry, vol. 19, no. 3, 1989, pp. 265-91.

DeStigter, Todd. “On the Ascendance of Argument: A Critique of the Assumptions of Academe's Dominant Form.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 50, no. 1,2015, pp. 11-34.

Dixon, John. “The Question of Genres.” The Place of Genre in Learning: Current Debates, Deakin U, 1987, pp. 9-21.

Geoghegan, Deborah, Shirley O’Neill, and Shauna Petersen. “Metalanguage: The ‘Teacher Talk’ of Explicit Literacy Teaching in Practice.” Improving Schools, vol. 16, no. 2, 2013, pp. 119-29.

Gergen, Kenneth J. An Invitation to Social Construction. Sage, 1999.

Green, Judith L., and Cynthia Wallat. “Mapping Instructional Conversations: A Sociolinguistic Ethnography.” Ethnography and Language in Educational Settings, vol. 5, 1981, pp. 161-95.

Harris, Joseph. Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts. Utah State UP, 2006.

Hemingway, Ernest. “Indian Camp.” The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway. Simon and Shuster, 2002, pp. 65-70.

---. “Up in Michigan.” The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway. Simon and Shuster, 2002, pp 59-62.

Hillocks, George, Jr. “At Last: The Focus on Form vs. Content in Teaching Writing.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 40, no. 2, 2005, pp. 238-48.

---. Teaching Argument Writing, Grades 6-12: Supporting Claims with Relevant Evidence and Clear Reasoning. Heinemann, 2011.

International Baccalaureate (n.d.) “About the IB's Programmes,” https://www.ibo.org/programmes/diploma-programme/curriculum/language-and-literature/language-a-literature-slhl/. Accessed 18 Dec. 2020.

Ivanič, Roz. “Discourses of Writing and Learning to Write.” Language and Education, vol. 18, no. 3, 2004, pp. 220-45.

Johnson, Tara Star, Leigh Thompson, Peter Smagorinsky, and Pamela G. Fry. “Learning to Teach the Five-Paragraph Theme.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 38, no. 2, 2003, pp. 136-76.

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. “Legitimate Peripheral Participation in Communities of Practice, Vol. 1” Supporting Lifelong Learning, edited by Roger Harrison, Fiona Reeve, Ann Hanson, and Julia Clarke, Routledge, 2002, pp. 111-126.

Lea, Mary R., and Brian V. Street. “Student Writing in Higher Education: An Academic Literacies Approach.” Studies in Higher Education, vol. 23, no. 2, 1998, pp. 157-72.

Lea, Mary R., and Brian V. Street. “The ‘Academic Literacies’ Model: Theory and Applications.” Theory into Practice, vol. 45, no. 4, 2006, pp. 368-77.

Lewis, Cynthia, Patricia E. Enciso, and Elizabeth Birr Moje, eds. Reframing Sociocultural Research on Literacy: Identity, Agency, and Power. Routledge, 2020.

Mitchell, J. Clyde. “Typicality and the Case Study.” Ethnographic Research: A Guide to General Conduct, edited by R. F. Ellen, Academic P, 1984, pp. 238-241.

Newell, George E., David Bloome, Min-Young Kim, and Brenton Goff. “Shifting Epistemologies During Instructional Conversations About ‘Good’ Argumentative Writing in a High School English Language Arts Classroom.” Reading and Writing, vol. 32, no. 6, 2019, pp. 1359-382.

Newell, George E., David Bloome, and Alan Hirvela. Teaching and Learning Argumentative Writing in High School English Language Arts Classrooms. Routledge, 2015.

Newell, George E., David Bloome, and the Argumentative Writing Project. “Teaching and Learning Literary Argumentation in High School English Language Arts Classrooms.” Adolescent Literacies: A Handbook of Practice-Based Research, edited by Kathleen A. Hinchman and Deborah A. Appleman, The Guilford P, 2017, pp. 379-97.

Noddings, Nel. The Challenge to Care in Schools: An Alternative Approach to Education.2nd ed., Teachers College P, 2005.